Many communities across the United States are working to reduce health disparities and finding ways to engage residents and organizations in difficult conversations about what it takes to improve health and well-being for all. These conversations are rooted in an understanding that health is a right, not a privilege, and that health inequities are not just a matter of individual choice but are profoundly shaped by interconnected social and structural drivers that impact people’s lives. To make meaningful progress, communities engaged in this work must discuss and address both the social conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, as well as the broader structural factors that shape the distribution of power, money, and resources and systematically limit opportunities for all people to achieve the best possible health (Heller, 2024; CMS, 2025). Multi-sector, community-driven partnerships that work to address the unmet health and social needs of the residents and communities they serve can be effective vehicles for both conversation and action (Mittmann et al., 2022).

In October 2024, The George Washington University’s Funders Forum on Accountable Health and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s (NASEM) Roundtable on Population Health Improvement co-hosted a webinar on multi-sector, community-driven partnerships as an intentional strategy to advance health equity, which is the state in which “everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible” (NASEM, 2024; Braveman, 2017).

This commentary summarizes the key takeaways from the webinar, highlighting the work of two multi-sector organizations in California and Washington that have developed strong partnerships and trusting relationships to begin to discuss and address social and structural drivers of health in their communities, with the ultimate goal of advancing health equity. It also presents a messaging strategy developed by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) to help similar initiatives communicate about structural barriers to health equity, with an emphasis on structural racism (RWJF, 2023b). Unlike interpersonal racism, which refers to individual acts of prejudice and bias, structural racism is when laws, policies, institutional practices, and norms—regardless of intent—drive racial disparities across systems such as health care, housing, education, employment, criminal justice, and so on (Furtado, 2023).

Since the webinar took place, the broader context in which these partnerships operate has continued to evolve. These changes include cuts to federal funding, reductions in force, and the reconciliation act (HR 1, enacted as Public Law 119-21), which the Congressional Budget Office estimates could increase the number of uninsured individuals by around 10 million in 2034; furthermore, the scheduled expiration of enhanced Affordable Care Act premium tax credits could add up to another four million, bringing the total projected coverage loss to more than 14 million people by that year (CBO, 2025). Also included are executive actions to reduce support for diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts. The shifting landscape reinforces the importance of sustained, community-driven efforts like those described in the following sections to advance health and well-being for all.

Multi-Sector, Community-Driven Partnerships

Accountable communities for health (ACHs) and other similar multi-sector, community-driven partnerships work to address the unmet health and social needs of the residents and communities they serve (Mittmann et al., 2022). These initiatives engage various sectors including health care, public health, social services, and other local partners to implement a portfolio of interventions that can improve individual and community health outcomes. They also build trust among community members, by centering community voice in decision making and resource allocation. Highlighted in the following sections are two examples of initiatives working to make meaningful change through authentic community partnership.

Safety and Healing in Networks of Equity (SHINE) in California

Safety and Healing in Networks of Equity (SHINE) is a California project “stewarded by Prevention Institute, co-created with a Learning Community of five community collaboratives, and supported by the Blue Shield of California Foundation” (Prevention Institute, n.d.b). The five SHINE community collaboratives, located across California, bring together health care, social services, and community organizations to promote safety and healing and address the root causes of domestic violence and other health inequities (Prevention Institute, n.d.b). They do this by fostering community leadership and power, and advocating for policies, systems, and resources that support the safety and healing of populations harmed by domestic violence (Prevention Institute, n.d.b).

