Charlee M. Alexander

Jessica Castner

Steve Singer

Cynthia Daisy Smith

Carol A. Bernstein

David B. Hoyt

T. Anh Tran

Pamela Cipriano

COVID-19 Working Group.

Introduction

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the general public may have been unaware of the growing health care worker burnout crisis. However, during the pandemic, it was difficult to miss media reports of increasing levels of burnout, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among health care professionals caring for seriously ill patients infected with a novel disease (Gregorio, 2020; Farrar, 2021). This media coverage, tied with reporting about the “great resignation” has led to increased knowledge about the challenges health care workers faced during the pandemic and continue to face today (Yong, 2021).

Patients, not only with COVID-19 but with any health condition, acutely realized that health care worker burnout affects everyone because the well-being of health care workers is “essential for safe, high-quality patient care.” (NAM, n.d.). Furthermore, the public trust that their health care will be available, safe, and of high quality. This mutual agreement and understanding—a social contract—in which patients grant trust in health care workers to fulfill their roles as healers was disrupted during the pandemic (NAM, 2024).

Alarming rates of health care worker burnout were present throughout the workforce prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, driven largely by an imbalance between job demands and job resources (NASEM, 2019). Burnout and unsupported well-being in health care workers can result in higher staff turnover, lower morale and productivity, and increased labor costs as health care organizations turn to contract staffing to address staffing shortages and maintain critical services (AHA, 2022; Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022; Galvin, 2022; Nuber, 2022). However, many health care workers experienced the occupational exposures inherent with in-person patient care during the pandemic as well as their own or loved ones’ actual and potential COVID-19 infection and recovery, giving rise to new levels of stress and burnout. Health care workers’ experiences of moral injury, which can occur in response to acting or witnessing behaviors that go against an individual’s values and moral beliefs, and personal threats to safety and well-being were widespread, with negative consequences for mental health and burnout (Chirico et.al, 2021; Nieuwsma et al., 2022; Noguchi, 2021; Norman & Maguen, 2020).

Since the recommendations were set forth in the 2019 consensus study, Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being, a number of publications have called for urgent action to improve health care worker well-being in light of the pandemic including Addressing Health Worker Burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce and the National Academy of Medicine’s (NAM) Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience’s National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being (NAM, 2024; NASEM, 2019; Office of the Surgeon General, 2022). Although action has been taken, it has not been at the scale or speed needed to address this mounting crisis and the pandemic has only exacerbated this urgency further. There is an immediate need to prioritize well-being, secure and allocate resources to support innovative approaches to reduce burnout, and scale and accelerate effective learning and improvement strategies for both near- term crisis relief and for long-term sustainable change (Mantri et al., 2020; Meese et al., 2021). The rationale for these interventions was also well documented in the 2019 consensus study. In short, the risks to quality and safety of care, mounting pressures of workload burden on clinicians, more frequent moral and ethical dilemmas, technology challenges, misalignment of personal and work time and diminished meaning in work all threatened the clinical work and learning environments. These harmful effects were only exacerbated by the pandemic.

This paper and its authors intend to make the case against “active forgetting” of the COVID-19 pandemic or “going back to normal” as the world appears to have adapted to an endemic state of the disease. Just as there are numerous lessons to be learned from COVID-19 to prepare for future pandemics, health care leaders must absorb the lessons COVID-19 has delivered on the critical nature of the nation’s health care workforce, the existing precarity of their collective well-being, and how critical it is to care for those who care for us. Health care leaders must seize this moment to enact courageous, comprehensive, and innovative changes to pre-pandemic and “business as usual” conditions that support the well-being of and actively reduce burnout among the nation’s health care workforce. Health care workers are still suffering—there is no time to waste.

Note from the Authors

Significant time has transpired from the initial conception of this paper and review of the literature. This paper utilizes resources that were available early on that accurately describe the effects of the pandemic but only reflect work in progress at the time to combat burnout and restore well-being. Fortunately, there has been positive progress in addressing the effects of the pandemic and pursuing strategies at organization and national levels to reorient our health systems to value well- being and invest in long-term solutions. An update on progress appears at the end of the paper as an Epilogue.

Aims of the Paper

This paper was written to:

- review the impact of COVID-19 on health care workers and their well-being;

- define challenges and changes needed to create an organizational culture of well-being;

- illustrate lessons learned that inform how to best cultivate a culture of well-being in health care organizations; and

- call health care leaders to actions that resist “active forgetting” for the sake of “moving on” and to pursue strategic actions for recovery that prioritize health care worker well-being in health care organizations now and in the

To identify lessons learned, information was obtained for the time spanning from January 2020 through March 2022. Due to the rapidly changing nature of the pandemic, and acknowledging the time lag between completion of studies and their publication in peer-reviewed journals, relying solely on peer-reviewed literature would not allow for an up-to-date assessment of what health care organizations were doing to address the burnout crisis. The authors expanded their information-gathering efforts by incorporating a scoping review of contemporary press releases and news media databases, questionnaire responses from frontline health care workers about their experiences during the first year of COVID-19, and insights gathered from a convening of the NAM action collaborative in March 2022 (see Appendix A). The questionnaire targeted any health care professional in the NAM action collaborative network to gather qualitative responses on their stress and burnout during COVID-19, as well as creative solutions that their employers have implemented in response to COVID-19 that they would like to see continue. Compelling examples representing role type, career stage, and geographic health setting were selected to expound upon their responses during an April 2021 NAM listening session with the Surgeon General.

Impact of COVID-19 on Health Care Workers and Their Well-Being

Burnout is a workplace syndrome characterized by high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization or cynicism, and a low sense of personal accomplishment from work (NASEM, 2019). Many work system factors (i.e., job demands and resources) contribute to the risk of burnout or have a positive effect on well-being (NASEM, 2019). Among health care workers, burnout is associated with job demands such as workload, time pressure, and administrative processes that detract from patient care. Among health care learners, burnout is related to inadequate support, supervisor and peer behaviors, and lack of autonomy, among other stressors (NASEM, 2019). Burnout is often defined as beginning when job demands exceed job resources; therefore, all aspects of the health care system and environment that impact job demands or job resources can contribute to exacerbating burnout or supporting well-being.

