Alina Baciu

Maggie Anderson

Olayinka Adedeji

Anisa Amiji

Dhruvi Banerjee

Taylor Berek

Alex Boldin

Morgan Crotta

JaNýa D. Brown

Aidan Deneen

Summer Ford

Vladimir Franzuela Cardenas

Sadie Gray

Alicyn Grete

Eleanor Grudin

Jadyn Hamer

Noelle Herrier

Jessica Hively

Manal Khalid

Urmi Kumar

Clare Mazzeo

Antonio Mercurius

Jaimee Miller

Mayuresh Mujumdar

Airyn Nash

Caleb Oh

Maya Porter

Kayla Randall

John Russell

Teresa Russell

Amanda Saikali

Stephanie Sawicki

Erika Shook

Matthew Villanueva

Brianna Watson

This discussion paper provides an overview of the eleventh annual District of Columbia (DC) Public Health Case Challenge,[1] a student competition held in 2024 by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) and the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement in the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies). The Case Challenge, which is both inspired by and modeled on the Emory University Global Health Case Competition,[2] is designed to promote interdisciplinary, problem-based learning in public health and foster engagement with local universities and their surrounding communities. The event brings together graduate and undergraduate students from multiple disciplines and local universities to promote awareness of and develop innovative solutions for 21st-century public health challenges experienced by communities in the District of Columbia.

Each year, the organizers work with a student case-writing team to develop a case based on a topic that is relevant to the DC area but also has broader national and, in some cases, global resonance. Content experts are recruited as volunteer reviewers of the case. Universities located in the Washington, DC area are invited to form teams of three to six students currently enrolled in undergraduate or graduate degree programs. To promote interaction among a variety of disciplines, the competition requires each team to include representation from at least three different schools, programs, or majors.

The case is released two weeks before the event and teams are charged to use critical analysis, interdisciplinary collaboration, and thoughtful action to develop a solution to the problem outlined in the case. On the day of the competition, teams present their proposed solutions to a panel of judges, composed of representatives from DC organizations and other subject matter experts. In 2024, a Grand Prize, an Interprofessional Prize, a Practicality Prize, and a Wildcard Prize were awarded.

2024 Case: A Public Health Approach to Address Substance Use and Mental Health Concerns among Emerging Adults in the DC, Maryland, and Virginia Area

The 2024 challenge aimed to address substance use and mental health concerns among emerging adults (18–29 years old) in the DC, Maryland, and Virginia (DMV) area. The case asked student teams to develop a proposal for a fictitious grant of $1.5 million over a three-year span.[3] The challenge required the teams to create an innovative, sustainable solution. The solution was expected to include a rationale and evidence base for the intervention, along with an implementation plan, budget, and evaluation strategy.

Background Information

Emerging adulthood, typically defined as aged 18–29 years old, is increasingly recognized as a critical and complex developmental period. It is marked by significant life transitions, including growing independence, identity exploration, and decisions related to education, career, and relationships (Davis et al., 2012). This stage also involves heightened risk-taking behaviors, substance use, and shifting from dependence to independence, which can contribute to stress, loneliness, and mental health challenges (Arnett et al., 2014; Davis et al., 2012).

Though brain development is nearly complete by this age—including maturation of the prefrontal cortex, which governs decision making—many emerging adults delay traditional markers of adulthood, such as marriage, homeownership, and parenthood (Arain et al., 2013; Davis et al., 2018). This delay can lead to confusion and disengagement from adult responsibilities. Mental health vulnerability is high, with 75 percent of lifetime mental health disorders emerging by the age of 24 (Halfon et al., 2018).

In addition to rising levels of stress and loneliness, common mental health issues in emerging adults include anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders (SUDs) (Office of the Surgeon General, 2023). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as family instability or abuse, can heighten the risk of mental health problems that persist in adulthood (CDC, 2021). Despite these risks, emerging adults often face limited access to mental health and substance use services (Arnett et al., 2014) Moreover, societal structures and public policies often overlook the specific needs of this age group, leading to disengagement from essential health supports (Sakala et al., 2020). Addressing these gaps and fostering resilience is critical to supporting a successful transition into adulthood.

Case Scenarios and Framework

The Case Challenge described these key issues through six fictional but realistic scenarios illustrating experiences of mental illness, substance use, and social isolation. Examples included a student in recovery seeking sober connections, a graduate student navigating cannabis use, and an international student experiencing culture shock and loneliness—each highlighting the need for accessible resources and social connection during this life stage.

Participating teams were also provided background on conceptual models and frameworks, including the dual-continuum model of mental health, social ecological model, social determinants of health, and the Okanagan Charter: An International Charter for Health-Promoting Universities & Colleges (Aronica et al., 2019; IHPCN, n.d.; ODPHP, n.d.; Westerhof and Keyes, 2010). The materials explored the impact of structural inequities and factors, such as housing, education, and physical and social environments. Additional content addressed the unique identities of college students, campus settings, and the intersections between mental illness and substance use. The background also included profiles of relevant local and national organizations dedicated to improving college student well-being.

Expert Perspectives

While the judges deliberated, student teams shared a three-minute overview of their solutions with one another, followed by a question-and-answer session. They also heard from two speakers: Alexandra Andrada Sliver of the National Academies and Deon Auzenne, a clinical psychology graduate student at Howard University. Their talks were followed by an engaging question-and-answer period with students.

Andrada Sliver spoke about the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, emphasizing that it is more than just a number. She provided historical context, noting that 911 took 60 years to reach its current level of public familiarity, and the goal for 988 is to achieve similar recognition much more quickly. Created by the National Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020, 988 Lifeline aims to provide a culturally competent, equitable, and accessible crisis response system. Staffed by trained crisis counselors, it prioritizes de-escalation, peer support, and suicide prevention, with an emphasis on addressing racial trauma, language barriers, and cultural competency (988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, n.d.). Challenges include long wait times, state-level variations, and limited public awareness. She also cited related National Academies work, including the Forum on Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders and its “988: It Is Not Just a Number” webinar series.[4]

Auzenne discussed the profound impact of financial stress, food insecurity, and housing instability on graduate student mental health, noting that graduate students are six times more likely to experience anxiety and depression. According to the 2023 Healthy Minds Survey, 41 percent of graduate students report moderate to severe depression (HMN, 2023). Auzenne defined flourishing as self-perceived success in areas such as relationships, self-esteem, purpose, and optimism—highlighting that it can coexist with mental illness. Only 36 percent of students report flourishing (HMN, 2023). Citing a study of 4,128 graduate students, Auzenne noted that nearly half of all Black students worried about food and housing—factors that are strong predictors of depression (Coffino et al., 2021). He emphasized that financial advocacy is essential to supporting mental health and described “decolonized psychology” as a model that frames justice as a form of healing. To promote institutional accountability, he suggested students join unions, participate in governance, petition for change, collaborate with faculty, and connect with alumni networks.

Team Case Solutions

The synopses, prepared by students from the seven teams that participated in the 2024 Case Challenge, describe the specific need identified by the teams within the broader topic area, how they formulated a solution to intervene, and how they would implement it if they were granted the fictitious $1.5 million allotted to the winning proposal (budgetary information is not included here). Team summaries are presented beginning with the winners of the Grand Prize (University of Maryland, Baltimore), followed by the Harrison C. Spencer Memorial Interprofessional Prize winners (Howard University), the Practicality Prize winners (The George Washington University), and the Wild Card Prize winners (American University), with the remaining team summaries provided in alphabetical order by institution.

University of Maryland, Baltimore: Guiding Resilience and Offering Wellness (GROW) at Community College

Team Members: Alex Boldin, JaNýa D. Brown, Amanda Saikali, and Erika Shook

Summary prepared by: Alex Boldin, JaNýa D. Brown, Amanda Saikali, and Erika Shook

Faculty Advisors: Greg Carey, Byron Cheung, Sara Devaraj, and Rebecca Hall

Background and Statement of Need

Emerging adulthood is a high-risk period for mental health and substance use, marked by identity exploration, instability, and the assumption of adult responsibilities (Munsey, 2006; UNH, n.d.). National data show that young adults aged 18–25 have the highest rates of mental illness and SUDs among all adult age groups (NIAAA, 2025; SAMHSA, 2021), with 46 percent of college students reporting a lifetime mental health diagnosis in 2022–2023 (HMN, 2023).

For students in community colleges (CCs), these risks are even greater. CCs enroll many students from marginalized populations, who are already at higher risk, including students of color, first-generation students, low-income students, and single parents (Horn and Nevill, 2006). These students often experience financial hardship, lower familial support, and significant nonacademic responsibilities while attending institutions with fewer mental health resources than four-year colleges (Lipson et al., 2021).

The result is a population facing higher rates of depression, anxiety, and substance use but with lower access to mental health care (Lipson et al., 2021). Limited financial resources and low awareness of available services prevent many CC students from seeking support, and institutional resources remain limited (Lipson et al., 2021). Additionally, CC students receive less education on key mental health topics, such as substance use, stress management, and sexual assault (Katz and Davison, 2014). These overlapping vulnerabilities highlight the urgent need for targeted, accessible interventions that address the specific mental health and substance use challenges faced by CC students. Furthermore, mental health services are increasingly becoming the most decisive factor among students choosing a college and remain a top concern for educators (Clark and Taylor, 2021; Flaherty, 2023). Investing in wellness initiatives, such as Guiding Resilience and Offering Wellness (GROW), is in the best interest of institutions seeking to support student success.