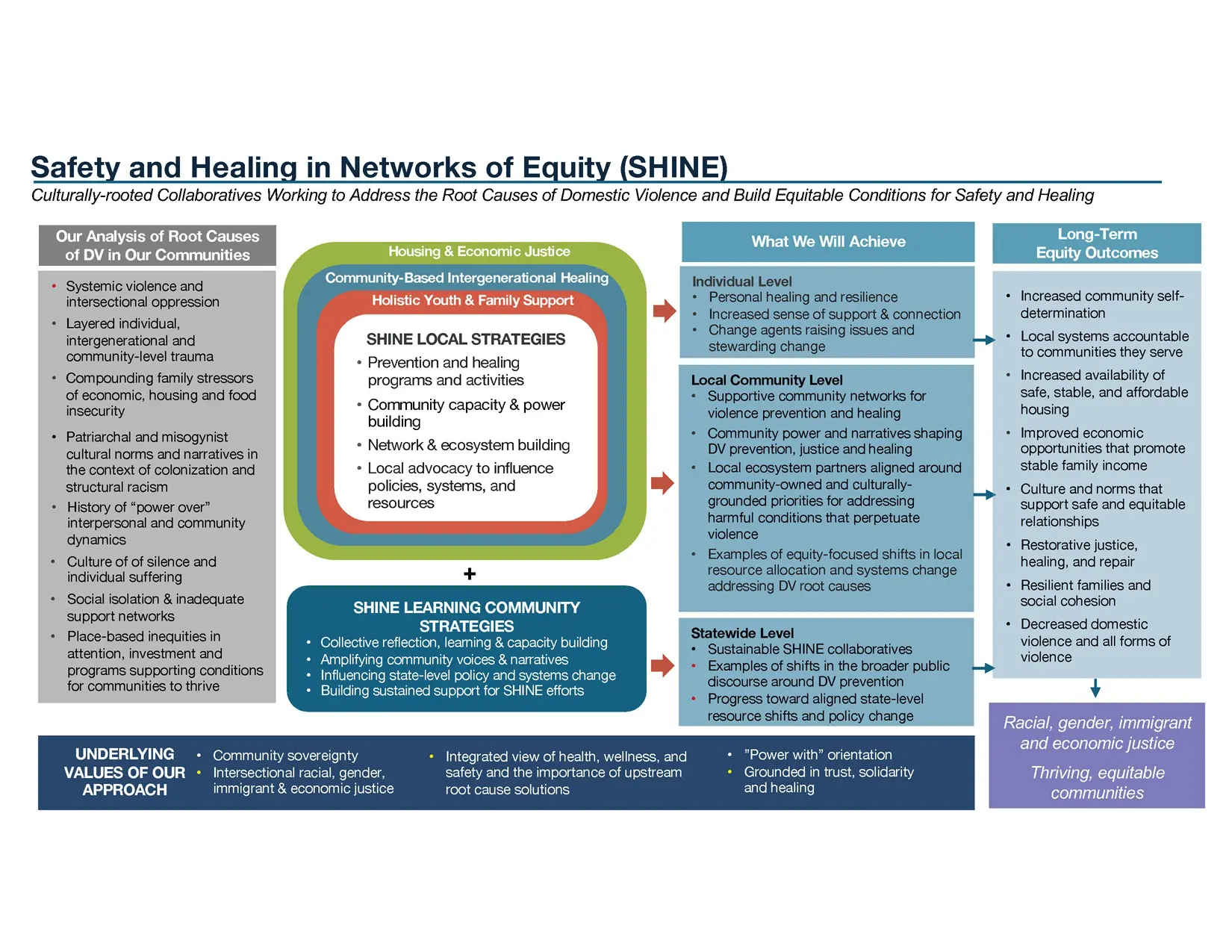

In 2024, Prevention Institute and SHINE collaborative representatives developed an internal project framework that identifies: (1) the conditions that contribute to domestic violence in communities, (2) strategies to address these conditions at the local level, (3) strategies to support and amplify this local work, and (4) the project’s anticipated outcomes at the individual, community, and statewide levels for long-term change (see Figure 1). Importantly, the framework identifies the underlying values that guide the work of SHINE community collaboratives, which center community power and leadership; acknowledge that individuals’ and populations’ experiences of health and well-being can be shaped by their race, gender, and class; and address social and structural drivers of health.

Figure 1| Safety and Healing in Networks of Equity (SHINE) Project Framework SOURCE: Prevention Institute. 2024. SHINE Project Framework. Available at: https://preventioninstitute.org/publications/shine-project-framework (accessed January 17, 2025).