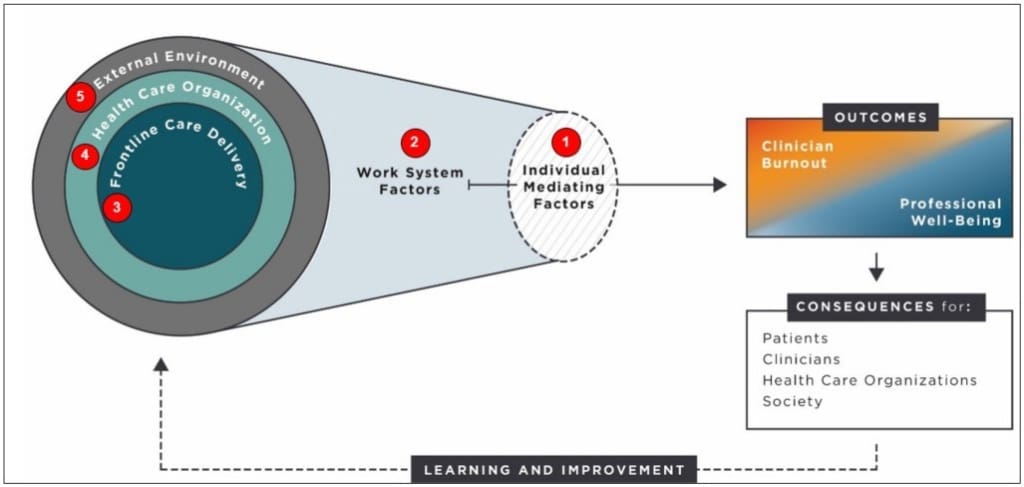

The 2019 consensus study “Taking Action

Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being” developed a systems model of health care worker well-being that remains relevant and important to understanding the interplay among:

- individual mediating factors,

- work system factors,

- frontline care delivery,

- health care organizations and systems, and

- the external environment

that can lead to burnout or support well-being (see Figure 1). The authors of this paper further elaborate on this systems model to detail how COVID-19 impacted all five interactive elements outlined above by synthesizing peer-reviewed literature, gray literature, and qualitative data from frontline health care workers. Understanding how COVID-19 changed, complicated, and exacerbated existing relationships and tensions within the health care environment is critical in order to create and implement effective solutions to support health care worker well-being.

The authors have listed the COVID-19 effects on the factors and levels described in the model based on the literature and insights from frontline health care workers gleaned from surveys and an NAM listening session with the Surgeon General. Understanding these effects can help health care leaders understand what frontline workers experienced during COVID-19 and especially how these experiences contributed to, compounded upon, and led to increased levels of burnout and reduced well-being.

1. Individual Mediating Factors

Individual mediating factors, like personality, life experiences, and personal resilience are the lens through which all other aspects of the health care environment are experienced and synthesized. Below are some of the personal and individual experiences shared by frontline health care workers. Health care workers shared their needs during COVID-19, which mirrored the sources of anxiety summarized by Shanafelt, et al. (2020) as “hear me, protect me, prepare me, support me, and care for me.”

- Health care workers shared their ongoing fear of getting COVID-19, problems associated with the acute illness if it was contracted, and symptoms associated with post-acute COVID-19

- Health care workers’ personal relationships and social supports were eroded by a looming concern about isolation and quarantine as they continued interacting with other health care workers, patients, and families affected by COVID-19.

- Health care workers’ basic needs for rest, health, shelter, and food—exacerbated by COVID-19—demanded attention and investment from some organizations despite general lack of resources and uncertainty about the future.

FIGURE 1 | How COVID-19 Affects Health Care Worker Burnout and Professional Well-Being NOTE: Numbers in Figure 1 correspond to the descriptions in the following sections of this paper that detail how the effects of COVID-19 altered the presence and impact of individual and work system factors at different levels of the system and thereby affected health care worker burnout and well-being. SOURCE: Adapted from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019. Taking action against clinician burnout: a systems approach to professional well-being. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25521.

2. Work System Factors

Work system factors include both job demands and job resources. Their impact, funneled through the individual mediating factors, will influence the level of burnout for an individual health care worker. “Decisions made at the three levels of the system”— frontline care delivery, health care organizations and systems, and the external environment—“have an impact on the work factors” (NASEM, 2019).

Specific to COVID-19, due to the public health emergency, timelines for many routine activities, from hiring to point of care testing, were accelerated and priorities often abruptly shifted, straining individual care and taxing team-based care. Health care workers were often asked to provide care outside of their realm of expertise and work long, uninterrupted shifts due to the volume of seriously ill patients. Below are further insights from frontline health care workers about work system factors that influenced their burnout or well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Job Demands

- Staff shortages created increased workloads and longer shifts.

- Supply chain and equipment shortages threatened staff and patient safety.

- Crisis standards of care, which were decisions regarding allocation of scarce resources (beds, ventilators, oxygen, medications, ECMO, or other essential services led to moral distress) and when a person knows the ethically correct course of action but is prohibited from taking it affected health care workers throughout COVID-19 (AACN, n.d.).

- Caring for patients who were skeptical about COVID-19’s existence and best practices to avoid contracting the disease presented an additional, novel burden to health care workers. Health care workers specifically identified unvaccinated patients being admitted to hospitals during peak waves leading to an increased emotional and physical burden on the workforce that could likely have been avoided (AMA, 2022).

- External interventions that questioned the validity of COVID-19 and how to best care for patients who contracted the disease also excessively burdened health care workers. Front line clinicians specifically identified lawsuits challenging treatment plans as a job demand burden.

- Attempting to balance a high volume of acutely ill patients while also attempting to keep health care colleagues safe was another critical job demand specific to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Job Resources

- Inadequate, scarce, and uncomfortable personal protective equipment (PPE) contributed to an increase in health care worker burnout.

- Challenges to professional competence stemming from assignment of health care workers to unfamiliar clinical roles without appropriate training or orientation was another example of a job resource challenge specific to COVID-19.

- Continuous use of PPE and physical distancing to reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2 interfered with professional relationships and social support.

- During COVID-19, work–life integration challenges compounded and changed. Health care professionals specifically mentioned worrying about bringing COVID-19 home to family, loved ones, and roommates, resulting in some staying away from their normal living quarters.