Goals and Intended Outcomes

GROW is a comprehensive support system designed to enhance CC students’ well-being through direct case management, peer engagement, and innovative mental health outreach. It seeks to strengthen CC infrastructure to ensure its effective and sustainable integration within campuses. In the long term, GROW aims to reduce substance use and mental health risks by fostering a supportive and responsive academic environment that provides the resources and skills needed to navigate wellness effectively.

GROW is designed to increase awareness and use of mental health resources both on and off campus, improve access to care for students facing financial and systemic barriers, enhance mental and health literacy, and create a culture shift that empowers students to engage with wellness more openly.

Intervention—Three Core Components of GROW

Case Management Services

Navigating and securing health coverage is often challenging, particularly for CC students who lack access to university-sponsored health insurance and often face additional barriers, such as work and family obligations. To address this, two dedicated case managers will be trained to help students navigate health care coverage and identify affordable mental health services, connect students with campus and community-based resources, and offer individualized guidance to remove financial and logistical barriers to care.

Interactive Screening Program

Developed by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the Interactive Screening Program is an evidence-based, anonymous online tool that connects students to mental health services. It is particularly effective for students reluctant to engage with traditional care models (AFSP, n.d.). Key features include anonymous online mental health screenings, personalized counselor outreach from campus mental health professionals, and a targeted advertising campaign to reduce stigma and increase student participation.

Wellness Leadership Workshop and Certification Program

This three-tiered workshop series is designed to enhance mental health literacy (MHL), foster community engagement, and develop leadership skills among CC students. Participants earn certifications at the completion of each level.

Level 1. MHL and Peer Support: Students begin with MHL training to recognize, understand, and address mental health issues. The peer support programs are utilized to reduce stigma and increase referrals to mental health services (Kalkbrenner et al., 2020). Students are also taught the REDFLAGS model to help identify warning signs, like class absences and emotional distress, helping guide peers toward appropriate resources (Kalkbrenner et al., 2021).

Level 2. Community and Engagement Services: Students apply their MHL training through service projects with local organizations. Reflection sessions follow each project, reinforcing personal and community impact. This community involvement reduces isolation, strengthens social bonds, and encourages prosocial behaviors (Smith et al., 2014; Wray-Lake et al., 2012). Engagement in structured service activities has been linked to lower substance use rates (Collinson and Best, 2019).

Level 3. Leadership Development and Campus Advocacy: Students build leadership skills to promote mental health awareness and policy change. Peer-led training models reinforce MHL skills and encourage sustainable peer support networks. Students engage in campus-wide initiatives, empowering them to shape supportive campus cultures (Kalkbrenner et al., 2020, 2021; Kalkbrenner and Sink, 2018).

Ultimately, the program’s leadership, policy, and service initiatives build upon one another to ensure long-term sustainability while addressing underlying sources of risk. The train-the-trainer workshop model creates a self-sustaining cycle of student leaders equipped with critical, long-term skills. By forging community ties through service and advocacy, GROW cultivates a mutually beneficial and lasting network of support.

Potential Barriers and Solutions

The recent and continued shift toward online education may pose a potential barrier to the success of the GROW program, with 60 percent of CC students taking at least one online course and 32 percent fully online in fall 2022 (CCRC, n.d.). This trend may limit enrollment in the workshop, which is designed to foster social connection and relies on in-person participation. One solution may be to include an online workshop option and gradually reduce reliance on in-person meetings, if necessary. However, the initial rollout will remain in person to encourage meaningful peer interaction. Another barrier may be limited student awareness of the campus resources, including GROW, which is a frequent and persistent issue among all college students but especially at CCs (Katz and Davison, 2014; Lipson et al., 2021). Thus, GROW will launch a comprehensive outreach campaign using physical materials (e.g., posters, brochures, and syllabus language) and digital promotion (e.g., website banners). Furthermore, professors will receive information about the program and be encouraged to highlight it in introductory materials (e.g., syllabi).

GROW will be evaluated using measurements of program use and impact. Annual campus-wide pretest surveys and post-test surveys for students who engage with GROW programming will be administered throughout the year. Data related to mental health needs and outcomes will also be collected and analyzed. A full-time data analyst will be hired to lead this program evaluation for GROW.

Howard University: Support. Equip. Enrich. Nurture. (S.E.E.N.)

Team Members: Summer Ford, Jadyn Hamer, Antonio Mercurius, and Brianna Watson

Summary prepared by: Summer Ford, Jadyn T. Hamer, Antonio Mercurius, and Brianna Watson

Faculty Advisors: Pamela Carter-Nolan and Monica L. Ponder

Problem and Background

On average, children in foster care are exposed to 2.5 ACEs (Turney and Wildeman, 2017). ACEs are linked to a higher likelihood of poor health, mental health challenges, and substance use outcomes in early adulthood (Mersky et al., 2013). Individuals who experience early life adversity have a higher frequency of alcohol and marijuana use in mid-adolescence and between the ages of 22 and 25 years old compared to those without such experiences (Mulia et al., 2025). Specifically, alcohol use increases in mid-adolescence and peaks at between the ages of 22 and 25 years old (Mulia et al., 2025). While the rate of binge drinking among individuals aged 18 to 25 years old is declining, 28.7 percent still engage in it (SAMHSA, 2024). The leading stressor contributing to binge drinking among 22–25-year-olds is financial strain (Leech et al., 2020).

Objective and Aim

The objective of the proposed solution, Support. Equip. Enrich. Nurture. (S.E.E.N.), is to support foster care community members who may have experienced ACEs that are strongly correlated to substance abuse. It aims to provide mental health and substance abuse support through community training, in-person support groups, a virtual community via a mobile app, and easily accessible emergency kits provided through vending machines.

Population of Interest

S.E.E.N. targets transition-aged foster youth (ages 18–25) in Washington, DC, specifically Black youth who are aging out or have aged out of the foster care system. In fiscal year 2024, 545 youth were in the system (DC CFSA, n.d.). By the end of the year, nearly 40 of them aged out, reflecting a broader trend in which 40 to 100 DC youth age out annually (Cuccia, 2023). Transition-aged foster youth are a growing subpopulation in DC and have been identified as a vulnerable group at increased risk for substance misuse and mental health challenges. (Phillips et al., 2024; SAMHSA, 2019). Furthermore, 94 percent of DC foster youth are Black or Hispanic, facing compounded risks due to racial and ethnic disparities in care (DC CFSA, n.d.; IOM, 2003b; SAMHSA, 2015, 2019). S.E.E.N. focuses on Wards 5, 6, and 7, where the highest concentration of foster youth resides, ensuring that interventions are culturally and environmentally attuned to the needs of this population.

Underlying Theory and Rationale

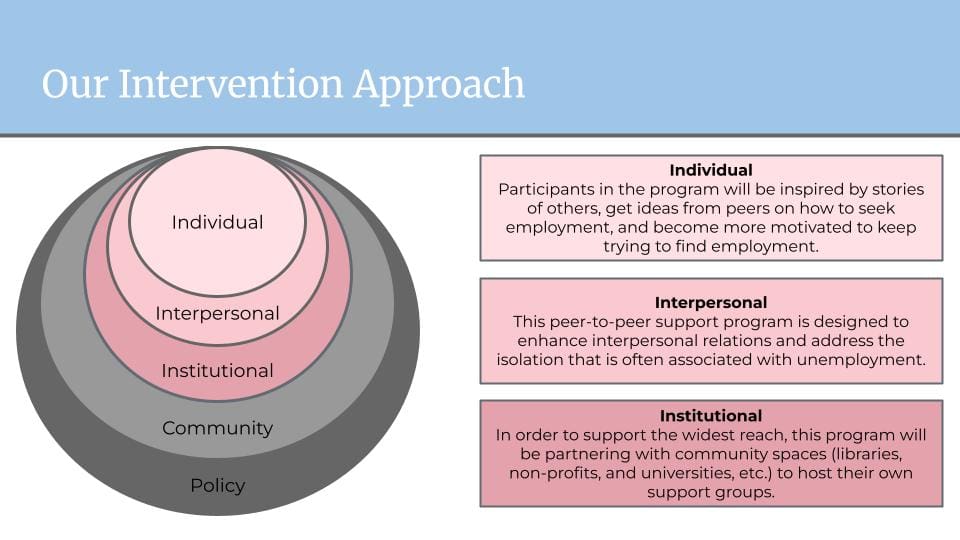

S.E.E.N.’s community center approach, grounded in the socioecological model, supports Black youth aging out of foster care through individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, and policy-level interventions.

- Individual level: A mobile app provides culturally sensitive resources for mental health and SUDs with a peer-matching system.

- Institutional level: DC recreation centers serve as safe spaces for mental health support and recreational activities.

- Community level: Vending machines that can easily be located by using the mobile app offer accessible, stigma-free supplies, such as hygiene products, mental health resource cards, and emergency supplies.

- Policy level: The initiative also advocates for policy changes to address systemic barriers and create a comprehensive, sustainable support system to empower youth aging out of foster care.

Strategy and Mechanism

S.E.E.N. will implement a three-pronged intervention: curriculum, vending (SEEN) machines, and a mobile app.

Curriculum: The curriculum, offered to community and recreation centers in DC, includes six training modules designed to help staff and volunteers: 1) understand shared experiences of these youth; 2) identify mental health and substance use trends; 3) recognize signs of crisis; 4) connect individuals to professional care; 5) provide resources and social support; and 6) advocate for policy protections. It also offers ongoing learning opportunities, such as roundtables, office hours, and expert-led webinars, to inform about emerging data and best practices.

