Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement

Engage for Equity Key Informant Survey

KEY FEATURES

COMMUNITY/ GEOGRAPHY

Academic/research partners

United States

LANGUAGE TRANSLATIONS

Spanish

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT OUTCOMES

Strengthened partnerships + alliances

Broad alignment

Diversity + inclusivity

Partnerships + opportunities

Acknowledgment, visibility, recognition

Mutual value

Shared power

Structural supports for community engagement

Expanded knowledge

New curricula, strategies, + tools

Improved health + health care programs + policies

Actionable, implemented, recognized solutions

PLACE(S) OF INSTRUMENT USE

Community/community-based organization

Academic/research institution/university

Hospital, clinic, or health system

Local government agency; federal government

PSYCHOMETRIC PROPERTIES

Construct validity

Content validity

Face validity

Factorial validity

Internal consistency reliability

YEAR OF USE/TIME FRAME

2016-2018

2009-2013

Assessment Instrument Overview

The Engage for Equity Key Informant Survey (KIS)1-9 has 97 questions for use by academic partners, mainly principal investigators (PIs) or project directors. It assesses project-level characteristics of a project or partnership and provides factual information on perceptions of community, academic, and other partners on processes and practices in their community-based participatory research (CBPR) and community-engaged research projects (CEnR), and their perceived intermediate and long-term outcomes. The KIS is part of a set of two instruments that also includes the Engage for Equity Community Engagement Survey (CES).

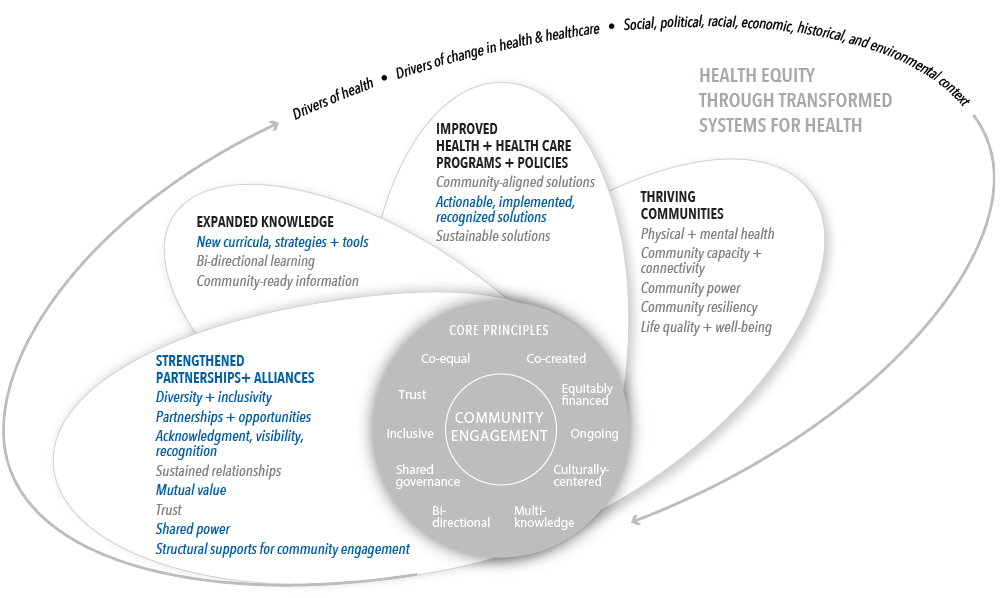

Alignment with Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement Conceptual Model

The questions from the KIS were aligned to the Assessing Community Engagement Conceptual Model. Figure 1 displays the alignment of the KIS with the Conceptual Model domain(s) and indicator(s). Where an instrument is mapped broadly with a domain or with a specific indicator, the figure shows the alignment in blue font.

Table 1 displays the alignment of Y-AP’s individual questions and validated focus areas with the Conceptual Model domain(s) and indicator(s). The table shows, from left to right, the aligned Conceptual Model domain(s) and indicator(s), the individual questions from the Y-AP transcribed as they appear in the instrument, and the validated focus area(s) presented in the article.