- Last, disputes about if and how much hazard pay health care workers should receive complicated already fraught working conditions.

3. Frontline Care Delivery

Frontline care delivery (e.g., care team members, their activities, use of technologies, physical environment, and local organizational conditions) changed dramatically during COVID-19 compared to how frontline care delivery operated pre- pandemic. Below are personal reflections by health care workers on how COVID-19 affected some of the key contributors to burnout, as discussed by health care workers during the NAM listening session.

- Staff shortages varied significantly, some- times changing by the hour. Staff shortages put pressure on health care workers as they needed to take on additional patients and tasks to make up for the shortfall. The significant and continuous variation in staffing made any type of planning extremely challenging.

- Resource shortages were frequent and often unanticipated due to supply chain challenges across the globe. Critical supplies, PPE, and even oxygen were not readily available when already stressed staff needed them.

- Hospital unit types frequently changed to meet shifting needs and care for primarily COVID-19 patients initially and to adhere to constantly updated protocols as population care needs evolved through the course of the pandemic.

- The rapid introduction of telehealth and related technologies impacted health care professionals, positively and negatively (Zhang et al., 2020):

- Positive aspects: Increased access to care via telehealth services improved both patient and provider safety as routine exams and appointments could occur virtually, allowed some providers to work even while quarantined, and allowed educational activities to continue for some learners.

- Negative aspects: Some patients and providers found the switch to virtual care challenging and not all health care workers, learners, and patients could access these technologies, which exaggerated pre-existing disparities.

- All types of learners experienced disruptions in training and education as their teachers and instructors (and in some cases the learners themselves) pivoted to patient care, or health facilities limited access to learners to preserve PPE, or local policies drove community practices and services to shut down, eliminating clinical placement opportunities. Some disruption may have been partially mitigated by use of remote technologies; however, many teachers were novices in use of the technologies as were the students, thus the disruption still exacerbated burnout and reduced well-being for these learners.

The one positive aspect of COVID-19 that was highlighted in the NAM listening session was that health care workers’ jobs became much more meaningful; many formed new connections with colleagues and patients. This sense of meaning and increased connection partially mitigated burnout for some and promoted teamwork with sense of a shared mission.https://ccaoaccdcstg.wpengine.com/wp-admin

4. Health Systems

- Health systems, or care-providing entities, have their own organizational culture, payment and reward systems, resource management, and policies that shaped their COVID-19 response. Therefore, the impact that health systems had on individual health care workers varied from system to system, and the choices that some systems made impacted some workers positively and some negatively. Below is a summary of the major issues that impacted individual health care worker burnout highlighted from the listening session and the authors’ lived experiences.

- The pandemic clearly illustrated the short- comings and breakdown of just-in-time production, which many health systems relied on. Just-in-time production and procurement is a model that frees up supply storage space in health care delivery organizations by placing storage and distribution responsibilities with manufacturers, allowing organizations to dedicate space to patient-centered uses. However, the benefits realized with increased patient-focused space also meant that many health systems ran out of critical supplies quickly. This breakdown subsequently reshaped the supply chain, causing many organizations to rethink how they procured and purchased supplies.

- Health system leadership faced challenges in communicating rapidly changing COVID-19 guidelines issued from federal, state, and local authorities to the health workforce and in implementing these changes effectively.

- Challenges arose and evolved within the relationships between health systems and health care workers, including:

- Efforts, successes, and failures in striking the optimal balance between the need for productivity during the unprecedented pandemic surge and workers’ needs, including safety and protection from the virus, hazard pay, and support in changing roles among others.

- Loss of job security and income for some workers as services other than emergency, critical care and acute hospitalization were shut down and workers sent home.

- Mismatched values and incentives, and difficulties reconciling the two contributed to a lack of mutual trust between health system leadership and health care workers.

Despite the challenges listed above, some organizations were responsive and supportive of their workers’ needs in novel ways, which bolstered well-being and helped increase mutual trust. Health systems assisted health care workers in forming new high-functioning teams and processes that worked to reduce barriers to providing care and promoted transparency, trust, and well-being.

5. External Environment

A myriad of changing laws, regulations, standards, and requirements during the public health emergency affected decisions made by health systems, which then impacted frontline care delivery, work system factors, and individual health care workers. Individual health care workers were also directly and indirectly impacted by changes in American attitudes, behaviors, and norms as the pandemic progressed. Below are aspects of the external environment that contributed to health care worker burnout.

- The exodus of health care workers due to the stress of work in the pandemic, termed the “great resignation,” as well as expression of intent to leave one’s profession led to staffing shortages and feelings of abandonment by those who remained at their organizations (Carballo, 2022).

- Social and economic disparities, bias, and lack of diversity, equity, and inclusion affected encounters with patients and families, as well as with health system structures.

- The previously present social contract be- tween society and health care writ large was severely weakened or broke down during the pandemic. As trust and cooperation with the public declined, some demonized health care workers. Specific aspects of this breakdown that impacted health care workers included:

- Deepening of societal divisions such that the public doubted the validity of COVID- 19’s existence and efficacy of prevention measures, which fragmented responses to the pandemic and created “hot spots” that could have been avoided (Rosenthal et al., 2020).

- Patients and some colleagues viewed the values of individual freedom and social responsibility as conflicting rather than complementary, which made responding to the pandemic on the local, state, and federal levels much more challenging (Miller, 2020).

- Widespread mistrust of government authority and the scientific knowledge, including evidence-based methods for treating and preventing COVID-19 led some patients to question health care workers’ recommended treatment or insist on receiving treatment methods that were not evidence-based, which made providing care even more challenging (Nelson, 2020).

- Previously established relationships between patients and health care workers also broke down in many locations. Particularly challenging aspects of this breakdown included:

- The prevalence of medical misinformation. Many patients did not trust the care that health care professionals were providing, making health care workers’ jobs much more challenging, or had such a distrust of care that they delayed seeking it until their condition was too acute, leading to morbidity and mortality that could have been avoided (Nelson, 2020).

- Related to the prevalence of medical misinformation, trust and respect between the public and health care workers eroded significantly, which in some cases led to confrontations over diagnosis or care. These confrontations escalated significantly during COVID-19 and were a significant additive stressor.