SEEN Machine: The “SEEN” machine, inspired by Japan’s vending machine philosophy, emphasizes accessibility, variety, and community. Placed in partnership with community stakeholder organizations, it offers contactless access via the mobile app, which also tracks usage data. Key features include emergency batteries and digital settings that allow free distribution during disasters; visually appealing design to encourage engagement; and essential products, such as naloxone, snacks, electrolyte drinks, and first-aid supplies.

Mobile App: The mobile app enhances mental health service delivery by improving access and engagement, particularly for young adults. It provides 24/7 access to licensed counselors, ensuring around-the-clock support for guidance during distress or moments of need, and an embedded crisis hotline connecting users directly to the DC Access HelpLine for immediate assistance. It features a peer-matching system that connects users with mentors, peers, and professionals with shared backgrounds, reducing isolation. The app integrates with SEEN vending machines to provide essential products discreetly. It also links users to local resources, including in-person support, appointment scheduling, and recreational services. Empowering users to manage their health, the app combines digital tools with real-world assistance, aligning with research on the effectiveness of mobile health care apps (NIMH, 2024).

Potential Partners

S.E.E.N. aims to partner with local organizations and later expand to include recreational centers. Initial potential partnerships include the Foster and Adoptive Parent Advocacy Center, The DC LGBTQ+ Community Center, Best Kids, Inc., and Far Southeast Family Strengthening Collaborative. While S.E.E.N. plans to reach as many recreation centers as possible across DC, initial efforts will focus on Wards 7 and 8.

Big Picture

The S.E.E.N. solution is guided by three principles:

- Early mental health interventions improve long-term outcomes for these foster youth;

- Peer support and technology boost resilience, and leveraging technology (like the mobile app) create accessible mental health support; and

- Tailoring services to the unique needs of this population ensures culturally competent services.

These principles guide staff training, peer support networks, and the overall program design to effectively address mental health and substance use challenges.

George Washington University: The Third Space Collective: Loneliness as a Precursor to Alcohol Misuse and Worsening Mental Health

Team Members: Anisa Amiji, Taylor Berek, Morgan Crotta, Noelle Herrier, John Russell, and Stephanie Sawicki

Summary prepared by: Anisa Amiji, Taylor Berek, Morgan Crotta, Noelle Herrier, John Russell, and Stephanie Sawicki

Faculty Advisors: Karla Bartholomew, Jill Catalanotti, Sydnae Law, Gene Migliaccio, Ric Ricciardi, Sonia Suter, and Mary Warner

Background and Introduction

The 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) revealed that emerging adults in Washington, DC experience substantially higher rates of frequent drinking and binge drinking compared to the national average (SAMHSA, 2021). These statistics are particularly concerning for queer[5] emerging adults who, as of 2022, are nearly twice as likely to be at risk of alcohol use disorders compared to their cisgender heterosexual peers (Krueger et al., 2022). High rates of alcohol misuse among LGBTQ+[6] emerging adults, as highlighted by Fish and Exten (2020), reflect a dual burden of the general stressors of emerging adulthood compounded by oppression and discrimination tied to sexual and gender identity. For many queer individuals, substance use is not only a means of coping with stress but also a tool for exploring and affirming their identities, especially when they are challenging societal norms around gender and sexuality (Hunt et al., 2019). Alarmingly, a 2023 Trevor Project survey found that 57 percent of queer individuals experience loneliness—nearly double the rates of their cisgender, heterosexual peers (Trevor Project, 2023). In addition, queer individuals also experience significantly higher rates of depression and anxiety (Krueger et al., 2022). The pervasive loneliness and mental health disparity, exacerbated by systemic stigma and discrimination, are significant factors in an increased reliance on alcohol as a coping mechanism (Trevor Project, 2023). The metro area of Washington, DC has the seventh highest US population of LGBTQ+ individuals, with a substantial proportion of individuals aged 18–35 years old identifying as queer, including over 16,000 students (Cantor et al., 2020; Hanson, 2025). These findings underscore the urgent need for tailored interventions that not only address the distinct and chronic stressors faced by the LGBTQ+ community but also move beyond deficits-based models—those that narrowly emphasize dysfunction, risk, and adverse health outcomes—in favor of strengths-based frameworks that recognize and leverage resilience, identity pride, social support, and community connectedness as drivers of positive mental and physical health (Perrin et al., 2020).

The Third Space Collective’s Goal and Target Population

The primary goal of the Third Space Collective program is to empower queer first- and second-year students attending colleges and universities in the DC area by reducing loneliness, preventing alcohol misuse, and fostering social support through inclusive, substance-free spaces.

Intervention: Underlying Theory/Rationale

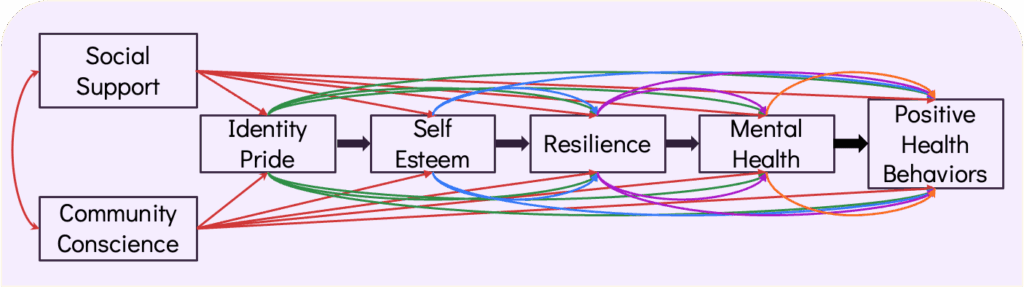

The minority strengths model (see Figure 1) highlights how personal and collective strengths within minority populations foster resilience and contribute to positive mental and physical health outcomes (Perrin et al., 2020). By moving away from a deficit-based approach, which risks reinforcing negative stereotypes, this model emphasizes the importance of building on the existing strengths of LGBTQ+ individuals and communities to create safe, alcohol-free spaces that celebrate identity, encourage community-building, and empower individuals to thrive while addressing the complex factors contributing to substance use.

Figure 1 | Minority Strengths Model SOURCE: Reproduced with permission from Perrin, P. B., M. E. Sutter, M. A. Trujillo, R. S. Henry, and M. Pugh, Jr. 2020. The minority strengths model: Development and initial path analytic validation in racially/ethnically diverse LGBTQ individuals. Journal of Clinical Psychology 76(1):118-136.

Strategic Objective 1: Establishing a Third Space

The first objective of the Third Space Collective is to cultivate an on-campus third space, as both a physical location and an online community, that prioritizes the LGBTQ+ community. The physical space will provide students of all sexual orientations and gender identities with 24/7 access to a safe environment and facilitate connections between students that are not centered around alcohol consumption. At this space, the Third Space Collective will host monthly skills workshops designed to improve students’ knowledge of the community resources that are available to them, including those specifically for queer individuals. The online community will use a chat platform (e.g., Discord), and is intended to maintain engagement with and accessibility of the resources provided by the collective.

Strategic Objective 2: Near-Peer Mentoring

The second objective is to engage with queer students through mentorship and discussions using the Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention of College Students (BASICS) program (DiFulvio et al., 2012). BASICS uses motivational interviewing techniques to educate and empower students who are at risk for alcohol misuse. The near-peer mentorship program will match participating first- and second-year undergraduates with graduate students and recent alumni who have participated in a brief BASICS training course (DiFulvio et al., 2012). The intended outcome is to increase participants’ awareness of tools to prevent alcohol misuse and provide connection to students who may be struggling.

Strategic Objective 3: Queer Empowerment Council

The third objective is to establish an elected body of undergraduate students to serve as the Queer Empowerment Council (QEC) and facilitate inclusion-focused training programs for faculty and staff. The QEC will work with leaders from the university to establish a continuous connection between university administrators and queer students so as to increase awareness of the specific needs of the queer community and collaborate to use the university’s resources to find solutions. The queer-inclusion-focused training will be given to university faculty and staff using the Advocates for Youth’s Safe Space Toolkit to provide the information and tools necessary to make the university overall a more inclusive space for the queer community (Butler, 2020).

