Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement

Mature Partnership Indicators

KEY FEATURES

COMMUNITY/ GEOGRAPHY

Policymakers

Researchers

Ontario, Canada

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT OUTCOMES

Strengthened partnerships + alliances

Broad alignment

Partnerships + opportunities

Acknowledgment, visibility, recognition

Sustained relationships

Mutual value

Trust

Shared power

Structural supports for community engagement

Expanded knowledge

Broad alignment

PLACE(S) OF INSTRUMENT USE

Government agency

Academic/research institution/university

LANGUAGE TRANSLATIONS

Not specified

PSYCHOMETRIC PROPERTIES

Content validity

Face validity

YEAR OF USE

2000-2002

Assessment Instrument Overview

The Mature Partnership Indicators1,2 has 30 questions and is intended for use by policy makers and health researchers. It supports the management of collaborative knowledge generation and assesses the performance of a partnership, with focus on meeting information needs, level of rapport, and commitment to the partnership. The Mature Partnership Indicators is part of a set of three instruments that also includes the Common Partnership Indicators and the Early Partnership Indicators.

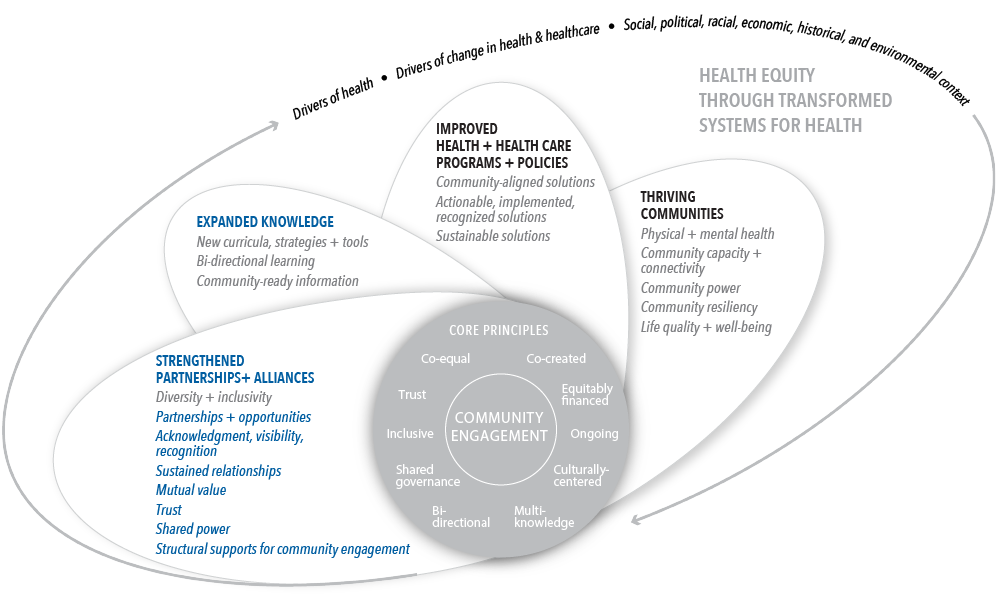

Alignment with Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement Conceptual Model

The questions in Mature Partnership Indicators were aligned to the Assessing Community Engagement Conceptual Model. Figure 1 displays the alignment of the Mature Partnership Indicators with the Conceptual Model domain(s) and indicator(s). Where an instrument is mapped broadly with a domain or with a specific indicator, the figure shows the alignment in blue font.