CONCEPTUAL MODEL DOMAIN(S) AND INDICATOR(S) | ASSESSMENT INSTRUMENT QUESTIONS | VALIDATED FOCUS AREA(S) |

STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Broad alignment with all indicators in this domain | Does this project have at least one community partner who might be interested in participating in a workshop focused on partnership self-evaluation? | General |

To what extent does your partnership engage in regular self-evaluation assessment, collective reflection, or quality improvement strategies? Does this partnership engage in annual self-evaluations or reflection? | Reflective practices | |

STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Diversity + inclusivity | In which language would you prefer to respond these questions? Does this project have community partners from the community of interest (e.g., patients or community members from affected communities) who have or will be engaged across multiple stages of its research processes?* | General |

Who initiated this study? Please describe who initiated this study. What types of community partners are involved in this project? Check all that apply. Please describe the other community partners involved in this project. For any in-person meetings, where are these in-person meetings held? On average, how many academic partners attend these in-person meetings? Please give a whole number value, even if it is approximate. On average, how many community partners attend these in-person meetings? Please give a whole number value, even if it is approximate. | Project features | |

How many people are currently core members of the community partnership (include members from all relevant agencies and independent community members)? Please give a whole number value, even if it is approximate. Over the course of this partnership, how many people, in total, have participated as community partners? Please give a whole number value, even if it is approximate. | Length and size of project and partnership | |

What social, economic, or structural issue most strongly impacts the health of the communities engaged in this project? | Community challenges | |

Does this project have community advisory board(s) or group(s) separate from the research partnership? Please give a whole number value, even if it is approximate. How many people, in total, are members of the community advisory group(s)? Please give a whole number value, even if it is approximate. | Advisory boards or groups | |

STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Partnerships + opportunities | Has this project had any trainings or formal discussions that focus on

| Training topics |

Have community partners received human subjects training? | Research integrity and governance practices | |

| STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Acknowledgment, visibility, recognition | Who approved participation in this research project on behalf of the community? Check all that apply. How important was it to the guidance and development of this project for it to receive approval from

| Research integrity and governance practices |

| STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Mutual value | Has this project had any trainings or formal discussions that focus on

| Training topics |

| STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Shared power | Does this project have community partners

| General |

Which partner (academic, community, or both) hires personnel on the project? Who decides how the financial resources are shared? Please describe who decides how financial resources are shared. Who decides how the in-kind resources are shared? Please describe who decides how in-kind resources are shared. Think of the overall budget and how project financial resources are divided among community partners and academic partners. Please enter the percentage of financial resources shared with community partners. | Hiring and resource sharing | |

How important was it to the guidance and development of this project for it to receive approval from

| Research integrity and governance practices | |

To what extent does or will the community advisory group(s) play the following roles?:

| Roles of advisory boards or groups | |

Do the formal agreements for the partnership include provisions or language about clear decision-making process (e.g., consensus vs. voting)?* | Formal agreements | |

STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Structural supports for community engagement | Is this project associated with a research consortium, network, or infrastructure (e.g., a practice-based research network (PBRN), a clinical trials network (CTN), a clinical and translational science award (CTSA), or another type of established research consortium) with a community engaged component? Does this research consortium have a community advisory board? | General |

| How would you describe this partnership? | Project features | |

To what extent do the bodies who approve the participation of the community in the research ensure the following?:

| Approvals | |

Does your partnership have written formal agreements such as a Memorandum of Agreement/Understanding or Tribal or Agency Resolution? Do the formal agreements for the partnership include provisions or language about

| Formal agreements | |

To what extent

| Institutional practices | |

EXPANDED KNOWLEDGE; New curricula, strategies + tools | Has this project developed any of its own evaluation instruments (formative, process, or outcome) or measures? | Project outcomes |

IMPROVED HEALTH + HEALTH CARE POLICIES + PROGRAMS; Actionable, implemented, recognized solutions | As a result of this partnership, have any IRB policies, procedures, or practices been developed or revised? Check all that apply. Were there other institutional policies or practices that were changed as a result of this study or partnership? Please describe the institutional policies or practices that were changed as a result of this study or partnership. | Project outcomes |

*Note that these questions are duplicated to reflect their alignment with multiple domains and/or indicators in the Conceptual Model.

Table 1 | Engage for Equity Key Informant Survey questions and alignment with the domain(s) and indicator(s) of the Assessing Community Engagement Conceptual Model

ASSESSMENT INSTRUMENT BACKGROUND

Context of instrument development/use

The articles discuss a range of academic-community collaborations and efforts across the United States that have focused on understanding “which partnering practices, under which contexts and conditions, contribute to research, community, and health equity outcomes.”3,9 Efforts were aimed at developing actionable knowledge that improves CBPR, CEnR, and participatory action research science. Efforts also focused on translating data to support equity and recognizing the struggles and gifts within the community.3 The articles discuss findings from three funding stages from the National Institutes of Health. Funding supported the development of the CBPR conceptual model, which contains four domains (context, equitable partnerships, research design/interventions, and outcomes). The model was refined through the development, testing, and implementation of two complementary assessment instruments – the KIS (described here) and the CES (described in another assessment instrument summary).2,3,9 The instruments are for use by academic and community partners to assess and understand their perceptions of the partnering process and outcomes.3