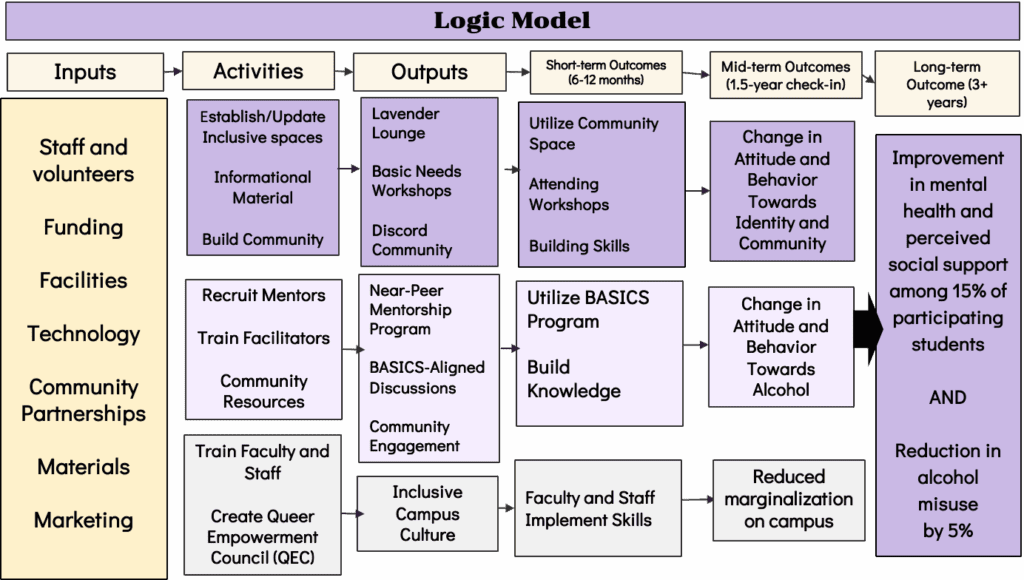

Outcomes

Through third spaces, near-peer mentorship, and faculty training, the program aspires to establish resilient support systems and set a new standard for inclusivity in higher education. Initial outcomes will be improved knowledge of coping skills and third space resources; participants will also gain awareness of the risks and consequences of alcohol misuse through BASICS and near-peer mentorship programs (DiFulvio et al., 2012). Additionally, goals include reduced loneliness scores for participants and increased awareness of queer inclusivity challenges on campus among faculty who attend training (Hughes et al., 2004). Additional goals include ongoing participation in all Third Space interventions, a reduction in binge drinking episodes (measured through anonymous surveys), and faculty and staff adopting at least two inclusive practices. Over three years, the Third Space Collective aims for a 15 percent improvement in mental health and social connectedness and a 5 percent reduction in binge drinking, as outlined in the logic model (see Figure 2).

Coordination with Stakeholders

Engaging stakeholders at every level is crucial to the success of this initiative. The program will work closely with deans, faculty, staff, LGBTQ+ organizations, and queer students to foster institutional support and create a campus culture that aligns with the collective’s mission. Feedback from the QEC will be integral to improving program strategies and ensuring that interventions remain relevant and impactful for the unique needs of each university. The Third Space Collective will partner with community-based organizations to ensure users have access to resources while off campus. Examples of community organizations include Booze Free in DC and Drug Free Youth DC (Drug Free Youth DC, n.d.; Silverman, n.d.). By coordinating with these diverse stakeholders, the Third Space Collective aims to build a robust network of support that empowers queer students to enhance protective factors, such as community connection and self-identity, and reduce alcohol misuse.

Figure 2 | Logic Model

SOURCE: Developed by George Washington University authors

Potential Barriers and Solutions

Implementing the Third Space Collective involves addressing key barriers through strategic measures. Recognizing the diversity within the queer community and emphasizing that queer individuals are not a monolith, the program will ensure that near-peer mentors reflect the diverse identities of the student population. Furthermore, the Third Space Collective uses “LGBTQ+” to better address the nuances of gender identity and reinforce its existence as entirely inclusive for all community members and allies.

To reduce bureaucratic hurdles, the QEC will engage with university leaders to streamline processes. Stigma and privacy concerns will be mitigated through a near-peer model that fosters trust and encourages an open, supportive dialogue. Sustaining engagement will be prioritized through clear time commitments, appreciation events, and annual QEC leadership rotations to prevent burnout. By embracing this multifaceted approach, the Third Space Collective aims to create an inclusive, empowering environment for all queer-identifying students on university campuses throughout Washington, DC.

American University: Developing Accessible Networks for Community Empowerment (DANCE) to Address Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Team Members: Aidan Deneen, Sadie Gray, Maya Porter, and Kayla Randall

Summary prepared by: Aidan Deneen, Sadie Gray, Maya Porter, and Kayla Randall

Faculty Advisor: Ali Chrisler

Background

Emerging adults in the Washington, DC metro area face significant challenges related to mental health and SUDs (SAMHSA, 2022). These issues are particularly concerning because they impact a critical developmental period, often leading to long-term consequences if left unaddressed (Spencer et al., 2021). According to Ahrens and colleagues (2014), any mental illness (AMI) refers to any mental, emotional, or behavioral disorders experienced within the past year that meet the diagnostic criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Mental health challenges in this age group often intersect with substance use, further compounding the difficulties faced by young individuals striving to lead stable and productive lives (Spencer et al., 2021).

SUDs, as defined by the DSM-5, involve problematic patterns of alcohol or drug use that increase the susceptibility to significant impairment and interfere with daily functioning, despite negative consequences (Spencer et al., 2021). SUDs can exacerbate existing mental health conditions, creating a cycle of dependency and distress (Spencer et al., 2021). Addressing these interconnected issues requires innovative and targeted interventions to prevent and manage AMI and SUDs among this vulnerable population, fostering resilience and promoting healthier life trajectories (SAMHSA, 2022).

Target Population

Members of the LGBTQ+ community experience mental health challenges and SUDs at significantly higher rates compared to the general population (Jones et al., 2020). During adolescence, LGBTQ+ youth face increased levels of stigma, discrimination, and victimization, leading to significant mental health challenges (Chang et al., 2021; Myers et al., 2020). Additionally, family rejection and lack of acceptance can lead to increased rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality (Miller et al., 2020; Pariseau et al., 2019).

Data from the SAMHSA (2022) NSDUH further underscore these disparities as LGBTQ+ youth enter adulthood. The data indicated that LGBTQ+ individuals were at least two times more likely to experience both any AMI and SUDs within the past year compared to their heterosexual counterparts.

Addressing these challenges requires comprehensive and culturally relevant efforts to reduce societal stigma, promote family and community acceptance, and provide accessible, culturally competent mental health services tailored to the unique needs of LGBTQ+ individuals. These strategies are essential to mitigate the effects of systemic barriers and foster resilience within LGBTQ+ populations.

Needs Assessment

While conducting a needs assessment with Sasha Bruce Youthworks, a DC-based organization that supports youth experiencing housing insecurity, a gap was identified in the services available for LGBTQ+ emerging adults struggling with substance use. To support the unique needs of this population, dance and movement therapy (DMT) was explored as a possible innovative solution. In one meta-analysis, DMT was investigated as a complementary approach and found to decrease depression and anxiety while increasing quality of life and interpersonal and cognitive skills (Koch et al., 2019). Although this study did not focus exclusively on individuals with SUDs, the findings indicate that DMT can be beneficial for mental health, which is often a critical component of SUD recovery. While direct evidence on the effectiveness of DMT specifically for SUDs is limited, these studies highlight its potential as a supportive therapy in addressing the complex interplay of mental health challenges and substance use.

To ensure the proposed DMT program was culturally relevant and fostered a safe and affirming space for all self-expression and community connections, Washington, DC’s rich ballroom culture was drawn upon—a vibrant subculture within the Black and Latinx LGBTQ+ community that serves as a critical source of belonging, especially for those who experience rejection from their peers due to their sexual orientation, gender identity, or race (Miller et al., 2020). Ballroom culture centers on events, referred to as “balls,” where individuals (or “houses”) compete in various categories that showcase fashion, performance, dance, and creativity. Participants often perform voguing—a dynamic dance style characterized by angular, fluid, and dramatic movements inspired by fashion poses. By integrating components of ballroom culture, the DMT program honors the long-lasting traditions of the LGBTQ+ community by encouraging resilience and identity affirmation.

Proposed Intervention

Developing Accessible Networks for Community Empowerment (DANCE) is an initiative that brings an innovative and community-centered approach rooted in the socioecological model (see Figure 3) to address mental health and substance use recovery for queer emerging adults within the DC metro area (Lee et al., 2017). DANCE integrates both art and dance therapy with behavioral interventions for treating young LGBTQ+ adults struggling with substance abuse and mental health and draws upon the theory of planned behavior. It is first and foremost community-centered, with the goal of engaging participants through culturally affirming, trauma-informed practices rooted in local queer history. Second, it combines art and movement to create therapeutic outlets for recovery and emotional healing. Last, a multilevel impact strengthening personal recovery, fostering a positive and uplifting community, and challenging societal stigmas is central to this initiative.

Figure 3 | Application of the Socio-Ecological Model to the DANCE initiative SOURCE: Reproduced with permission from Safe States Alliance. 2019. Strategies to Address Shared Risk and Protective Factors for Driver Safety. Available at: https://www.safestates.org/general/custom.asp?page=SRPFSEM (accessed June 20, 2025).

The DANCE initiative incorporates the socioecological model to address the stigma around queer identities and substance use by connecting recovery services to the Washington, DC queer community. It integrates the theory of planned behavior model by fostering a nonjudgmental, positive attitude toward recovery through dance and art therapy practices. The peer support, along with LGBTQ+ partnerships, cultivates a culture of empowerment. Building this sense of agency will encourage participants to intentionally engage in dance and art therapies, resulting in increased commitment in their recovery journey.

Evaluation Plan

The evaluation plan for DANCE combines both process and outcome evaluations to ensure its effectiveness in addressing SUDs and improving mental health among LGBTQ+ emerging adults.

The process evaluation focuses on monitoring the implementation of the program, including session attendance, engagement levels, and feedback from participants and facilitators. This will be conducted by clinicians and project managers throughout the program to assess whether activities, such as biweekly therapy sessions, outreach efforts, and community events, are being executed as planned. The data collected will help identify areas for improvement and ensure that the program remains aligned with its goals of providing accessible, culturally competent, and trauma-informed care.

The outcome evaluation aims to measure the program’s impact on participants’ recovery and overall well-being over time. This includes tracking key metrics, such as reductions in substance use, improvements in mental health, and enhanced social connectedness. An external evaluation consultant will analyze attendance data, participant surveys, and behavioral health assessments at various intervals, including three months, one year, and five years.