The Center at McKinleyville in Rural Humboldt County, California

One of SHINE’s five community collaboratives is The Center at McKinleyville (The Center), led by the McKinleyville Family Resource Center in Humboldt County, California—a rural area home to many Indigenous peoples from the Wiyot, Yurok, Karuk, Hupa, Tolowa, and Wailaki tribes. The Center promotes collaboration across agencies and organizations in order to build the community capacity necessary to address social and structural drivers of domestic violence. Specifically, The Center’s focus is on community engagement and power building, as well as examining the way power manifests and can be addressed at every level of their work including internal, interpersonal, institutional, and structural levels (NASEM, 2024). Internally, The Center invests in staff members’ well-being and leadership development to better equip them to serve their community. Interpersonally, The Center works to build trust with its partners and encourage collective projects that have tangible outcomes for community members. Institutionally, The Center Partnership Committee and Community Advisory Group work to develop and adopt internal policies and values that guide their work. Structurally, examples of The Center’s recent work include partnering with California Department of Social Services on a guaranteed income pilot project for pregnant and parenting people, and implementing a grant project to ensure that Indigenous art is incorporated into a local park. Through this work at every level, The Center has learned the importance of being transparent about its values, having a clear purpose and constant evaluation, and working with innovative partners.

Better Health Together in Spokane, Washington

Better Health Together is an ACH in Spokane, Washington, that serves six counties in the eastern part of the state and the Reservations of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, the Spokane Tribe of Indians, and the Kalispel Tribe of Indians (BHT, n.d.a). Established 10 years ago, it is one of nine ACHs in a statewide regional network that now operates community care hubs to better integrate health and social care (BHT, 2024). The organization’s vision is “an integrated and antiracist health system accountable for better health for ALL in eastern Washington” to “radically improve the health of the region” (BHT, n.d.b). This work is made possible through Better Health Together’s ongoing investment in data, capacity building, and administrative support. These investments provide the foundation for long-term impact through, for example, development of strategic measures that capture multiple dimensions of community health; enhancement of data and IT infrastructure; and creation of dependable and sustainable funds by braiding funds from diverse funding streams including federal and state grants, philanthropic and other private funding, and contracts with Medicaid managed care.

Notably, Better Health Together has worked collaboratively with the statewide regional network of ACHs and Washington’s Department of Health and Health Care Authority to develop and align around a statewide measurement strategy to help them determine if the community care hub model is working to improve care delivery systems (NASEM, 2024). These performance measures are organized around three questions: what and how much did they do? how well did they do it? and is anyone or anything better off? As part of this effort, Better Health Together is documenting its progress in several areas, including how they are (1) expanding the ability of community-based organizations to connect people to health and social services, (2) fostering community leadership and power, (3) improving linkages between clinical and social care services and resources, and (4) enhancing the economic and social well-being of the community-based workforce (BHT, 2024).

Over the years, Better Health Together has deepened its commitment to grounding its work in community voice by ensuring the composition of its board and committees is more reflective of the communities experiencing the greatest health disparities, contracting with community-based organizations that employ a trusted messenger workforce, and investing in that community-based workforce through training and networking opportunities (NASEM, 2024). Through meaningful partnership, Better Health Together works to continuously build trust with the communities it serves.

Having the Conversation

The work of the SHINE community collaboratives in California and Better Health Together in Washington highlights the importance of centering and engaging communities to advance health equity. These efforts also demonstrate that multi-sector, community-driven organizations are well-positioned to build trust, foster shared leadership, and elevate community power and voice. They do this by listening to and acting on community members’ interests and needs, and being willing to engage in honest, often difficult conversations with diverse audiences about social and structural drivers of health and health equity. RWJF and its research partners have developed a messaging strategy to facilitate these conversations, with a focus on communicating the connection between structural racism and health that has proved effective in reaching and engaging people who are open to conversations about this topic (RWJF, 2023b). This tested approach helps people think beyond the individual level to a structural or systems approach, and includes an intentional and informed sequence of message components (RWJF, 2023b):

- A shared, values-based ideal statement

- A positive vision and problem statement rooted in place and the people who live there

- A clear call to action and unity statement

Using this messaging approach makes it easier for people to understand the impact of structural racism on health and view themselves as part of the solution. It also highlights how, through collective action, barriers can be broken down so that everyone can achieve their best health and well-being, no matter one’s race, class, gender, or other factors that shape identity.

An example of this messaging approach is explained in an RWJF video titled “Building a bridge to health for all people” (RWJF, 2023a). Importantly, when communicating about these complex issues, RWJF and its research partners emphasize avoiding jargon and instead using plain language that is easy for everyone to understand. This approach facilitates conversations that bring participants closer together rather than creating distance or inaccessibility. The importance of using plain language is discussed further in an RWJF video titled “Make it plain” (RWJF, 2024).