- When confrontations like those described above escalated, they sometimes resulted in workplace violence and health care worker abuse (Ward et al., 2021). Violence and abuse stemmed from medical misinformation, lack of trust in health and health care, and racism, sexism, and xenophobia.

Some positive external environment developments during the pandemic included the eventual recognition of the challenges health care workers were facing and the creation of measures to address the pandemic, bias, social and economic injustice, and misinformation. The federal, state, and local governments also eventually relaxed pre-pandemic rules and regulations that reduced administrative burden and enabled telehealth to flourish, providing health care workers with opportunities to increase access for patients and more time to care for them.

Taking a broader view across the pandemic landscape, while multiple factors affect health care worker well-being and resilience, it must be acknowledged that some factors play a bigger role in driving distress and burnout than others in any given situation, role, or setting. Frontline health care worker accounts and the literature show that the drivers of distress evolved in step with the evolving stages of the pandemic. Early fear and uncertainty grew with the rapid rise of COVID-19 cases and deaths, followed by fatigue and mental duress as the pandemic continued (CDC, n.d.). Each wave of the pandemic forced health care systems to move through cycles of planning for surges: addressing shortages in medication, equipment, supplies, and staff; deprioritizing medical care that was not related to COVID-19; implementing crisis standards of care; and dealing with medical misinformation and declining public trust. Rapidly adapting to the unexpected became both the norm and expected from health care workers, with little acknowledgment of the burden that this adaptation added. Variations in community spread, initial limited availability of tests and vaccines, vaccine misinformation, and debates over public health policies added even more stressors to health care workers (Dooling et al., 2020; Kates et al., 2021).

The “Infodemic” of false, inaccurate, or misleading health information spread at unprecedented speed and scale during the pandemic and made people more likely to decline COVID-19 vaccination and reject public health measures (e.g., masking and physical distancing), while increasing the use and adoption of unproven and potentially dangerous treatments (Office of the Surgeon General, 2021). As hospitals filled with unvaccinated individuals who had contracted COVID-19, erosion of empathy for patients who declined vaccinations contributed to health care worker burnout. The infodemic became so damaging and widespread that the Surgeon General issued a report in 2021 confronting misinformation, stating that “health misinformation is a serious threat to public health” (Office of the Surgeon General, 2021).

COVID-19 also disproportionately impacted people of color, older individuals, and those with chronic illness or disabilities. Women, younger health care workers, and those with caregiving responsibilities had their work impacted at a higher rate than their peers (Dillon et al., 2022). These disparities in pandemic experiences were captured in a line from a poem by Damian Barr: “We are not all in the same boat. We are all in the same storm” (Barr, 2021; Noonan, 2020; Norful et al., 2021).

As illustrated above, health care worker burnout does not result from a simple calculus but is the product of multiple levels of decision making, systems function, and individual experience. No health care worker was impacted by the pandemic in the exact same manner as any other, which means that solutions to health care worker burnout need to be as adaptable as the health care workers themselves. However, the challenge of developing effective solutions should not and cannot detract from the urgency of this need. One specific location that could begin to impact health care worker well- being on the macro scale is changing the culture of health care to one that values well-being.

Re-orienting Health Care Toward a Culture of Well-Being

Health care has long held a culture of silence around discussing mental health, burnout, and well-being while expecting the workforce to simply accept the high-stress conditions. “Despite the prevalence of burnout, speaking up or seeking help to deal with work-related stress continues to be seen, especially within the culture of health care, as a sign of weakness or inability to ‘make it’ as a clinician” (Feist and Cipriano 2020). Even before COVID-19, clinicians feared speaking about mental health challenges, as pre-existing regulations could tie such disclosure to reduced hours or even the loss of one’s professional license.

It took a series of tragic events, perhaps most notably the death by suicide of emergency physician Dr. Lorna Breen on April 26, 2020, to truly grip the public’s focus on the culture of silence and the desperate need to dismantle it (Knoll et al., 2020). Since Dr. Breen’s death, and due significantly to advocacy from her family and the Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes Foundation, there has been a trend toward a more open dialogue to counteract the stigma and discrimination related to mental illness among health care workers and instead emphasize mental well-being. Since the advent of COVID-19, national organizations and individual health care workers have modeled vulnerability on social media and created online communities that destigmatize help- seeking behavior. Organizations are promoting access to free and low-cost counseling and peer- support, offering physician support lines, emotional PPE, and therapy aid, among other resources (American College of Physicians, n.d.).

In 2018, the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) issued a report on physician wellness and burnout that focused on licensing requirements, including whether licensure and renewal applications need to ask questions about “a physician applicant’s mental health, addiction, or substance use,” and offering “safe haven non- reporting” that would not penalize health care workers for seeking mental health support (FSMB, 2018). In May 2020, The Joint Commission urged health systems against inquiring about health care workers’ history of mental health conditions or treatment, stating that it is critical that health care workers feel free to access mental health resources (The Joint Commission, 2020). A 2021 study found that many state medical boards did not ask questions about mental health diagnoses or asked only about current impairment, suggesting improvement since previous reports (Saddawi- Konefka et al., 2021). However, only one state followed all the FSMB’s recommendations and many state regulatory agencies and hospital credentialing guidelines still require disclosures of substance use disorders or mental health diagnoses (Saddawi-Konefka et al., 2021). As of February 20, 2025, 34 medical licensure boards verified their licensure applications do not include intrusive mental health questions.

The Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act was signed into law on March 18, 2022 (The Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Protection Act, 2022). This bill provides $135 million over three years to train health care providers on suicide prevention and relevant mental health and behavioral health activities, as well as launches a national awareness campaign to address the stigmatization of mental health challenges and promote help-seeking and self-care among the health care workforce. The Biden administration dedicated $103 million in American Rescue Plan funding to address burnout and strengthen resiliency among health care workers (The White House, 2022). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will also continue grant programs to support health systems and providers in preventing burnout, relieving workplace stressors, administering stress first aid, and increasing access to high-quality mental health care for the frontline health care workforce.

In May 2022, the Office of the Surgeon General released Addressing Health Worker Burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce (Office of the Surgeon General, 2022). The advisory contains steps that different stakeholders can take to address health worker burnout. It calls for change in the systems, structures, and cultures that shape health care. Following on the Surgeon General’s advisory, the NAM released its National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being that provides specific goals and actions for improving the well-being of America’s health care workers. This plan builds on almost six years of collective work among NAM’s network of 200 organizations committed to reversing trends in health worker burnout (NAM, 2024).