Long-term goals include sustained recovery, expansion of the program to other locations, and measurable reductions in mental health disparities among LGBTQ+ emerging adults. This comprehensive evaluation approach ensures that the DANCE program is both effective and adaptable, providing critical insights for scaling its impact and fostering long-term community resilience.

George Mason University: ThriveFirst

Team members: Vladimir Cardenas, Jessica Hively, Manal Khalid, and Jaimee Miller

Summary prepared by: Vladimir Cardenas, Jessica Hively, and Jaimee Miller

Faculty Advisors: Eman Elashkar, Debora Goldberg, and Evelyn Tomaszewski

Background

The population of first-generation college students, referred to as “first gen,” is defined as those whose parents did not complete a 4-year degree (FirstGen Forward, n.d.a). In Washington, DC, 34.59 percent of undergraduate students identify as first gen (Hamilton and Beagle, 2023). First gen students are less likely than continuing-generation college students to access mental health treatment. Their unique sets of challenges, such as financial barriers, familial expectations/guilt, and lack of coping skills, all contribute to them being less likely to access mental health treatment (Lipson et al., 2023).

Proposed Solution

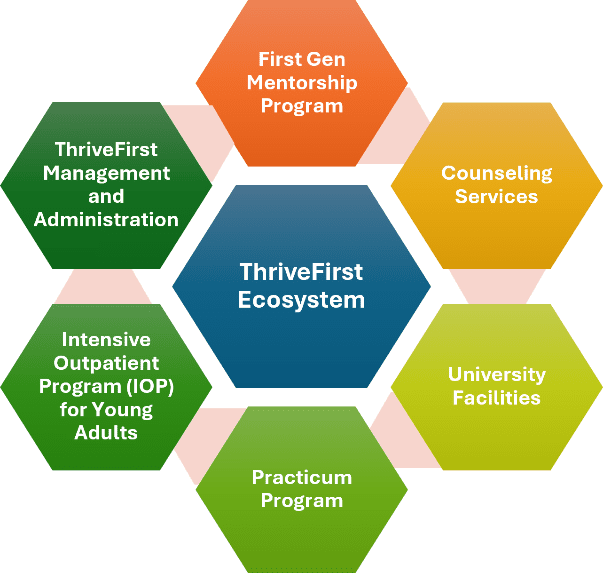

ThriveFirst is a stepped care model with a collaborative approach to support first gen students (Campus Mental Health, n.d.). They can advance through the steps to access comprehensive mental health support. Step 1 involves promoting a partnership between university counseling centers and first gen organizations on two college campuses in Washington, DC focused on outreach, education, prevention, and referral. Step 2 involves outpatient treatment at the university counseling center. Step 3 has that center partnering with a local hospital system that already offers an emerging adult intensive outpatient program (IOP) with nine hours of programming per week for 30–90 days, including individual and group therapy. ThriveFirst would implement an innovative solution for IOP by partnering with the hospital system to bring it to campus to eliminate barriers such as transportation and offer programming at times that work with a college student’s schedule. This solution was inspired by a current program at Texas Christian University that brings IOP to campus (Campus Mental Health, n.d.; TCU, n.d.; Wood, 2022). ThriveFirst would offer copay and deductible subsidies to ensure students who need IOM can afford it. Step 4 is for students whose needs cannot be met by the university counseling center and involves offering referrals to specialized treatment, such as substance use disorder or eating disorder treatment, inpatient hospitalization, and case management services.

Implementation Plan

ThriveFirst will be implemented in two DC universities that meet the following criteria: 1) offer 4-year undergraduate degrees, 2) require student health insurance, 3) are a FirstGen Forward institution that follows a national model for holistic first gen success (FirstGen Forward, n.d.c), and 4) have a counseling center. ThriveFirst will select a partner hospital that offers an IOP for emerging adults, which will provide IOP on campus and training for the university’s graduate health professional students to support the development of the next generation of mental health professionals and offer further incentive for universities to host the IOP. ThriveFirst will establish a strategic partnership ecosystem (see Figure 4) within each university that works together to help address mental health concerns for first gen students.

Figure 4 | ThriveFirst Ecosystem

SOURCE: Developed by George Mason University authors

Evaluation Plan

ThriveFirst will measure clinical, student, and program outcomes to ensure success. Clinical outcomes will be measured using the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms pre- and postintervention (Campus Mental Health, n.d.). Student outcomes will be measured using university graduation and attrition rates. Program outcomes will be measured by surveys of first gen engagement, number of referrals from the first gen organizations to the university counseling center, IOP attrition rates, and use of the insurance subsidy support.

Georgetown University: PeerForward: Finding Hope Through Community

Team Members: Olayinka Adedeji, Dhruvi Banerjee, Eleanor Grudin, Clare Mazzeo, and Caleb Oh

Summary prepared by: Olayinka Adedeji, Dhruvi Banerjee, Eleanor Grudin, Clare Mazzeo, and Caleb Oh

Faculty Advisors: Oliver Johnson and Ruiling (Sophie) Zou

Peer Forward

In August 2024, Washington, DC recorded the highest unemployment rate in the United States, with Wards 7 and 8 bearing the brunt of this crisis (DC.gov, n.d.b). Unemployment among emerging adults (ages 19–29) has been closely linked to heightened rates of depression (23 percent), substance use (14 percent), and loneliness (40 percent) (Compton et al., 2014; DC.gov, n.d.b). These numbers are particularly concerning for emerging adults who are Black, former foster youth, or involved in the juvenile justice system, who already face social isolation, and significant health disparities (Arain et al., 2013; Kennedy et al., 2023; Zhong et al., 2018). Amid these challenges, the pressing need for a community-based intervention became evident (NAMI DC, n.d.).

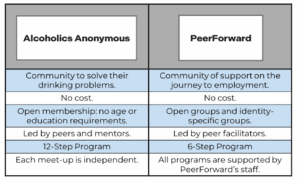

To address this gap, PeerForward will implement peer-led support groups modeled after the structure and peer-accountability approach of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) (see Figure 5). However, unlike the traditional 12-step program, these groups are specifically tailored for individuals grappling with unemployment and related mental health and substance use challenges (Peterson et al., 2008). The target audience includes Black emerging adults in Wards 7 and 8, former foster youth, and youth recently involved with the juvenile criminal legal system. By adapting proven principles of support group facilitation, PeerForward offers a space that normalizes conversations around unemployment, depression, and substance use, aiming to dismantle the stigma often associated with them (Nickell et al., 2020).

Figure 5 | Model Comparison Between Alcoholics Anonymous and PeerForward SOURCE: Developed by Georgetown University authors

The AA and PeerForward models similarly provide a community space at no cost to the individual and allow all to join. PeerForward expands on the AA model by providing education training to group facilitators, adopting a six-step model, and supporting all group events.

Key Program Features

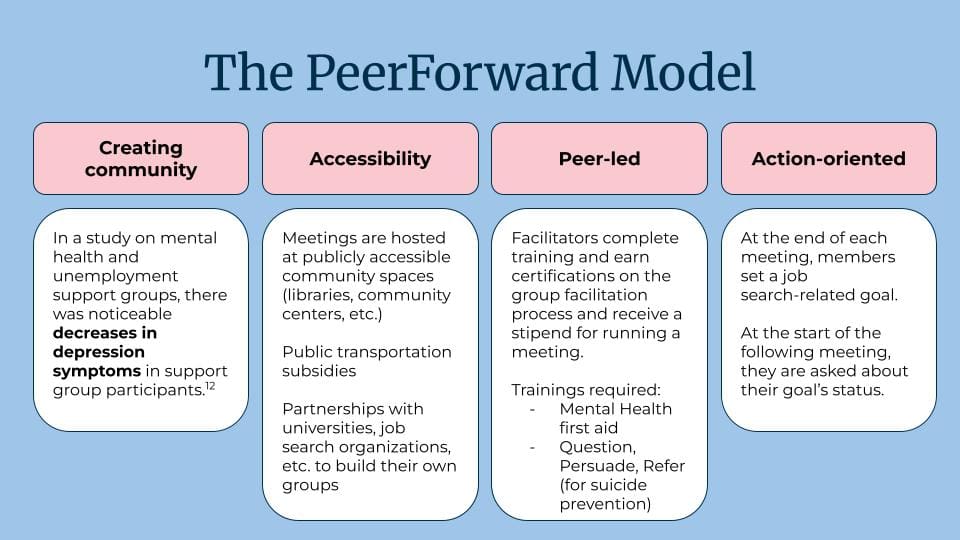

At its core, PeerForward is designed to be accessible, sustainable, and community driven (see Figure 5). Meetings will be hosted in publicly accessible locations, such as libraries and community centers, supplemented by transportation subsidies to ensure that distance and cost do not hinder participation. Peer facilitators will be compensated and trained to deliver mental health first aid and question, persuade, refer suicide prevention. With this training, they will guide conversations, foster mutual encouragement, and maintain an environment where participants feel supported and accountable to one another. By integrating group reflections, goal setting, and peer mentorship, the program will cultivate a resilient network that empowers participants to move forward in their personal and professional lives.

Figure 6 | The PeerForward Model Four Pillars SOURCE: Developed by Georgetown University authors

The PeerForward model aims to adhere to the four pillars (Figure 6) of creating community for those experiencing unemployment, creating accessible meetings, hiring trained and certified peer leaders, and providing action steps to those dealing with employment.