Key Takeaways

Multi-sector, community-driven work that aims to create more just systems can and must flourish in a variety of contexts, including within a range of political and policy climates, and even within areas that have seemingly unfavorable conditions for doing health equity and racial justice work. Although engaging residents and organizations in conversations about what it takes to improve health and well-being for all can be difficult, as illustrated in the examples previously discussed, it is both possible and necessary. Notably, the importance of intentionality and persistence in having these conversations and taking action cannot be overstated. The Prevention Institute’s practice of “continuous equity improvement” was repeatedly referenced in the webinar discussion to describe the work of these partnerships in their communities (Prevention Institute, n.d.a). Beyond how the work is described and who champions it within the organization or community, it is important to be strategic and to think critically about how to best position multi-sector, community-driven efforts for success:

- Communities need to be empowered and community-based organizations need to be appropriately resourced to facilitate this work from the bottom up. Community members need a voice and decision making power at governance tables for priority setting and resource allocation to have maximum benefit. Centering community in governance structures also helps with trust building and shoring up people power. This type of collaboration is hard work, and it requires active listening, learning, and humility.

- Progress needs to be measured, documented, and shared. Snapshotting or quantifying the results of this work, however, is not easily done and requires a longer and more complex view of the impacts of multi-sector, community-driven efforts. The value of ACHs and other similar multi-sector, community-driven partnerships can be demonstrated along a continuum (Reid et al., 2024). In the short term, there is return on investment—cost reduction and quality improvement measures typically used in health care settings. In the medium term, there is community capacity building—resources to support the organizational infrastructure and community resources to address health-related social needs identified through screening, referral, and navigation mechanisms. In the long term, there is the civic infrastructure or assets that move beyond individual-level impact. This is about these partnerships being well-positioned to address broader policy and systems change that contribute to poor health outcomes.

- In order to be sustainable, gain momentum, and show progress, community-based work to address health equity has to be opportunistic. Multi-sector partnerships should be flexible and focus on issues where there are clear community needs, identifiable opportunities for quick wins, clear bipartisan interest in a set of issues, or strong alignment with federal, state, or local public and private sector interest.

Last, as noted by the communities previously discussed and by others engaged in community-driven work to address social and structural drivers of health and advance health equity, there are missteps and past injustices to contend with when trying to shift power and elevate community voice for change. Discomfort is inherent to this work. Embracing the assets and strengths of the community is key to making progress toward systemic change and should not be overlooked or underestimated.

Join the Conversation!

New from #NAMPerspectives: Multi-Sector, Community-Driven Partnerships: An Intentional Strategy to Advance Health Equity. Read now: https://doi.org/10.31478/202510a

According to authors of a new #NAMPerpsectives commentary, embracing the assets and strengths of the community is key to making progress toward systemic change. Read more: https://doi.org/10.31478/202510a

References

BHT (Better Health Together). 2024. Introducing the Community Care Hub and our Social Care Network 1.0. Available at: https://betterhealthtogether.org/introducing-the-community-care-hub-and-our-social-care-network-10/ (accessed January 17, 2025).

BHT. n.d.a. Better health starts together. Available at: https://www.betterhealthtogether.org/ (accessed January 7, 2025).

BHT. n.d.b. Mission & vision. Available at: https://www.betterhealthtogether.org/about-bht (accessed January 7, 2025).

Braveman, P., E. Arkin, T. Orleans, D. Proctor, and A. Plough. 2017. What is health equity? And What Difference Does a Definition Make? Princeton, NJ: The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Available at: https://www.rwjf.org/en/insights/our-research/2017/05/what-is-health-equity-.html (accessed September 4, 2025).

CBO (Congressional Budget Office). 2025. Estimated budgetary effects of Public Law 119-21, to provide for reconciliation pursuant to Title II of H. Con. Res. 14, relative to CBO’s January 2025 baseline. Available at: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61570 (accessed August 25, 2025).

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2025. Social drivers of health and health-related social needs. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/key-concepts/social-drivers-health-and-health-related-social-needs (accessed September 16, 2025).

Furtado, K., A. Verdeflor, and T. Waidmann. 2023. A conceptual map of structural racism in health care. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. Available at: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/conceptual-map-structural-racism-health-care (accessed January 7, 2025).

