Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement

Community Ownership and Preparedness Index

KEY FEATURES

COMMUNITY/ GEOGRAPHY

Female sex workers

High-risk men who have sex with men

Transgender individuals

Injection drug users

HIV prevention

India

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT OUTCOMES

Strengthened partnerships + alliances

Broad alignment

Diversity + inclusivity

Partnerships + opportunities

Acknowledgment, visibility, recognition

Trust

Shared power

Structural supports for community engagement

Improved health + health care programs + policies

Broad alignment

Actionable, implemented, recognized solutions

Thriving communities

Community capacity + connectivity

Community power

Community resiliency

PLACE(S) OF INSTRUMENT USE

Community/community-based organization

Non-governmental organizations

LANGUAGE TRANSLATIONS

Not specified

PSYCHOMETRIC PROPERTIES

Content validity

Predictive validity

YEAR OF USE

2009-2013

Assessment Instrument Overview

The Community Ownership and Preparedness Index (COPI) has 23 questions and is used by communities. It assesses progress in community organizational development and monitors the transition readiness of community-based groups.

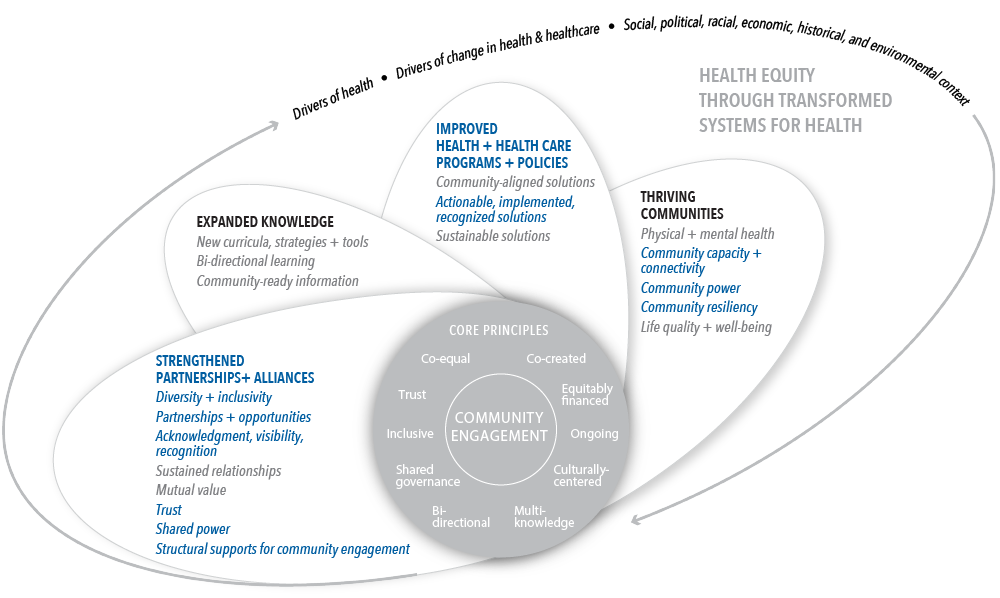

Alignment with Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement Conceptual Model

The questions in COPI were aligned to the Assessing Community Engagement Conceptual Model. Figure 1 displays the alignment of COPI with the Conceptual Model domain(s) and indicator(s). Where an instrument is mapped broadly with a domain or with a specific indicator, the figure shows the alignment in blue font.

Table 1 displays the alignment of the questions of the COPI with the Conceptual Model domain(s) and indicator(s). The table shows, from left to right, the aligned Conceptual Model domain(s) and indicator(s) and the individual questions from the COPI transcribed as they appear in the instrument (with minor formatting changes for clarity).

| CONCEPTUAL MODEL DOMAIN(S) AND INDICATOR(S) | ASSESSMENT INSTRUMENT QUESTIONS |

| STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Broad alignment with all indicators in this domain | 11.) Committees formed for crisis response and advocacy; committees are meeting regularly. |

| STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Diversity + inclusivity | 8.) Inclusion of all groups in leadership team.

14.) Regular increase in outreach. |

| STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Partnerships + opportunities | 15.) Networking with networks.

16.) Networking with other bodies. |

| STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Acknowledgment, visibility, recognition | 1.) Leadership team has demonstrated capacity to show solidarity during crises faced by community members. |

| STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Trust | 7.) System in place for leadership’s accountability to community members. i. Leadership’s accountability towards community members. ii. Committees’ accountability to community members.* |

| STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Shared power | 3.) Leadership team (LT) is capable of setting its own agenda and of emerging from the shadow of the implementing partner. i. LT exists as an entity and meets regularly. ii. LT independently sets agenda for its meetings. iii. LT engages with the implementing partner over disagreements on a strong footing.

9.) Defined system for decision-making, with community-based group becoming the decision-maker.* 10.) System to promote community involvement in strategic decision-making.* |

| STRENGTHENED PARTNERSHIPS + ALLIANCES; Structural supports for community engagement | 6.) Participatory selection process for the leadership. i. Participatory selection process for leadership team and office bearers. ii. Participatory selection process for committee members.