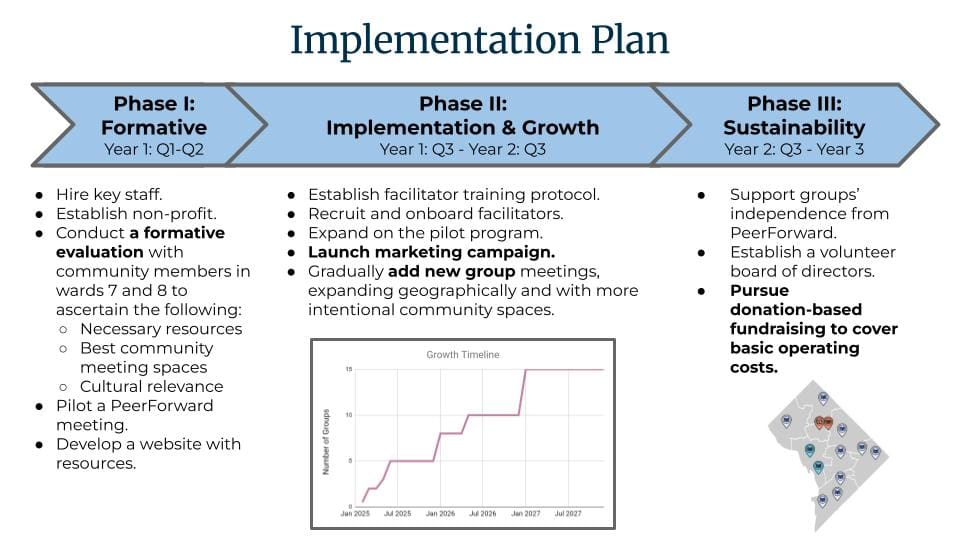

Implementation Approach

Implementation will occur in three phases (Figure 7). During the formative stage (Year 1, Quarters 1–2), PeerFoward will engage community members, conduct needs assessments, pilot initial meetings, and recruit facilitators. The data and feedback from this phase will help refine the meeting structure and curriculum. Moving into the implementation phase (Year 1, Q3–Year 2, Q3), the program will expand into additional venues across Wards 7 and 8. Outreach campaigns carried out through partnerships with local organizations (Figure 8) and a modest marketing strategy, will build awareness and bolster participation (SADD, n.d.). Finally, the sustainability phase (Year 2, Q3–Year 3) will lay the groundwork for long-term success through volunteer-led governance, fundraising initiatives, and formal mentorship programs that match individuals who have completed the program with newcomers.

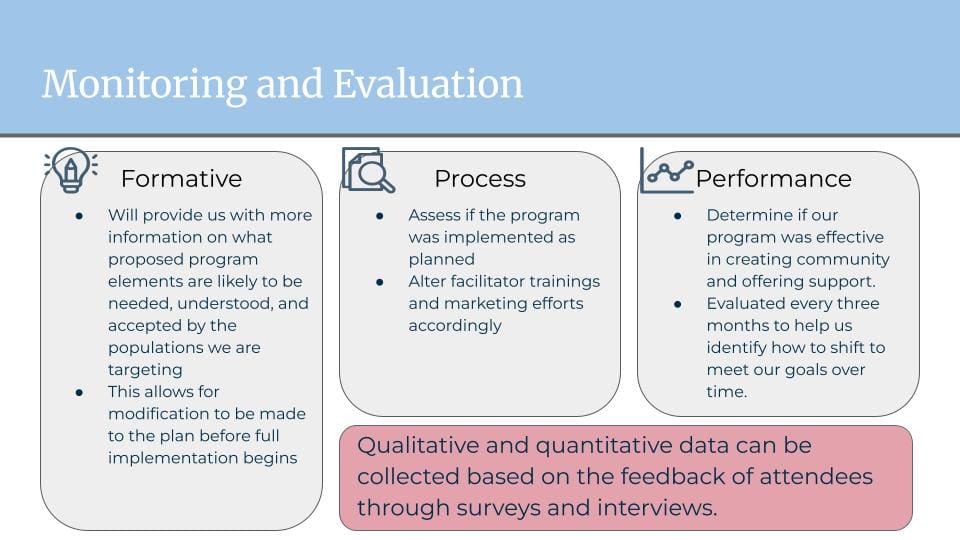

Monitoring and evaluation of the program will be ongoing to provide feedback on attaining the set goals (Figure 9). Every three months, participants and facilitators will be invited to provide feedback through interviews, surveys, and group discussions. These methods will help identify strengths and areas needing refinement, ensuring that the program is focused on reducing stigma and providing meaningful, tangible support to those who need it most.

Figure 7 | Implementation Timeline Projection for PeerForward

SOURCE: Developed by Georgetown University authors

Phase I is the formative phase, where staff will be hired and a pilot meeting conducted. Phase II focuses on expanding facilitator training and launching marketing materials to advertise the new groups forming in different wards. Phase III is concerned with finding sustainable funding to continue the program.

Figure 8 | PeerForward Proposed Monitoring and Evaluation Plan

SOURCE: Developed by Georgetown University authors

The monitoring and evaluation plan consists of formative, process, and performance evaluation to provide feedback during each implementation and expansion phase of the program. Surveys and interviews with attendees will provide data for these evaluations.

Budget and Partnerships

The financial plan includes salaries and benefits for key staff, such as an executive director and a community relations manager, along with part-time staff dedicated to marketing and fundraising. Equally critical are stipends for peer facilitators, who will be on the front lines of running meetings and guiding participants through challenges. The budget also factors in transportation subsidies—recognizing travel as a potential barrier—and meeting refreshments to encourage attendance and a welcoming atmosphere. Marketing efforts will include ads on public transit, community posters, and social media outreach. Strategic collaborations with local universities, job search organizations, and mental health resources will strengthen the support network and support a holistic approach to mental health and career guidance (SADD, n.d.). The long-term goal is to eventually become self-sustaining through small fundraisers to support facilitators’ stipends.

Anticipated Outcomes

The PeerForward program’s short-term goals are to reduce loneliness, mitigate the stigma of unemployment, and expand access to both emotional support and practical resources. Over the long term, PeerForward will evolve into an enduring program that fosters community cohesion, supports mental health, and equips emerging adults with the confidence and tools to navigate pathways to stable employment. PeerFoward aims to create a sustainable solution driven by those who need it the most. By empowering participants as both recipients and providers of peer support, PeerForward aims to not only lift the burden of unemployment but also to spark a broader culture of mutual aid and shared hope within Wards 7 and 8—and potentially beyond (see Figure 9 for the PeerForward social ecological model).

Figure 9 | PeerForward Social Ecological Model SOURCE: Developed by Georgetown University authors

The PeerForward program would make visible impacts at the individual, interpersonal, and institutional parts of the social ecological model.

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: LEVEL UP: A Gamified App Connecting DC Organizations to Support Emerging Adult Mental Health

Team members: Alicyn Grete, Urmi Kumar, Mayuresh G. Mujumdar, Airyn J. Nash, Teresa L. Russell, and Matthew Villaneuva

Summary prepared by: Alicyn Grete, Urmi Kumar, Mayuresh G. Mujumdar, Airyn J. Nash, Teresa L. Russell, and Matthew Villaneuv

Faculty Advisors: Weyinshet Gossa, John Hatfield, and Bolanle Olapeju

Background

Low-resource emerging adults are at higher risk for mental health and SUDs compared to their peers (AHR, 2023). Key contributing factors include poor coping strategies, social stigma, perceived social isolation and loneliness, and impaired access to resources (AHR, 2023; APA, 2024a, 2024b; Cohen Veterans Network and NCBH, 2018; Hill, 2024; Moritz et al., 2016; Nieto et al., 2020). Studies found a negative correlation between both age and maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as substance or alcohol use and avoidance behaviors (Metzger et al., 2017; Moritz et al., 2016; Nieto et al., 2020). Additionally, a survey found that young adults are more likely to fear judgment for seeking mental health care (49 percent Gen Z and 40 percent millennials compared to 20 percent Gen X and boomers), struggle to find mental health services (31 percent Gen Z and 32 percent millennials compared to 20 percent Gen X and 13 percent boomers), and rely on unreliable information sources (45 percent Gen Z and 41 percent millennials compared to 28 percent Gen X and 19 percent boomers) (Cohen Veterans Network and NCBH, 2018). Furthermore, 30 percent of young adults report feeling lonely every day or several times a week (compared to 10 percent in all ages), and 70 percent cite social connection as the biggest factor contributing to their mental health (APA, 2024a, 2024b). Research also indicates that emerging adults have lower retention rates for mental health services after their initial visit (Colizzi et al., 2020).

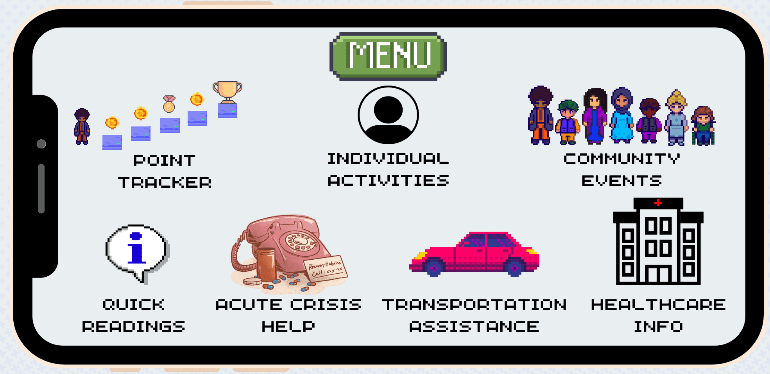

Figure 10 | Level Up Interface Mock-up

SOURCE: Developed by the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences authors

Goals

Level Up aims to improve mental health and reduce substance use among vulnerable emerging adults in Washington, DC through a gamified, app-driven mental health tool (Figure 10). The program targets knowledge gaps related to negative-coping, stigma, social isolation, and resource accessibility, fosters engagement with mental health resources, and encourages habit formation around adaptive behaviors, such as mindfulness, substance-free socialization, and help-seeking, that support long-term well-being.