Lessons Learned

The end goal of using the lessons learned in the pandemic is to grow well-being in the health workforce. Recognizing the personal threats to safety and well-being and moral injury expressed by frontline workers during the pandemic humanizes the experience and stresses the urgency of implementing sustainable strategies for immediate and long-term relief.

Lessons Learned from Frontline Health Care Workers

To honor the critical nature of hearing from frontline health care workers on how to best improve their well-being and protect against burnout, in April 2021, the NAM action collaborative asked their network partners of health, health care, and health care-related organizations to complete a questionnaire about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers’ personal and professional lives (NAM, 2021). The NAM action collaborative received 500 responses from health care communities across the United States, representing varied perspectives and experiences across the health professions, settings, career stages, ethnicities, and genders. Respondents also shared solutions implemented at their health care institutions to support the workforce one year into the pandemic. Key insights are listed in Boxes 1-3. As content in this section is captured from questionnaire responses, it is highly organization- specific and therefore may be difficult to generalize across organizations. Nonetheless, these insights provide a real-time snapshot of events from the perspective of those working on the front lines during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, what interventions worked for them and their colleagues, and what approaches fell short.

BOX 1 | Insights from Frontline Health Care Workers on Protecting Their Well-Being During COVID-19

What would you have wanted to happen to protect your well-being during COVID-19?

Goal: Expand team responsibilities and enhance communication for teamwork

- Provide leaders with training in communication and compassionate leadership.

Goal: Address schedule adjustments, hour restrictions, and time-banking challenges

- Provide different types of rotating schedule.

- Provide options for charting or documenting from home.

- Provide on-site child care or financial support for hospital employees.

Goal: Initiate process improvements and policy changes to assist health care workers in transitions from different stages of COVID-19

- Enact stiffer, consistent consequences for failure to follow safety mandates.

- Provide equal coverage and reimbursement rates for telehealth and in-person practice.

- Enact a COVID-19 leave policy that mandates that anyone who participated in a COVID-19 response should be allowed an additional 5 to 10 days off work to focus on self-care with no financial penalty.

- Increase transparency about the state of the organization and plans for operations, especially in times of great stress.

- Provide adequate access to and reimbursement for confidential and dignified mental health services.

- Ensure that health system leadership commits to providing financial and logistic support to staff (e.g., protected time); ensuring safer staffing ratios; and providing reasonable benefits to workers rather than investing in travelers.

SOURCE: NAM (National Academy of Medicine). 2021: Clinician burnout crisis in the era of COVID-19: insights from the frontlines of care. Available at: https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience- and-well-being/clinician-burnout-crisis-in-the-era-of-covid-19.

NOTE: Responses are summarized and organized thematically.

BOX 2 | Insights from Frontline Health Care Workers on What Worked in Their Organizations to Protect Well-Being During COVID-19

What worked in your organization?

Goal: Expand team responsibilities and enhance communication for teamwork

- Peer-support programs

- Daily leadership care rounds to check in on well-being of teams

- Town halls to address areas of concern

- Management being visible and truly helping when it is busy

- A women’s group that focused on supporting each other with some of the concerns regarding work–life integration

Goal: Address schedule adjustments, hour restrictions, and time-banking challenges

- The establishment of a system to automatically call patients with their COVID-19 test results, which saved thousands of hours of health care provider and staff time

- Mental health days—we were given a day every other week to take a break from work that didn’t count against sick days or vacation time

- Staggered schedules for on-campus work

Goal: Initiate process improvements and policy changes to assist health care workers in transitions from different stages of COVID-19

- Frequent and transparent communication about organizational capacity and updates about PPE, testing, and treatment

- Streamlining screening and testing of people prior to hospital entry

- Resources for doctors to get emergent or urgent mental health care

- Incentive bonus to full-time staff, due to challenges working with travel staff who make three times the hourly rate that full-time staff do

- Coordination of all the major assistance programs in the health system to help streamline access to basic needs, health promotion, wellness, employee assistance, peer support, spiritual care, and psychiatry

Goal: Implement technologies, including improvement of electronic health records

- Expanding telehealth capabilities

- Integration of immunization registries into the electronic health record, which automatically loads all vaccinations performed at pharmacies and mass-vaccination clinics and would save over a million clicks

- Investment in online resources for students and faculty to assist with virtual learning and engagement

SOURCE: NAM (National Academy of Medicine). 2021: Clinician Burnout Crisis in the Era of COVID-19: Insights from the Frontlines of Care. Available at: https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/clinician-burnout-crisis-in-the-era-of-covid-19.

NOTE: Responses are summarized and organized thematically.

BOX 3 | Insights from Frontline Health Care Workers on What Did Not Work in Their Organizations to Protect Well-Being During COVID-19

What did not work in your organization?

Goal: Expand team responsibilities and enhance communication for teamwork

- “My MD colleagues get the premium PPE and are able to opt out of direct care, ancillary staff can opt out, but nursing is there with the patient regardless of risk to ourselves.”

Goal: Address schedule adjustments, hour restrictions, and time-banking challenges

- “We are told that we need to take the time for our mental and physical well-being but are not provided the time to do so.”

Goal: Initiate process improvements and policy changes to assist health care workers in transitions from different stages of COVID-19

- “Instead of innovations for less stress during the pandemic, some of our administrative leaders have canceled our continuing medical education, halted our retirement contributions, and cut our clinical hours.”

- “The presence of family members is crucial in making decisions and recovery for patients. However, visitation restriction has significantly affected this process. The delays in decisions could really cost lives. Sometimes, it led to internal struggle and guilt.”

- “Hospital administrators seem to think putting up signs or giving out t-shirts makes people feel better. If it does, it’s only minimally so. What people need is to be heard, to have their concerns listened to.”

- “Absent leadership making uninformed decisions, fragile systems worsening, and doctors having full responsibility without control has been disastrous.”

- “Increased administrative burden related to COVID-19 (questionnaires before entering hospital, going to get tested weekly [required by one hospital, unpaid time]), extra documentation to admit patients.”

Goal: Implement technologies, including improvement of electronic health records

- “We are never able to disconnect from work.”