Heller, J. C., M. L. Givens, S. P. Johnson, and D. A. Kindig. 2024. Keeping it political and powerful: Defining the structural determinants of health. The Milbank Quarterly 102(2):351-366. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12695.

Mittmann, H., J. Heinrich, and J. Levi. 2022. Accountable communities for health: What we are learning from recent evaluations. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/202210a.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2024. Multi-Sector, community-based partnerships as an intentional strategy to advance health equity: A webinar. Available at: https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/43916_10-2024_multi-sector-community-based-partnerships-as-an-intentional-strategy-to-advance-health-equity-a-webinar (accessed January 7, 2025).

Prevention Institute. 2024. SHINE Project Framework. Available at: https://preventioninstitute.org/publications/shine-project-framework (accessed January 17, 2025).

Prevention Institute. n.d.a. Applying research and data for continuous equity improvement. Available at: https://preventioninstitute.org/health-equity-practice-module-3-advancing-policy-systems-change-resources-section-2-implementation-0 (accessed April 10, 2025).

Prevention Institute. n.d.b. Safety and Healing in Networks of Equity (SHINE). Available at: https://www.preventioninstitute.org/projects/safety-and-healing-networks-equity-shine (accessed January 7, 2025).

Reid, A. M., J. Heinrich, J. Trott, and H. Mittmann. 2024. States demonstrating the business case for multisector efforts: An emerging value framework. NAM Perspectives. Commentary, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/202408a.

RWJF (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation). 2024. “Make it plain.” YouTube video, 2 min., 2 sec. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lEJX5gKrMCc (accessed January 7, 2025).

RWJF. 2023a. “Building a bridge to health for all people.” YouTube video, 2 min., 25 sec. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iIBmJjWXp4Q (accessed January 7, 2025).

RWJF. 2023b. Structural racism and health: Messages to inspire broader understanding and action. Available at: https://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/toolkits/toolkits/2023/rwjf475829 (accessed September 4, 2025).

Multi-Sector, Community-Driven Partnerships: An Intentional Strategy to Advance Health Equity

Anne Morris Reid

Jennifer Trott

Many communities across the United States are working to reduce health disparities and finding ways to engage residents and organizations in difficult conversations about what it takes to improve health and well-being for all. These conversations are rooted in an understanding that health is a right, not a privilege, and that health inequities are not just a matter of individual choice but are profoundly shaped by interconnected social and structural drivers that impact people’s lives. To make meaningful progress, communities engaged in this work must discuss and address both the social conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, as well as the broader structural factors that shape the distribution of power, money, and resources and systematically limit opportunities for all people to achieve the best possible health (Heller, 2024; CMS, 2025). Multi-sector, community-driven partnerships that work to address the unmet health and social needs of the residents and communities they serve can be effective vehicles for both conversation and action (Mittmann et al., 2022).

In October 2024, The George Washington University’s Funders Forum on Accountable Health and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s (NASEM) Roundtable on Population Health Improvement co-hosted a webinar on multi-sector, community-driven partnerships as an intentional strategy to advance health equity, which is the state in which “everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible” (NASEM, 2024; Braveman, 2017).

This commentary summarizes the key takeaways from the webinar, highlighting the work of two multi-sector organizations in California and Washington that have developed strong partnerships and trusting relationships to begin to discuss and address social and structural drivers of health in their communities, with the ultimate goal of advancing health equity. It also presents a messaging strategy developed by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) to help similar initiatives communicate about structural barriers to health equity, with an emphasis on structural racism (RWJF, 2023b). Unlike interpersonal racism, which refers to individual acts of prejudice and bias, structural racism is when laws, policies, institutional practices, and norms—regardless of intent—drive racial disparities across systems such as health care, housing, education, employment, criminal justice, and so on (Furtado, 2023).

Since the webinar took place, the broader context in which these partnerships operate has continued to evolve. These changes include cuts to federal funding, reductions in force, and the reconciliation act (HR 1, enacted as Public Law 119-21), which the Congressional Budget Office estimates could increase the number of uninsured individuals by around 10 million in 2034; furthermore, the scheduled expiration of enhanced Affordable Care Act premium tax credits could add up to another four million, bringing the total projected coverage loss to more than 14 million people by that year (CBO, 2025). Also included are executive actions to reduce support for diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts. The shifting landscape reinforces the importance of sustained, community-driven efforts like those described in the following sections to advance health and well-being for all.