Intended Outcomes

This intervention intends to improve mental health and reduce substance use by fostering community engagement, consolidating available resources, and reinforcing positive behaviors.

Objective 1: 70 percent of participants will attend monthly DC community-building activities to promote substance-free socialization and expand social networks throughout the intervention period.

Objective 2: 20 percent of participants will access consolidated resources (e.g., transportation assistance, telehealth options, and funding for necessary participation materials), improving access to mental health and substance abuse reduction services.

Objective 3: 20 percent of participants will remain actively engaged in the program, reinforcing habitual community participation and sustained mental health improvements, leading to substance use reduction.

Intervention Details

Target Population

The program targets three low-resource groups of emerging adults in Washington, DC: first-generation Pell grant awardees (aged 18–24) at DC universities, justice-involved emerging adults (18–29), and older emerging adults (aged 25–29) in academia or transitioning into the workforce (Deal et al., 2022; Ekers et al., 2014; FirstGen Forward, n.d.b; Hanson, 2024; JPI, 2020; Schiraldi et al., 2024).

Rationale/Theory

This intervention is grounded in behavioral activation, gamification, and positive reinforcement principles proven effective in similar mental health programs (Cheng and Ebrahimi, 2023; Ekers et al., 2014; Gardner et al., 2012; Janssen et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2016; Judah et al., 2018; Psychology Today, 2023; Scott et al., 2023; Wang and Feng, 2022; Zorbas, 2023).

Behavioral activation involves increasing engagement in meaningful activities to improve mood and reduce avoidance behaviors (Ekers et al., 2014; Janssen et al., 2020; Psychology Today, 2023; Wang and Feng, 2022). Gamification applies game-like elements (e.g., rewards, challenges, and progress tracking) to enhance motivation and user engagement (Cheng and Ebrahimi, 2023; Johnson et al., 2016). Positive reinforcement strengthens desired behaviors by providing rewards or incentives, encouraging sustained participation in mental-health-promoting activities (Judah et al., 2018; Scott et al., 2023; Zorbas, 2023). This program aligns with the socioecological model (McLeroy et al., 1988) across five levels:

- Individual Level: Encourages mental wellness habits through habit tracking.

- Interpersonal Level: Fosters peer support, reducing stigma and encouraging social connection through joint event attendance.

- Institutional Level: Partners with private and public institutions to centralize and enhance resource access.

- Community Level: Focuses on engagement in substance-free events, reinforcing positive social activities.

- Policy Level: Aligns with national initiatives and incorporates advocacy efforts for systemic change.

Program Structure

This intervention centers on a gamified app where participants earn points by completing individual mental wellness activities (e.g., daily mindfulness, physical exercise), attending local community events (e.g., cultural food nights, volunteering), or using mental health education or health care resources. Points are tracked through in-app scanning of QR codes at events and in-app metrics for the individual activities and can be exchanged for rewards, such as small gift cards, or as raffle entries for large prizes (e.g., sporting event tickets). Community event participation is allotted more points due to the ease of tracking and focus on community engagement. This focus targets the principle of behavioral activation, to help associate community activities without substance use with positive emotions (Ekers et al., 2014; Janssen et al., 2020; Psychology Today, 2023; Wang and Feng, 2022). The gamified points system is designed to increase motivation and engagement and provide positive reinforcement to create and maintain good habits (Cheng and Ebrahimi, 2023; Gardner et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2016; Judah et al., 2018; Scott et al., 2023; Zorbas, 2023).

Potential Partners

The program seeks public- and private-sector partnerships for event cosponsorship, hosting, and/or rewards (Bazron, 2023). Proposed public-sector partners include the Library of Congress, Smithsonian Institution, DC Public Libraries, DC Department of Behavioral Health, and the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (e.g. DC Metro) (DC.gov, n.d.a; DC Public Library, n.d.; Hayden, n.d.; Smithsonian, n.d.; WMATA, n.d.). Proposed private-sector partners included DC universities, DC professional sports teams (e.g., Washington Nationals), DC Run Clubs (e.g., DC Front Runners), DC Psychological Association, Something Different DC, the Faunteroy Center, Uber, and Lyft (DC Front Runners, n.d.; DCPA, n.d.; FH Faunteroy Center & Resilience Incubator, n.d.; Lyft, n.d.; Something Different DC, n.d.; Uber, n.d.; Washington Nationals, n.d.). Stakeholders across multiple organizations have confirmed the feasibility and acceptability of this program in personal conversations with the team.

Potential Barriers and Solutions

Despite enthusiastic stakeholder support, a potential barrier will be gaining the trust and buy-in of the target population. The app platform is designed to be most appealing and accessible to them; however, there is a risk of the app being downloaded and unused as participants begin the intervention. Therefore, boosting buy-in is critical until habitual behavior changes occur.

Monitoring and Evaluation

To assess program impact, the app will track user engagement with key intervention components according to the following objectives. Monitoring data will be provided through deidentified app engagement tracking data monthly and annually.

- Community Participation (Objective 1): Attendance at community-building activities will be monitored to evaluate the program’s impact on social network expansion and substance-free socialization.

- Resource Utilization (Objective 2): User interaction with consolidated resources (e.g., transportation assistance, funding support) will be tracked to assess accessibility improvements.

- Long-term Engagement (Objective 3): Finally, to encourage habitual involvement in community activities to reduce substance use and support mental health, retention of active users will be measured over 12 months to evaluate sustained participation and its effects on mental health and substance use reduction.

Conclusion and Reflections

The solutions presented by competing teams in 2024 revealed several recurring themes and highlighted the use of varied strategies. Common themes included the need for consistent support structures, innovative outreach mechanisms, and new settings to engage emerging adults in an increasingly complex technological landscape. Teams also emphasized the importance of fostering deeper human connections in novel ways. Many focused on specific populations with distinct needs and circumstances, such as community college students and young adults transitioning out of foster care.

Several teams emphasized the importance of understanding the specific barriers individuals face in accessing services and the need for involvement from external stakeholders, community leaders, and those with lived experience. This inclusive approach was viewed as essential for ensuring that interventions are both relevant and impactful.

The value of peer support and community networks was a recurring theme. Many teams highlighted the importance of building supportive environments that foster trust and reduce isolation. Peer-led strategies were seen as particularly effective in creating shared understanding and mutual support. However, several teams also called for a stronger emphasis on skills development, training, and pathways for long-term success. Equipping individuals with practical tools and resources was seen as key to addressing immediate challenges but also to fostering resilience and promoting future stability.

Clear and measurable outcomes were also identified as critical to program success. The judges underscored the need to refine evaluation strategies to ensure tracking both short-term progress and long-term impact. Strong evaluation practices were viewed as essential for adapting programs to evolving needs, demonstrating success, and securing sustained funding.

Finally, collaboration and cross-sector partnerships emerged as vital to program sustainability. Many teams proposed integrating interprofessional expertise and partnering with community organizations, educational institutions, and health care providers to expand the scope and reach of interventions. These collaborations were recognized for their ability to not only provide more comprehensive care but also enhance the credibility, resource base, and overall effectiveness of the programs.

By addressing these interconnected factors, the proposed solutions aim to create meaningful, enduring on the communities they aim to serve.

Future Plans

The Case Challenge links National Academies activities in health and medicine with both university students and the Washington, DC community. In 2025 the DC Public Health Case Challenge will continue, hosted by the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement, with the support of NAM’s Kellogg Health of the Public Fund (Kellogg Fund) and involvement from other groups in the National Academies, including the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education. National Academies staff continue to look for new ways to further involve and create partnerships with the next generation of leaders in health care and public health and the local Washington, DC community through the Case Challenge.

Case Challenge organizers will continue to provide information about the socioecological model of health (IOM, 2003a) and upstream (i.e., broad societal and distal to the individual) factors that affect health in the case document sent to the competing teams. This will help teams prepare for the event and encourage them to use these key elements in their solutions. Organizers will hold a webinar before the case is released to the competing teams to provide a primer on evidence-based policy solutions for public health issues. In 2024, an overview was provided to students by Alina Baciu, MPH, PhD, senior program officer and director of the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement. The webinar orients students to the Case Challenge, reviews best practices developed over the years, and then holds a question-and-answer period. It is recorded so that students have future access to it.

The organizers also hope to engage the competing teams and relevant DC stakeholders after the event to further explore solutions to the complex issues presented in the Case Challenge.

Join the Conversation!

![]()

New from #NAMPerspectives: Eleventh Annual DC Public Health Case Challenge: A Public Health Approach to Address Substance Use and Mental Health Concerns among Emerging Adults in the DC, Maryland, and Virginia Area. Read now: https://doi.org/10.31478/202509b

References

- 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. About 988 Lifeline. Available at: https://988lifeline.org/ (accessed August 19, 2025)

- AFSP (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention). n.d. Interactive screening program. Available at: https://afsp.org/interactive-screening-program/ (accessed June 12, 2025).