- “Being a frontline worker with no telemedicine opportunities available in my specific workplace, I was forced to face the COVID-19 fears and uncertainty early-on.”

- “Virtual meetings are all the same work and none of the fun of in person meetings—they are draining.

SOURCE: NAM (National Academy of Medicine). 2021: Clinician burnout crisis in the era of COVID-19: insights from the frontlines of care. Available at: https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience- and-well-being/clinician-burnout-crisis-in-the-era-of-covid-19.

NOTE: Responses are direct quotes from individuals.

In addition to the specific messages that health care workers shared, summarized in Boxes 1–3, below are the five most common messages that the respondents shared through the questionnaire.

- Health care workers experienced trauma and burnout specific to COVID-19 on top of existing large-scale system pressures and alarming stress levels among the health care

- The manifestation of burnout varied across health care workers, ranging from anxiety to moral distress to depression.

- Health care workers were not immune to the impacts of COVID-19 in their professional or personal lives and expressed frustrations with the dearth of opportunities to connect with their peers and thrive in their

- Efforts made by hospitals and other health systems to address burnout were generally viewed positively, but health care workers who didn’t feel supported expressed their desire for more interventions by their

- Health care workers expressed the need for burnout interventions implemented during COVID-19 to continue post-pandemic (NAM, 2021).

The authors wish to reinforce the critical nature of soliciting input and feedback from individual frontline health care workers before, during, and after implementing any approaches to support well-being or ameliorate burnout. As outlined in the first half of this paper, the pandemic and similar disaster-related stress has impacted health systems differently and as such, has impacted every individual health care worker differently as well. Frontline health care workers are the best source of immediate feedback and guidance on what is working and what isn’t, and health care leaders must consult them to ensure that interventions are producing the intended results. Approaches that have worked in one setting or organization may not work in another, and frontline health care workers will be able to explain why or why not. Even absent a disaster situation, health care leaders can obtain a wealth of information from those working within their systems and should make a consistent and continued habit of consulting them and understanding what is going well and what isn’t.

Lessons Learned Drawn from the Literature

The scope and scale of pandemic-related health care worker burnout and threats to well-being prompted bold and immediate actions, including the implementation of previously untested interventions across individual, group, organization, state, and federal levels. To identify evidence-based and promising solutions, the authors of this paper reviewed peer-reviewed and gray literature and integrated questionnaire responses from frontline health care workers about their experiences during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. The interventions listed below include those that have been written about in the literature, reported on in the news, or raised by individual health care workers. The following section also includes general categories of interventions that are worth additional research or investigation by health care systems and leaders.

While there were numerous self-care interventions that individuals implemented for themselves, the most effective interventions were implemented using quality improvement and/or research frameworks that were implemented within a work group or clinical unit (see Table 1) or utilized across broader, multi-unit organizational and systems levels (see Table 2). The NAM action collaborative was firm in its direction that individuals should not bear sole responsibility for burnout prevention or resilience and that these were shared between employers and the workforce. Interventions listed in the tables were effective in the specific institutions in which they were implemented. For the sake of space, the tables include only a short description of each intervention. Readers are encouraged to visit the listed sources for more detail on every intervention.

To retrieve contemporary system and organizational change interventions, the authors of this paper searched the gray literature through March 24, 2022 (see Appendix A, Box A-2). The interventions shown in Table 2 are organized into seven categories:

- Strategic change: aligning strategy, organizational leadership structure, human resource systems, organizational culture, organizational political processes, and technical functions with prioritized external environment influ- ences to ensure that the organization reflects the reality beyond its walls.

- Technology: key machine- or equipment- dependent techniques workers utilize.

- Structural: the underlying arrangement and function of all parts of the organization.

- Human resources management: stress management; wellness support; career mapping; employee development; perfor- mance management; service referral; benefit administration; reward systems; and other processes to recruit, diversify, select, train, retain, promote, exit, and/or

- Human process: implementing structured parliamentary or shared governance procedures, communications, decision making, group interactions, problem- solving, and democratic or informal group leadership

- Measurement systems: the formal indicators and metrics seen as the operational definition of organizational function, performance, goal, and outcome attainment.

- Culture: addressing the social and psycho- logical environment of the organization created by general or collective sum of norms, customs, values, beliefs, expectations, prac- tices, symbols, language patterns, behaviors, and achievements.

TABLE 1 | Most effective work group or clinical unit level interventions for pandemic health care worker well-being

| Intervention Function or Policy | Example Work Group or Clinical Unit Interventions | Examples of Scale to Broader Organization or External Environments |

|---|---|---|

Education |

Formal education on warning signs of compassion fatigue, how to identify it, and interventions to ameliorate compassion fatigue (Chaudoin, 2020 ; Emory, 2022) | Recorded webinar series discussing resources on uncertainty and compassion, being present in times of fear, physician mental health, and family relationships and coping in unprecedented times (WebMD, 2020; Ohio State Medical Association, 2021) |

Persuasion |

System of bidirectional communication between leaders and frontline workers to improve morale, provide sense of inclusion, and show appreciation (Kruskal and Shanafelt, 2021) | Affirmative text messages from state nurses’ association (SlickText, 2021) |

Incentivization |

Leadership provided free coffee cards and stickers as incentives for PPE adherence in the workplace (Moulton, 2020) | Provide emergency pay, child care, and elder care stipends for health care workers who work during the pandemic (Fresenius Medical Care North America, 2020)

Enable, incentivize, or nominate colleagues for Pathway to Excellence or Joy in Medicine recognition for health care worker well-being and empowerment during pandemic (Carson Tahoe Health, 2021; Geddes, 2021) |

Coercion |

Protests to employers in the form of sick-outs (similar to a 1-day informal labor strike) (American Pharmacists Association, 2021) | |

Training |

Group psychological or stress first aid training (Berg, 2020, 2021a)

Group stress recovery aid training (Berg, 2020) |

|

Restriction |

Service restriction to exclude international travelers from receiving treatment as effort to reduce virus exposure (Fresenius Medical Care North America, 2020) | Prohibit mandatory overtime (Thompson, 2022) |

Environmental restructuring (physical environment) |

Assurance of adequate PPE for unit (Hutton, 2020)