Multi-Sector, Community-Driven Partnerships

Accountable communities for health (ACHs) and other similar multi-sector, community-driven partnerships work to address the unmet health and social needs of the residents and communities they serve (Mittmann et al., 2022). These initiatives engage various sectors including health care, public health, social services, and other local partners to implement a portfolio of interventions that can improve individual and community health outcomes. They also build trust among community members, by centering community voice in decision making and resource allocation. Highlighted in the following sections are two examples of initiatives working to make meaningful change through authentic community partnership.

Safety and Healing in Networks of Equity (SHINE) in California

Safety and Healing in Networks of Equity (SHINE) is a California project “stewarded by Prevention Institute, co-created with a Learning Community of five community collaboratives, and supported by the Blue Shield of California Foundation” (Prevention Institute, n.d.b). The five SHINE community collaboratives, located across California, bring together health care, social services, and community organizations to promote safety and healing and address the root causes of domestic violence and other health inequities (Prevention Institute, n.d.b). They do this by fostering community leadership and power, and advocating for policies, systems, and resources that support the safety and healing of populations harmed by domestic violence (Prevention Institute, n.d.b).

In 2024, Prevention Institute and SHINE collaborative representatives developed an internal project framework that identifies: (1) the conditions that contribute to domestic violence in communities, (2) strategies to address these conditions at the local level, (3) strategies to support and amplify this local work, and (4) the project’s anticipated outcomes at the individual, community, and statewide levels for long-term change (see Figure 1). Importantly, the framework identifies the underlying values that guide the work of SHINE community collaboratives, which center community power and leadership; acknowledge that individuals’ and populations’ experiences of health and well-being can be shaped by their race, gender, and class; and address social and structural drivers of health.

Figure 1| Safety and Healing in Networks of Equity (SHINE) Project Framework SOURCE: Prevention Institute. 2024. SHINE Project Framework. Available at: https://preventioninstitute.org/publications/shine-project-framework (accessed January 17, 2025).

The Center at McKinleyville in Rural Humboldt County, California

One of SHINE’s five community collaboratives is The Center at McKinleyville (The Center), led by the McKinleyville Family Resource Center in Humboldt County, California—a rural area home to many Indigenous peoples from the Wiyot, Yurok, Karuk, Hupa, Tolowa, and Wailaki tribes. The Center promotes collaboration across agencies and organizations in order to build the community capacity necessary to address social and structural drivers of domestic violence. Specifically, The Center’s focus is on community engagement and power building, as well as examining the way power manifests and can be addressed at every level of their work including internal, interpersonal, institutional, and structural levels (NASEM, 2024). Internally, The Center invests in staff members’ well-being and leadership development to better equip them to serve their community. Interpersonally, The Center works to build trust with its partners and encourage collective projects that have tangible outcomes for community members. Institutionally, The Center Partnership Committee and Community Advisory Group work to develop and adopt internal policies and values that guide their work. Structurally, examples of The Center’s recent work include partnering with California Department of Social Services on a guaranteed income pilot project for pregnant and parenting people, and implementing a grant project to ensure that Indigenous art is incorporated into a local park. Through this work at every level, The Center has learned the importance of being transparent about its values, having a clear purpose and constant evaluation, and working with innovative partners.

Better Health Together in Spokane, Washington

Better Health Together is an ACH in Spokane, Washington, that serves six counties in the eastern part of the state and the Reservations of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, the Spokane Tribe of Indians, and the Kalispel Tribe of Indians (BHT, n.d.a). Established 10 years ago, it is one of nine ACHs in a statewide regional network that now operates community care hubs to better integrate health and social care (BHT, 2024). The organization’s vision is “an integrated and antiracist health system accountable for better health for ALL in eastern Washington” to “radically improve the health of the region” (BHT, n.d.b). This work is made possible through Better Health Together’s ongoing investment in data, capacity building, and administrative support. These investments provide the foundation for long-term impact through, for example, development of strategic measures that capture multiple dimensions of community health; enhancement of data and IT infrastructure; and creation of dependable and sustainable funds by braiding funds from diverse funding streams including federal and state grants, philanthropic and other private funding, and contracts with Medicaid managed care.