- AHR (America’s Health Ranking). 2023. Health equity in focus: Mental and behavioral health data brief. The United Health Foundation. Available at: https://assets.americashealthrankings.org/app/uploads/ahr_2023_mentalhealth_databrief_final2-web.pdf (accessed August 19, 2025)

- Ahrens, K. R., M. M. Garrison, and M. E. Courtney. 2014. Health outcomes in young adults from foster care and economically diverse backgrounds. Pediatrics 134(6):1067-1074. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-1150.

- APA (American Pyschiatric Association). 2024a. American adults express increasing anxiousness in annual poll; Stress and sleep are key factors impacting mental health. Available at: https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/news-releases/annual-poll-adults-express-increasing-anxiousness (accessed April 1, 2025).

- 2024b. New APA poll: One in three Americans feels lonely every week. Available at: https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/news-releases/new-apa-poll-one-in-three-americans-feels-lonely-e (accessed April 1, 2025).

- Arain, M., M. Haque, L. Johal, P. Mathur, W. Nel, A. Rais, R. Sandhu, and S. Sharma. 2013. Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 9:449-461. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s39776.

- Arnett, J. J., R. Žukauskienė, and K. Sugimura. 2014. The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 1(7):569-576. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(14)00080-7.

- Aronica, K., E. Crawford, Licherdell E., and J. Onoh. 2019. Models and mechanisms of public health: Social ecological model. Available at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-buffalo-environmentalhealth/part/chapter-3/ (accessed March 31, 2025).

- Bazron, B. J. 2023. Mental health and substance use report on expenditures and services: MHEASURES annual report fiscal year 2023. Washington, DC: Department of Behavioral Health

- Butler, A. 2020. Creating safer spaces for LGBTQ youth: A toolkit for education, healthcare, and community-based organizations. Washington, DC: Advocates for Youth.

- Campus Mental Health. n.d. Stepped care approach. Available at: https://campusmentalhealth.ca/toolkits/campus-community-connection/models-frameworks/stepped-care-model/ (accessed April 1, 2025).

- Cantor, D., B. Fisher, S. Chibnall, S. Harps, R. Townsend, G. Thomas, H. Lee, V. Kranz, R. Herbison, and K. Madden. 2020. Report on the AAU campus climate survey on sexual assault and misconduct. Washington, DC:

- CCRC (Community College Research Center). n.d. Community college FAQs. Available at: https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/community-college-faqs.html (accessed March 31, 2025).

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2021. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): Preventing early trauma to improve adult health. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/aces/index.html (accessed March 31, 2025).

- Chang, C. J., B. A. Feinstein, S. Meanley, D. D. Flores, and R. J. Watson. 2021. The role of LGBTQ identity pride in the associations among discrimination, social support, and depression in a sample of LGBTQ adolescents. Annals of LGBTQ Public and Population Health (3):203-219. https://doi.org/10.1891/LGBTQ-2021-0020.

- Cheng, C., and O. V. Ebrahimi. 2023. Gamification: A novel approach to mental health promotion. Current Psychiatry Reports 25(11):577–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-023-01453-5.

- Clark, B. C., and M. Taylor. 2021. 2021 Fall term Pulse Point survey of college and university presidents, part II.Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

- Coffino, J. A., S. P. Spoor, R. D. Drach, and J. M. Hormes. 2021. Food insecurity among graduate students: Prevalence and association with depression, anxiety and stress. Public Health Nutrition 24(7):1889–1894. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980020002001.

- Cohen Veterans Network, and NCBH (National Council for Behavioral Health). 2018. America’s mental health 2018. Available at: https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Research-Summary-10–10–2018.pdf (accessed April 1, 2025).

- Colizzi, M., A. Lasalvia, and M. Ruggeri. 2020. Prevention and early intervention in youth mental health: Is it time for a multidisciplinary and trans-diagnostic model for care? International Journal of Mental Health Systems 14(1):23.

- Collinson, B., and D. Best. 2019. Promoting recovery from substance misuse through engagement with community assets: Asset based community engagement. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment 13:1178221819876575.

- Compton, W. M., J. Gfroerer, K. P. Conway, and M. S. Finger. 2014. Unemployment and substance outcomes in the United States 2002–2010. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 142:350-353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.012.

- Cuccia, A. 2023. DC has 420 housing vouchers for youth leaving foster care. Why isn’t it using them all? Available at: https://streetsensemedia.org/article/dc-housing-vouchers-youth-leaving-foster-care/ (accessed April 7 2025).

- Davis, J. P., T. M. Dumas, and B. W. Roberts. 2018. Adverse childhood experiences and development in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood 6(4):223–234.

- Davis, M., A. J. Sheidow, M. McCart, and K. Zajac. 2012. Prevalence and impact of substance use among emerging adults with serious mental health conditions. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 35(3):235-243. https://doi.org/10.2975/35.3.2012.235.243.

- DC CFSA (Child and Family Services Agency). n.d. Placement of children in foster care. Available at: https://cfsadashboard.dc.gov/page/placement-children-foster-care (accessed April 8, 2025).

- DC Front Runners. n.d. About us. Available at: https://dcfrontrunners.org/about/ (accessed April 1, 2025).

- DC Public Library. n.d. About us. Available at: https://www.dclibrary.org/about-us?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjwna6_BhCbARIsALId2Z3eLNCESFpOFVYTVDWFM6hYtVG1XQJpPOjxXnvMRq5hDlla6vBuEMAaAuY6EALw_wcB (accessed April 1, 2025).

- gov. n.d.a. Department of Behavioral Health. Available at: https://dbh.dc.gov/page/about-dbh (accessed April 1, 2025).

- gov. n.d.b. What’s my Ward? Available at: https://planning.dc.gov/whatsmyward (accessed April 1, 2025).

- DCPA (District of Columbia Psychological Association). n.d. Our mission. Available at: https://www.dcpsychology.org/who-we-are (accessed April 1, 2025).

- Deal, T., A. Cienfuegos-Silvera, and L. E. Wylie. 2022. Meeting the needs of emerging adults in the justice system. Williamsburg, VA: National Center for State Courts.

- DiFulvio, G. T., S. A. Linowski, J. S. Mazziotti, and E. Puleo. 2012. Effectiveness of the brief alcohol and screening intervention for college students (BASICS) program with a mandated population. Journal of American College Health 60(4):269-280. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2011.599352.

- Drug Free Youth DC. n.d. Home. Available at: https://drugfreeyouthdc.com/ (accessed April 1, 2025).

- Ekers, D., L. Webster, A. Van Straten, P. Cuijpers, D. Richards, and S. Gilbody. 2014. Behavioural activation for depression; An update of meta-analysis of effectiveness and sub group analysis. PLOS ONE 9(6):e100100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100100.

- FH Faunteroy Center & Resilience Incubator. n.d. About. Available at: https://faunteroycenter.org/about-us/ (accessed April 1, 2025).

- FirstGen Forward. n.d.a. Are you a first-generation student? About the Center for First-Generation Students. Available at: https://firstgen.naspa.org/why-first-gen/students/are-you-a-first-generation-student#:~:text=Being%20a%20first%2Dgen%20student%20means%20that%20your%20parent(s,family%20member%E2%80%99s%20level%20of%20education (accessed April 1, 2025).

- FirstGen Forward. n.d.b. First year experience, persistence, and attainment of first-generation college students. Available at: https://firstgen.naspa.org/files/dmfile/FactSheet-02.pdf (accessed April 1, 2025).

- FirstGen Forward. n.d.c. FirstGen Forward network. Available at: https://www.firstgenforward.org/our-initiatives/firstgen-forward-network (accessed April 1, 2025).

- Fish, J. N., and C. Exten. 2020. Sexual orientation differences in alcohol use disorder across the adult life course. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 59(3):428-436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.04.012.

- Flaherty, C. 2023. Reputation, affordability, location and… mental health? Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/student-success/health-wellness/2023/06/06/how-prospective-students-value-colleges-mental (accessed March 31, 2025).

- Gardner, B., P. Lally, and J. Wardle. 2012. Making health habitual: The psychology of “habit-formation” and general practice. British Journal of General Practice 62(605):664-666. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp12x659466.

- Halfon, N., C. Forrest, R. Lerner, and E. Faustman. 2018. Handbook of Life Course Health Development. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Hamilton, I., and V. Beagle. 2023. 56% of all undergraduates are first-generation college students. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/advisor/education/online-colleges/first-generation-college-students-by-state/ (accessed August 19, 2025)

- Hanson, M. 2024. Pell Grant Statistics. Available at: https://educationdata.org/pell-grant-statistics (accessed April 1, 2025).

- Hanson, M. 2025. College enrollment & student demographic statistics. Available at: https://educationdata.org/college-enrollment-statistics (accessed April 1, 2025).

- Hayden, C. n.d. About the library. Available at: https://www.loc.gov/about/ (accessed April 2025).

- Hill, F. 2024. 20-Somethings are in trouble. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2024/08/young-adult-mental-health-crisis/679601/ (accessed April 1, 2025).

- HMN (Healthy Minds Network). 2023. The healthy minds study: 2022–2023 data report. The Healthy Minds Network. Availabe at: https://healthymindsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/HMS_National-Report-2022-2023_full.pdf (accessed Month Day Year).

- Horn, L., and S. Nevill. 2006. Profile of undergraduates in U.S. postsecondary education institutions: 2003–04 with a special analysis of community college students. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.