Design quiet rooms for staff to use during breaks (Chaudoin, 2020) |

Remodel buildings and structures to reduce employee COVID-19 risk (Hauer, 2021) |

Environmental restructuring (work task structure) |

Structured and supported breaks and timeouts immediately after particularly difficult patient care situation or patient death in group work processes (Chaudoin, 2020)

Rotating assignments to nurses of high-acuity patients so nurses can experience a break in continued high stress patient (Chaudoin, 2020) |

Commercial scheduling app for nurses to pick up last-minute shifts per diem at post-acute care facilities (Verma, 2021) |

Environmental restructuring (work social team functioning) |

Culture change to reduce profit focus and increase personnel, as well as decrease productivity expectations (Omahen, 2020) | Encourage and facilitate school, business, and community group donations of PPE (Moulton, 2020) |

Environmental restructuring (group composition) |

Pathways for retired health care workers to administer vaccines or otherwise reduce workloads for health care workers on duty (St. Catherine University, 2021) | Relax state licensing restrictions for individuals licensed outside of state to allow broader use of licensed personnel (Texas A&M University, 2020) |

Modeling |

Scholars of Wellness program, which embeds physician leaders to pilot wellness program using cohort model for leadership building, enhancing local capacity for wellness infrastructure, and support the cohort learning to work together (Berg, 2021b) | Support/implement the WorkHealthy Hospitals initiative (Oklahoma Hospital Association, n.d.) |

Enablement |

Grief wall or grief board on nursing unit with markings for each patient COVID-19 death (Munz, 2021)

Collective ways to share difficult experiences to assist in processing grief and expressing compassion fatigue such as discussions in staff meetings or support groups (Chaudoin, 2020) Group debriefing structure and support after any intense, or prolonged difficult situations (Chaudoin, 2020) Structured buddy system to pair new and experienced nurses to bridge knowledge gaps (Chaudoin, 2020) |

Provide reintegration psychosocial counseling for those returning to their home institution after traveling to treat at COVID-19 geographic hot spots or facilities (Polk, 2021)

Acknowledge anniversaries of collective traumatic experience dates (Berg, 2021a) |

Multi-component service provision |

Telehealth with adequate reimbursement (Hutton, 2020)

On-site health care worker mental health counseling (Chaudoin, 2020) First responder pet therapy dog visits to nursing unit staff (Berman, 2021) |

|

Multi-component Fiscal policy |

New business entities create increased access to additional financial capital via business restructuring, mergers, or acquisitions to support independent practices (Altais, 2020) | |

SOURCE: Created by the authors.

NOTE: Framework themes listed in the first column are based on the Behavior Change Wheel, a model that includes the factors that affect behaviors and the different types of interventions that may be used to change behavior (Michie et al., 2011).

TABLE 2 | Most effective organization and system-level interventions for pandemic health care worker well-being

| Type of Intervention | Practical Examples of Implementation |

|---|---|

| Strategic Change Interventions | Align system values with those of health care workers to promote positive work environments (Hartzband and Groopman, 2020). Utilize Department of Defense combat stress management organizational strategies to motivate health care workers during the pandemic (Gutierrez, 2020). Align worker wellness initiatives with principles of a trauma-informed approach to health care worker professional well-being (Berg, 2021a). Appoint a chief wellness officer to help establish a well-being program (Berg 2020; Ripp and Shanafelt, 2021). Use guiding principles to ensure compassionate leadership during the pandemic (Henry, 2021). Dedicate C-suite time and resources to health care worker well-being (Arespacochaga, 2021). Implement strategies in American Hospital Association’s Well-Being Playbooks and from the American Organization for Nursing Leadership resources to address burnout in different organizational settings. (Arespacochaga, 2021). Implement Pathway to Excellence or Joy in Medicine programs for health care worker well-being and empowerment during a pandemic (Carson Tahoe Health, 2021; Geddes, 2021). |

| Technology Interventions | Provide access to a “Thriving Together” platform with all internal employee resources for financial, emotional, social, physical, and professional growth bundled electronically (Christ, 2021). Implement telehealth format to enable safe health care, safe for patients and providers, minimize disruptions to health care during times when in-person care was risky for patients and providers, and maintain revenue stream of providers. (Certintell Inc., 2020). Integrate AI-powered tools into daily practice to reduce administrative and documentation burden, improve workflow, and support adaptive health care worker learning (McBride, 2020; Nuance Communications, Inc., 2020; Wellsheet, 2020). |

| Structural Interventions (work design, employee involvement, restructuring) | Hire additional health care workers to ensure adequate workforce reserves (Freeman, 2020). Hire additional mental health professionals to treat frontline health care workers (Prescott-Wieneke, 2020). Identify nonessential tasks that can be cut or eliminated from day-to-day health care worker workflow (Berg, 2020). Provide scheduling flexibility for all clinicians (Latimer, 2021). Create Caring for the Caregiver committee to identify best ways to support health care workers that are struggling with stress, potential burnout and mental health issues. (Moulton, 2020). |

| Human Resources Management Interventions (performance management, developing talent, managing workforce diversity and wellness) | Support health care worker needs during crisis reassignments outside of their usual expertise and expectations (Berg, 2020). Sustain and supplement existing well-being programs (Dzau et al., 2020). Implement policies and practices that maximize flexibility for workers with family caregiving responsibilities and work to eliminate workplace bias and discrimination associated with family caregiving (Stokes and Patterson, 2020). Proactively and consistently offer disaster mental health services (Morganstein and Ursano, 2020; Berg, 2021a). If a health care worker leaves the organization or profession, recognize their service and contribution, similar to recognizing the service of a combat veteran leaving the military (Kreiser et al., 2021). Provide access to Healthcare Providers First hotline so that health care workers can seek mental health anonymously (Volpintesta, 2020). Increase pay, use float pools, and partner with nursing schools to counter nursing shortages (American Organization for Nursing Leadership, 2021). |

| Human Process Interventions (communication, problem-solving, leadership style, interaction styles) | Implement universal anonymous and no reprisal reporting mechanisms to encourage continuous quality improvement (Dzau et al., 2020). Diversify health care worker voices (Latimer, 2021). Implement “Hear me” leadership rounds so that health care workers can express their stressors and needs directly to leaders (Berg, 2021a). Implement strong and transparent communications with daily updates to all employees, including daily incident command and daily divisional huddles. Convert administrative meetings to virtual format to allow flexibility to attend while offsite. Leaders should use standardized messaging, invite and address employee concerns, and provide weekly town halls to hear directly from individual health care workers (Henry, 2021). |

| Measurement Systems | Utilize and establish metrics of aggregate burnout and health care worker well-being to measure progress and degradation (Berg, 2021a). Eliminate meaningless metrics (Hartzband and Groopman, 2020). |

| Culture | Voluntary 6-week emotional health advocate training for a peer-support program to reduce stigma (Christ, 2021). Support and implement system-level culture change interventions with formal assessments and dedicated funding (Arespacochaga, 2021). |

SOURCE: Created by the authors.