7.) System in place for leadership’s accountability to community members. i. Leadership’s accountability towards community members. ii. Committees’ accountability to community members.* 9.) Defined system for decision-making, with community-based group becoming the decision-maker.* 10.) System to promote community involvement in strategic decision-making.* |

| IMPROVED HEALTH + HEALTH CARE PROGRAMS + POLICIES; Broad alignment with all indicators in this domain | 18.) Leadership is competent and confident in contributing towards project processes. i. Awareness and implementation. ii. Monitoring and strategizing. |

| IMPROVED HEALTH + HEALTH CARE PROGRAMS + POLICIES; Actionable, implemented, recognized solutions | 17.) Leadership is aware of the requirements for managing organizations and can demonstrate its ability to do so. i. Awareness of compliance with statutory requirements as well as systems to minimize legal and financial risks and risks due to adverse publicity. ii. Demonstrated capacity to manage strong financial, accounting and administrative systems. |

| Thriving communities; Community capacity + connectivity | 5.) Leadership team has made efforts to develop second-line leadership.

12.) Strong, diversified resource base. i. Financial. ii. Non-financial. 13.) Entry into formal economy. Leadership team has demonstrated capacity to

|

| Thriving communities; Community power | Leadership team has demonstrated

|

| Thriving communities; Community resiliency | Leadership team has

|

*Note that these questions are duplicated to reflect their alignment with multiple domains and/or indicators in the Conceptual Model.

Table 1 | Community Ownership and Preparedness Index questions and alignment with the domain(s) and indicator(s) of the Assessing Community Engagement Conceptual Model

ASSESSMENT INSTRUMENT BACKGROUND

Context of instrument development/use

This article discusses COPI, which was developed to inform communities about progress in community organizational development and monitor the transition readiness of community-based groups. COPI assessed Avahan, the India AIDS Initiative, which is a 10-year, large-scale HIV prevention intervention. The Avahan community includes high-risk individuals such as “female sex workers, high-risk men who have sex with men, transgender [individuals], and injecting drug users” who engage with the program through informal and formal meetings and engagement activities.

The objectives of COPI were to assess the implementation and effectiveness of community mobilization to ensure the transition of program management and funding to the government; assist partners in the process of community mobilization; advance large-scale implementation through replicating lessons learned from community mobilization; and make inferences regarding community mobilization using data collected through information systems and other surveys, as well as improved HIV prevention outcomes.

Instrument description/purpose

COPI focuses on four essential dimensions needed to understand the transition readiness of community-based groups: “(1) leadership, governance and decision-making; (2) sustainability through resource mobilisation and networking; (3) project management; and (4) engagement with the state and wider society.”

The instrument assesses the dimensions above using eight broad parameters:

- Engagement with the state

- Engagement with other key influencers

- Project and risk management

- Resource mobilization

- Decision-making system

- Governance

- Leadership

- Community collective network

COPI has 23 questions that capture the essential eight dimensions and parameters above, as well as express practical and operational participatory concepts. The article states that “COPI assigns weights to different indicators and parameters reflecting their relative importance to transition readiness.” Additional details on the response options were not presented in the article.

COPI can be accessed here: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech-2011-200590.

Engagement involved in developing, implementing, or evaluating the assessment instrument

COPI was developed using a participatory and iterative process. The process included the following stages: “a review of background material and theory as well as learning from the experiences of Indian [community-based groups] working in HIV prevention; design of the study framework and related indicators and parameters; weighting of indicators; and development and pilot testing of the survey tools.” Facilitated discussions and focus groups were held with high-risk communities, and insights were supplemented with input from statisticians, sociologists, anthropologists, demographers, and gender experts. Additionally, a process for sharing data, including data collection and analysis across six Indian states with the community-based groups was built into the survey design. This allowed community-based groups to use the data to make decisions about their organizations and activities, empowering and serving these groups directly.

Additional information on populations engaged in instrument use

Not specified.

Notes

- Potential limitations: Further evaluation is needed to understand the predictive validity of COPI.

- Important findings: The COPI “methodology is intended to make the process of monitoring part of the community mobilisation programme itself.” The instrument was also intended to empower the leaders of community-based groups. For example, through the use of intensive interviews with the members and leaders of community-based groups, the instrument content informed leaders of the “programme quality, rights and entitlements, and approaches to addressing stigma, and the survey process itself,” ultimately making discussion of critical issues possible. Additionally, during facilitated discussions on the COPI scores, community-based groups often reflected on the operational implications. Notably, “these discussions were designed to challenge power dynamics, expand the vision of [community-based groups] to opportunities beyond the programme, and build collective agency. The experience of implementing the survey validated the design’s effectiveness as a participatory action tool and demonstrated that monitoring can in effect be a useful intervention in itself.” Additionally, COPI “could be measured and aggregated at the level of individual [community-based groups] as well as state and national levels.”

- Supplemental information: Additional research has been conducted using COPI with other populations and HIV/AIDS programs. The findings from the research can be found in the following articles:

- Narayanan, P., K. Moulasha, T. Wheeler, J. Baer, S. Bharadwaj, T. V. Ramanathan, and T. Thomas. 2012. Monitoring community mobilisation and organisational capacity among high-risk groups in a large-scale HIV prevention programme in India: selected findings using a Community Ownership and Preparedness Index. Journal of Epidemiolgical Community Health 66:ii34-eii41. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2012-201065.

- Chakravarthy, J. B., S. V. Joseph, P. Pelto, and D. Kovvali. 2012. Community mobilisation programme for female sex workers in coastal Andhra Pradesh, India: processes and their effects. Journal of Epidemiological Community Health 66:ii78-86. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2011-200487.

- Sadhu, S., A. R. Manukonda, A. R. Yeruva, S. K. Patel, and N. Saggurti. 2014. Role of a community-to-community learning strategy in the institutionalization of community mobilization among female sex workers in India. PLoS One 9(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090592.

We want to hear from you!

Assessing community engagement involves the participation of many stakeholders. Click here to share feedback on these resources, or email [email protected] and include “measure engagement” in the subject line to learn more about the NAM’s Assessing Community Engagement project.

Related Products