Table 1 displays the alignment of the Mature Partnership Indicators with the Conceptual Model domain(s) and indicator(s). The table shows, from left to right, the aligned Conceptual Model domain(s) and indicator(s) and the individual questions from the Mature Partnership Indicators transcribed as they appear in the instrument (with minor formatting changes for clarity).

| CONCEPTUAL MODEL DOMAIN(S) AND INDICATOR(S) | ASSESSMENT INSTRUMENT QUESTIONS |

STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Broad alignment with all indicators in this domain | 2.0 There is an increase in joint activity around the project |

STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Partnerships + opportunities | 7.0 Linkage with partner enhances partner linkage with community/other stakeholders 7.1 Linkage with partner does not detract from previously established linkages with other partners 3.1 Partners introduce each other to new networks |

| STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Acknowledgment, visibility, recognition | 3.1 Partners support each other publicly 3.0 Partners are perceived as experts in the research/ policy area and are referred to as such to others |

STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Sustained relationships | 1.3 Research purpose and objectives have been defined, documented, and referred to in an on-going fashion as the research progresses 1.1 More informal communication occurs, though formal meetings and communication continues 4.1 Partners provide advance notice of surprising or potentially contentious research findings or government decisions 1.2 Partners willingly provide ‘extras’, such as extra time or staff, to the project 2.2 On-going dialogue moves a research programme forward over a series of projects 3.2 Partners think of each other in relation to projects, committees, etc., outside of the research project relationship |

| STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Mutual value | 1.0 Partners are flexible about meeting partner’s changing needs and revising research plans and timelines 2.0 Partners understand the limits of each other’s flexibility 2.1 Appreciation is shown of each other’s efforts 5.0 Partners begin speaking a common language regarding research 6.0 Partners facilitate removal of barriers for each other’s work 1.0 There is joint commitment to the research project |

| STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Trust | 1.2 Roles and responsibilities have been defined up front 3.0 Partners understand research findings, their limits, and their implications for Ministry work 1.0 Conflict is dealt with openly, informally, and promptly 2.0 Trust has increased between partners 3.0 Comfort has increased between partners 4.0 Openness has increased between partners 6.1 Partners understand: *how things are communicated within the partner organization; *how senior level people work and what their concerns are; agendas, priorities, expectations, and limits; dissemination opportunities within the partner organization; opportunities for research use and impact within the partner organization; costs of monitoring, influencing, and incorporating research into decision-making |

| STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Shared power | 1.1 The partners contribute more resources, material and otherwise to the research project 2.1 Partners take on new roles with each other |

STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Structural supports for community engagement | 1.1 Project timelines and changes have been tracked through documentation 4.0 An informal or formal infrastructure exists for linking and transferring research between partners |

EXPANDED KNOWLEDGE; Broad alignment with all indicators in this domain | 4.1 The partnership’s work becomes integrated with work associated with other stakeholders |

Table 1 | Mature Partnership Indicators questions and alignment with the domains and indicators of the Assessing Community Engagement Conceptual Model

ASSESSMENT INSTRUMENT BACKGROUND

Context of instrument development/use

The article describes a study to “examine research receptor capacity and research utilization needs within the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (MOHLTC).” The study explored the “abilities of Ministry staff to find, understand and use evidence-based research in policy development processes.” The Health System-Linked Research Unit (HSLRU), which had experience engaging with Ministry partners and developing research directly intended for transfer into government decision-making, supported the development of instruments. The instruments reflect both processes and outcomes that can be used to “manage collaborative knowledge generation or assess the performance of a partnership between health researchers and policymakers.” The study led to the development of the Mature Partnership Indicators (discussed here), as well as the Early Partnership Indicators and the Common Partnership Indicators (discussed in other assessment instrument summaries), which use quantitative and qualitative approaches.2

Instrument description/purpose

The Mature Partnership Indicators instrument focuses on the three areas of:

- “Meeting information needs [including] partners are flexible about meeting partner’s changing needs and revising research plans and timelines; partners understand the limits of each other’s flexibility; [and] partners understand research findings, their limits and their implications for Ministry work”

- “Level of rapport [including] conflict is dealt with openly, informally, and promptly; trust…, comfort…, and openness has increased between partners; partners begin speaking a common language regarding research [and] facilitate removal of barriers for each other’s work; [and] linkage with partner enhances partner linkage with community/other stakeholders”

- “Commitment [including] joint commitment to the research project, an increase in joint activity around the project, partners are perceived as experts in the research/policy area and are referred to as such to others, [and] an informal or formal infrastructure exists for linking and transferring research between partners”

The Mature Partnership Indicators has 30 questions. The possible response options to the questions were not presented in the article.2

The Mature Partnership Indicators instrument can be accessed here: https://doi.org/10.1057/kmrp.2011.16.