Notably, Better Health Together has worked collaboratively with the statewide regional network of ACHs and Washington’s Department of Health and Health Care Authority to develop and align around a statewide measurement strategy to help them determine if the community care hub model is working to improve care delivery systems (NASEM, 2024). These performance measures are organized around three questions: what and how much did they do? how well did they do it? and is anyone or anything better off? As part of this effort, Better Health Together is documenting its progress in several areas, including how they are (1) expanding the ability of community-based organizations to connect people to health and social services, (2) fostering community leadership and power, (3) improving linkages between clinical and social care services and resources, and (4) enhancing the economic and social well-being of the community-based workforce (BHT, 2024).

Over the years, Better Health Together has deepened its commitment to grounding its work in community voice by ensuring the composition of its board and committees is more reflective of the communities experiencing the greatest health disparities, contracting with community-based organizations that employ a trusted messenger workforce, and investing in that community-based workforce through training and networking opportunities (NASEM, 2024). Through meaningful partnership, Better Health Together works to continuously build trust with the communities it serves.

Having the Conversation

The work of the SHINE community collaboratives in California and Better Health Together in Washington highlights the importance of centering and engaging communities to advance health equity. These efforts also demonstrate that multi-sector, community-driven organizations are well-positioned to build trust, foster shared leadership, and elevate community power and voice. They do this by listening to and acting on community members’ interests and needs, and being willing to engage in honest, often difficult conversations with diverse audiences about social and structural drivers of health and health equity. RWJF and its research partners have developed a messaging strategy to facilitate these conversations, with a focus on communicating the connection between structural racism and health that has proved effective in reaching and engaging people who are open to conversations about this topic (RWJF, 2023b). This tested approach helps people think beyond the individual level to a structural or systems approach, and includes an intentional and informed sequence of message components (RWJF, 2023b):

Using this messaging approach makes it easier for people to understand the impact of structural racism on health and view themselves as part of the solution. It also highlights how, through collective action, barriers can be broken down so that everyone can achieve their best health and well-being, no matter one’s race, class, gender, or other factors that shape identity.

An example of this messaging approach is explained in an RWJF video titled “Building a bridge to health for all people” (RWJF, 2023a). Importantly, when communicating about these complex issues, RWJF and its research partners emphasize avoiding jargon and instead using plain language that is easy for everyone to understand. This approach facilitates conversations that bring participants closer together rather than creating distance or inaccessibility. The importance of using plain language is discussed further in an RWJF video titled “Make it plain” (RWJF, 2024).

Key Takeaways

Multi-sector, community-driven work that aims to create more just systems can and must flourish in a variety of contexts, including within a range of political and policy climates, and even within areas that have seemingly unfavorable conditions for doing health equity and racial justice work. Although engaging residents and organizations in conversations about what it takes to improve health and well-being for all can be difficult, as illustrated in the examples previously discussed, it is both possible and necessary. Notably, the importance of intentionality and persistence in having these conversations and taking action cannot be overstated. The Prevention Institute’s practice of “continuous equity improvement” was repeatedly referenced in the webinar discussion to describe the work of these partnerships in their communities (Prevention Institute, n.d.a). Beyond how the work is described and who champions it within the organization or community, it is important to be strategic and to think critically about how to best position multi-sector, community-driven efforts for success:

Last, as noted by the communities previously discussed and by others engaged in community-driven work to address social and structural drivers of health and advance health equity, there are missteps and past injustices to contend with when trying to shift power and elevate community voice for change. Discomfort is inherent to this work. Embracing the assets and strengths of the community is key to making progress toward systemic change and should not be overlooked or underestimated.

Join the Conversation!

New from #NAMPerspectives: Multi-Sector, Community-Driven Partnerships: An Intentional Strategy to Advance Health Equity. Read now: https://doi.org/10.31478/202510a

According to authors of a new #NAMPerpsectives commentary, embracing the assets and strengths of the community is key to making progress toward systemic change. Read more: https://doi.org/10.31478/202510a

References

BHT (Better Health Together). 2024. Introducing the Community Care Hub and our Social Care Network 1.0. Available at: https://betterhealthtogether.org/introducing-the-community-care-hub-and-our-social-care-network-10/ (accessed January 17, 2025).