Instrument description/purpose

The KIS is completed mainly by the PIs or project director(s) of academic-community partnerships to describe project-level features. The 97 questions in the instrument assess the following 18 validated (i.e., construct, factorial) focus areas:

- Project features

- Length and size of project and partnership

- Type of study

- Populations and communities involved in project

- PI racial or ethnic groups

- PI population groups

- PI gender identity

- Community challenges

- Reflective practices

- Training topics

- Hiring and resource sharing

- Research integrity and governance practices

- Approvals

- Advisory boards or groups

- Roles of advisory boards or groups

- Formal agreements

- Institutional practices

- Project outcomes1,3,5,7

Studies have also used the KIS to explore the relationship between the type of final approval used in CEnR projects (e.g., no community approval, agency staff approval) with governance processes (e.g., control of resources and agreements), productivity measures, and perceived outcomes.1,6,8

KIS presents questions with open-ended, yes/no, various Likert scales, and “check the answers that apply” response options.

The KIS instrument in English and Spanish can be accessed here: https://engageforequity.org/tool_kit/surveys/key-informant-survey-introduction/.

Engagement involved in developing, implementing, or evaluating the assessment instrument

While the research that formed the foundation for the KIS took place over three funding stages, the entire research trajectory grew to be called “Engage for Equity”. Across these stages, academic and community collaborations took place between a range of partners including: Community-Campus Partnerships for Health, the National Indian Child Welfare Association, the Rand Corporation, the University of Waikato (New Zealand), the National Congress of Americans Indians (NCAI) Policy Research Center (PRC), the University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research (UNM-CPR), the University of Washington’s Indigenous Wellness Research Institute (UW-IWRI), and a think tank of academic and community CBPR experts.3,9 These partnerships supported the development, refinement, and pretesting of the KIS, including its “readability, length, content, sequence, and usability.”3

A shortened pragmatic version of the KIS and CES, called Partnership for Health Improvement and Research Equity (PHIRE), with 30 questions (also available in Spanish) was developed based on extensive statistical analyses and expert feedback from communities and academic partners. PHIRE represents the same focus areas as the longer instruments, with emphasis on a few core questions from the KIS and the CES. PHIRE has been piloted in multiple research, coalition, and engagement settings, and can be used for annual reflection and evaluation for partners who want to assess their strengths and areas to grow (please contact [email protected] to obtain use of the PHIRE).

Additional information on populations engaged in instrument use

Two sets of internet surveys were conducted in 2009 and 2015. The first set of surveys were included in the mixed-methods research project Research for Improved Health.3,8 PIs with research-focused funding and a minimum of two years of remaining in projects completed KIS. “Of these projects, 47 were located in Native communities (single or intertribal communities) and 153 were located in other communities (including 24 Hispanic, 21 multiple ethnicities, 20 African American, 7 Asian American, and 87 no specific ethnicity).”8 In 2009, the questions were refined and translated into Spanish.

In 2015, a total of 179 federally funded CBPR and CEnR projects of diverse populations across the United States participated in an analysis of KIS. Among the funded projects, 189 PIs (53% response rate) completed KIS. “Gift cards of $20.00 were sent as incentives in advance of participants receiving their KIS … Internet links.”3

Notes

- Potential limitations: Several articles in this summary referenced self-reported response bias and selection/sampling biases. The articles indicated that bias may have been introduced due to the fact that only projects identified as CBPR or CEnR in the federal RePORTER register were included. These results may not be applicable to other research projects with limited community engagement.1-3,5,7 The cross sectional analysis of internet survey and cases studies of only NIH-funded partnerships noted that the results do not support “causal/temporal inferences particularly as they relate to health improvement or reduced inequities.”2,5 Lastly, one article noted that considerations of survey length prevented thorough exploration of all aspects of structural governance.1

- Important findings: One article on the Engage for Equity effort noted “that the theoretical grounding and extant literature supports CEnR projects to engage in collective reflection to reap the full benefits of community engagement.” The effort supported understanding of the role of power within partnerships, including CBPR and CEnR projects. The Engage for Equity study design allowed for the opportunity to also conduct a randomized control trial of delivery of tools and resources developed in the effort through workshops or through the web, collect longitudinal data from 68 partnerships of the total sample, and analyze approaches to “building empowerment through collective-reflection” and action. The authors believe that “other tools and trainings, such as resources to help partnerships choose an equitable decision-making model or combatting racism, may be needed after partners identify areas of strength or concern.”3