Engagement involved in developing, implementing, or evaluating the assessment instrument

The Mature Partnership Indicators were developed using a cross-sectional survey followed next by qualitative interviews, which provided “detailed recommendations to improve access to research information, enhance use of the information once accessed, and promote an organizational culture supportive of research utilization.” Study participants involved in developing and validating the instruments included “all eight of Ontario’s HSLRUs, and their designated partners at the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care.” Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with eight Research Unit directors (or their designee) and their eight Ministry partners. Using the interview findings and findings from a literature review, the instruments were drafted and then tested with focus groups of HSLRU participants and one Ministry partner (the majority of whom were also participated in the interviews) to examine “clarity, feasibility, credibility, relevance, level of specificity, and their ability to support each evaluation question.”2

Additional information on populations engaged in instrument use

The study participants – HSLRU researchers and Ministry partners – conduct health research in a wide range of areas with policy implications, including “community health, cancer, dental health, rehabilitation, child health, arthritis, mental health, health information.” The partnerships often involved multiple projects, and included engagement with community, government, and research partners depending on the content area. Project activities were also wide-ranging and “included literature reviews, surveys, programme and service evaluation, costing estimates for policy initiatives, policy analysis, health system human resource analysis, intervention studies, knowledge dissemination to government and community, and knowledge transfer studies.”2

Notes

- Important findings:

- The Mature Partnership Indicators, as well as the Early Partnership Indicators and the Common Partnership Indicators (discussed in other assessment instrument summaries), support an improved understanding of knowledge translation partnerships, providing opportunities to measure success at each stage of partnership development. The authors maintain that the results of this study are applicable beyond the partners who tested the instruments, especially given the broad range of research content and type of research conducted by the study participants. Of note, a new partnership may be “unfairly judged if measured against, for example, the ideal standards of effective, informal communication channels that develop with more mature partnerships.”2

- The authors indicate that participants identified the Level of Rapport (one of the three dimensions in the Mature Partnership Indicators instrument) as a critical dimension of partnerships. It was “associated with a number of possible indicators revolving around conflict, trust, comfort, openness, and common language between partners. Rapport was also linked to the removal of barriers for each other’s work (e.g., easing the way for appropriate communication of research results).”2

- The article indicated that where partnerships were successful “participants reported an acknowledgement of each other’s needs, time lines, and limits of each other’s flexibility.” Participants also reported “mutual understanding of the implications of the research results for each other’s worlds.” Additionally, when considering the maturity of partnerships, the length of time working as partners may influence the characteristics displayed or exhibited among partners. In addition to the Common Partnership Indicators, Early Partnership Indicators, and Mature Partnership Indicators being used to evaluate relationships, they could also be used to monitor partnership processes and guide a set of deliverables that could be included in negotiated agreements.2

- Future research needed: “A future prospective pilot study could help generate evidence on the applicability of the tool in practice. Other future studies using these indicators might focus on prioritizing them, determining optimal frequency of measurement, usefulness in modifying the partnership midway through the partnership, or determining the extent to which they predict the use of research by policymakers. Alternatively, one might study which indicators are better suited for partnerships with bureaucrats, and which are better for collaborations with elected officials. Validation and reliability work would be required to optimize issues of reliability, validity, and generalizability. Such a study would also want to consider whether there are instances in which the indicators may obstruct the partnership.” Another area for future study would be the maturation of such partnerships, with considerations for the time frames needed to show a shift in early versus mature partnerships.2

We want to hear from you!

Assessing community engagement involves the participation of many stakeholders. Click here to share feedback on these resources, or email [email protected] and include “measure engagement” in the subject line to learn more about the NAM’s Assessing Community Engagement project.

Related Products