BHT. n.d.a. Better health starts together. Available at: https://www.betterhealthtogether.org/ (accessed January 7, 2025).

BHT. n.d.b. Mission & vision. Available at: https://www.betterhealthtogether.org/about-bht (accessed January 7, 2025).

Braveman, P., E. Arkin, T. Orleans, D. Proctor, and A. Plough. 2017. What is health equity? And What Difference Does a Definition Make? Princeton, NJ: The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Available at: https://www.rwjf.org/en/insights/our-research/2017/05/what-is-health-equity-.html (accessed September 4, 2025).

CBO (Congressional Budget Office). 2025. Estimated budgetary effects of Public Law 119-21, to provide for reconciliation pursuant to Title II of H. Con. Res. 14, relative to CBO’s January 2025 baseline. Available at: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61570 (accessed August 25, 2025).

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2025. Social drivers of health and health-related social needs. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/key-concepts/social-drivers-health-and-health-related-social-needs (accessed September 16, 2025).

Furtado, K., A. Verdeflor, and T. Waidmann. 2023. A conceptual map of structural racism in health care. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. Available at: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/conceptual-map-structural-racism-health-care (accessed January 7, 2025).

Heller, J. C., M. L. Givens, S. P. Johnson, and D. A. Kindig. 2024. Keeping it political and powerful: Defining the structural determinants of health. The Milbank Quarterly 102(2):351-366. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12695.

Mittmann, H., J. Heinrich, and J. Levi. 2022. Accountable communities for health: What we are learning from recent evaluations. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/202210a.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2024. Multi-Sector, community-based partnerships as an intentional strategy to advance health equity: A webinar. Available at: https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/43916_10-2024_multi-sector-community-based-partnerships-as-an-intentional-strategy-to-advance-health-equity-a-webinar (accessed January 7, 2025).

Prevention Institute. 2024. SHINE Project Framework. Available at: https://preventioninstitute.org/publications/shine-project-framework (accessed January 17, 2025).

Prevention Institute. n.d.a. Applying research and data for continuous equity improvement. Available at: https://preventioninstitute.org/health-equity-practice-module-3-advancing-policy-systems-change-resources-section-2-implementation-0 (accessed April 10, 2025).

Prevention Institute. n.d.b. Safety and Healing in Networks of Equity (SHINE). Available at: https://www.preventioninstitute.org/projects/safety-and-healing-networks-equity-shine (accessed January 7, 2025).

Reid, A. M., J. Heinrich, J. Trott, and H. Mittmann. 2024. States demonstrating the business case for multisector efforts: An emerging value framework. NAM Perspectives. Commentary, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/202408a.

RWJF (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation). 2024. “Make it plain.” YouTube video, 2 min., 2 sec. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lEJX5gKrMCc (accessed January 7, 2025).

RWJF. 2023a. “Building a bridge to health for all people.” YouTube video, 2 min., 25 sec. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iIBmJjWXp4Q (accessed January 7, 2025).

RWJF. 2023b. Structural racism and health: Messages to inspire broader understanding and action. Available at: https://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/toolkits/toolkits/2023/rwjf475829 (accessed September 4, 2025).

Mittmann, H., A. M. Reid, and J. Trott. 2025. Multi-Sector, community-driven partnerships: An intentional strategy to advance health equity. NAM Perspectives. Commentary, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/202510a.

https://doi.org/10.31478/202510a

Helen Mittmann, MAA, is Senior Research Associate, Funders Forum on Accountable Health. Anne Morris Reid, MPH, is Policy Director, Funders Forum on Accountable Health. Jennifer Trott, MPH, is Principal Investigator, Funders Forum on Accountable Health.

Helen Mittmann, Anne Morris Reid, and Jennifer Trott report grants from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, The California Endowment, Episcopal Health Foundation, W.K. Kellogg Foundation, Kresge Foundation, Blue Shield of California Foundation, and a sponsorship from Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina Foundation.

Lisa Fujie Parks, Associate Program Director at the Prevention Institute; Aristea Saulsbury, Co Executive Director at the McKinleyville Family Resource Center; and Alison Poulsen, President of Better Health Together, provided valuable support for this commentary.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily of the authors’ organizations, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies). The paper is intended to help inform and stimulate discussion. It is not a report of the NAM or the National Academies. Copyright by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Related Perspectives