Further analysis of the KIS among CEnR projects in Native communities found that involving tribal governments or health boards (TB/HG) resulted in “greater community control of resources, greater data ownership, greater authority on publishing, greater share of financial resources for the community partner, and an increased likelihood of developing or revising IRB policies.” The results provided evidence that supports the need for strong governance in communities (i.e., “regulation as the focus is on balancing the needs of protection of individuals from harm while trying to foster scientific innovation”), and stewardship over projects, benefit, and control over research. Strong governance could take place through “community-driven agreements, access to resources, and development or revision of IRB policies.”8

Analysis of the 2015 surveys of the KIS found that counter to principles of CBPR, where shared decision-making and co-administration of the research are expected, among funded CEnR projects examined, decisions tended to be made more by academic partners than community members. However, shared decision-making related to financial resources and hiring personnel did take place in approximately 30–40% of projects.1 Additionally, budget sharing between academic and community partners seemed relatively low for these kinds of collaborative projects (an average of 28.5% of projects), though higher for Native projects. “Approval on behalf of the community, community-based advisors as co-leadership, joint decision-making, and resource-sharing practices can help identify potential areas for partners to strengthen along their CBPR journey.”1

- Future research needed: Research exploring all aspects of structural governance is needed.1 Longitudinal study designs were also referenced as an area of further research.2

- Supplemental information: Additional analysis has been conducted using KIS on multiple kinds of partnerships, beyond the two internet survey sets in 2009 and 2015 (i.e., projects involving healthcare and government partners). The findings from the research, the most complete version of the KIS (see Dickson, 2020 below), and other information on the development and use of this instrument can be found in the following articles:

Oetzel, J. G., B. Boursaw, M. Magarati, E. Dickson, S. Sanchez-Youngman, L. Morales, S. Kastelic, M. M. Eder, and N. Wallerstein. 2022. Exploring theoretical mechanisms of community-engaged research: a multilevel cross-sectional national study of structural and relational practices in community-academic partnerships. International Journal for Equity in Health 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-022-01663-y.

Boursaw, B., J. G. Oetzel, E. Dickson, T. S. Thein, S. Sanchez-Youngman, J. Pena, M. Parker, M. Magarati, L. Littledeer, B. Duran, and N. Wallerstein. 2021. Scales of Practices and Outcomes for Community-Engaged Research. American Journal of Community Psychology 67(3-4):256-270. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12503.

Hanza, M., A. L. Reese, A. Abbenyi, C. Formea, J. W. Njeru, J. A. Nigon, S. J. Meiers, J. A. Weis, A. L. Sussman, B. Boursaw, N. B. Wallerstein, M. L. Wieland, and I. G. Sia. 2021. Outcomes of a Community-Based Participatory Research Partnership Self-Evaluation: The Rochester Healthy Community Partnership Experience. Progress in Community Health Partnerships 15(2):161-175. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2021.0019.

Dickson, E., M. Magarati, B. Boursaw, J. Oetzel, C. Devia, K. Ortiz, and N. Wallerstein. 2020. Characteristics and Practices Within Research Partnerships for Health and Social Equity. Nursing Research 69(1):51-61. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0000000000000399.

Duran, B., J. Oetzel, M. Magarati, M. Parker, C. Zhou, Y. Roubideaux, M. Muhammad, C. Pearson, L. Belone, S. H. Kastelic, and N. Wallerstein. 2019. Toward Health Equity: A National Study of Promising Practices in Community-Based Participatory Research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships 13(4):337-352. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2019.0067.

Reese, A. L., M. H. Marcelo, A. Abbenyi, C. Formea, S. J. Meiers, J. A. Nigon, A. Osman, M. Goodson, J. W. Njeru, B. Boursaw, E. Dickson, M. L. Wieland, I. G. Sia, and N. Wallerstein. 2019. The Development of a Collaborative Self-Evaluation Process for Community-Based Participatory Research Partnerships Using the Community-Based Participatory Research Conceptual Model and Other Adaptable Tools. Progress in Community Health Partnerships 13(3):225-235. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2019.0050.

Lucero, J., N. Wallerstein, B. Duran, M. Alegria, E. Greene-Moton, B. Israel, S. Kastelic, M. Magarati, J. Oetzel, C. Pearson, A. Schulz, M. Villegas, and E. R. White Hat. 2018. Development of a Mixed Methods Investigation of Process and Outcomes of Community-Based Participatory Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 12(1):55-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689816633309.

We want to hear from you!

Assessing community engagement involves the participation of many stakeholders. Click here to share feedback on these resources, or email [email protected] and include “measure engagement” in the subject line to learn more about the NAM’s Assessing Community Engagement project.

Related Products