In addition to the specific approaches outlined in Table 1 and Table 2, several more general interventions were also identified as critical to health care worker resilience and well-being during the pandemic. At the onset of the pandemic, when the health care workforce was faced with uncertainty and fear, the most common interventions to promote well-being were strategies designed to enhance communication between leadership and staff. A 2020 national survey of health care workers identified open and honest communication as an essential element of health care worker well-being during a crisis (Meese et al., 2021). Effective communications strategies included nightly virtual debriefing sessions for all staff in a department; frequent and transparent communication by leadership on organizational capacity; updates on issues such as PPE availability, testing, and treatment protocols in forums such as town halls; virtual debriefing sessions among health care workers on their day-to-day work; and daily leadership care rounds (Azizoddin et al., 2020).

Interventions that prioritized workplace safety and infection control were also numerous and effective. Some organizations provided housing to health care workers to quarantine after working so that they did not bring possible COVID-19 infections home to their families (Abramson, 2021). A survey of emergency department staff across ten organizations identified notable specific needs of health care workers, including access to PPE, on- site laundry services, fresh scrubs, on-site showers, and safe sleeping spaces (Kelker et al., 2021).

Once the immediate safety and workplace communication needs of health care workers were addressed, many interventions were implemented at the group or unit level using a quality improvement framework and rapidly scaled more broadly, often with national organization support (Berg, 2020). Important short-term responses included creating safe spaces for workers to share their feelings and experiences, as well as ensuring organizational leaders were taking time to listen to their rapidly evolving needs. Some organizations also started offering child care support for employees when day care and schools shut down.

Many organizations prioritized ongoing emotional support of frontline health care workers by providing access to virtual mental health services and/or well-trained peer support. The University of Minnesota implemented a psychological resilience intervention called Battle Buddies, which was founded on a peer-support model (Albott et al., 2020). Northwell Health established Team Lavender, an adaptation of Code Lavender, an interdisciplinary group of health care professionals dedicated to supporting staff during times of stress (Barden and Giammarinaro, 2021; Davidson et al., 2017). Columbia University expanded their pre- existing mental health support for clinicians by offering free formal mental health treatment and peer support groups (Dohrn et al., 2021). VITAL Worklife services in the state of Virginia created an app that provided peer coaching and free legal support to health care workers (VITAL Worklife, 2021). Commercial companies worked to become part of the solution as well, as many companies worked to stock advanced PPE and produce ways to sterilize N95 masks during the initial shortages (Radiation Shield Technologies, 2020).

Telehealth, telemedicine, and related technologies increased patient and health care worker safety during clinical encounters, while preserving access for many services, indirectly supporting the well-being of many health care workers. In addition to two-way real-time interactive audio–video encounters, audio-only telephone visits, asynchronous digital messaging, remote inter-professional consultations, and remote physiological monitoring were increasingly deployed to meet patient needs (Ye, 2021). The ability to care for many patients in their homes helped free up hospital beds for those with more urgent medical concerns and allowed patients to continue to access needed care. Related technologies improved access to health care worker and student mental health support and resulted in more efficient treatment algorithms. Education for many students and trainees was shifted into the virtual space to prevent interruptions to their programs (Baughman et al., 2021; Albott et al., 2020).

Last, health care workers often requested more frontline staff and adequate workforce capacity to provide high-quality patient care during COVID-19. In some instances, health systems created their own staffing agencies or technology applications to load balance existing staff (Christ, 2022). However, when these requests were instead met by embedding mental health professionals to treat the frontline staff rather than increasing the quantity of frontline staff, the organization risked focusing on the individual health care worker’s internal coping resources rather than addressing the true need for adequate clinical support. This case in particular reinforces the critical nature of listening to and responding to frontline health care workers’ needs, rather than assuming or interpreting what they “really need.”

| Main Intervention Focus | Practical Examples of Implementation |

|---|---|

| Individual Level | |

| Individual stress inoculation and coping: cognitive and emotional | Mindfulness (Anzalone, 2022; NLM, 2020a, 2021a, 2021b) Coaching program (NLM, 2020b, 2022a;) Stress first aid (NLM, 2022b) |

| Individual stress inoculation and coping: physical | Acupressure (NLM, 2020c) Progressive muscle relaxation (NLM, 2021c) Nutrition with mindfulness (NLM, 2020d) Prescription of psychedelics (NLM, 2021d) |

| Individual stress inoculation and coping: relational | Tools to identify and treat “stress injuries” (Swensen, 2022) |

| Individual biofeedback and self- monitoring | Fitness tracker feedback (NLM, 2021e) |

| Individual with Organizational Level | |

| Multi-level | CARE: Culture, Access, Resilience, Education (Mount Sinai Health System, 2022) |

| External Environment Level | |

| State level program evaluation | WHOLE intervention: Wellness, How One Lives Effectively chronic stress reduction program (Anderson, 2022) |

SOURCE: Created by the authors.

Evolving Interventions in Need of Further Research and Testing

The scope and scale of health care worker burnout and threats to well-being that emerged during COVID-19 created a need for immediate action that bypassed rigorous scientific review of the efficacy, effectiveness, reach, adoption, or maintenance of some innovative interventions. Additional financial resources have been allocated to develop and test interventions that support health care worker well- being as part of the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act, American Rescue Plan Act, state budget allocations, and private philanthropy. Understanding the efficacy of these interventions will ensure that health care workers are effectively supported now and into the future.

Table 3 includes examples of ongoing protocols to test interventions piloted during COVID-19. Most of these protocols focus on individual cognitive and emotional stress inoculation and coping techniques, followed by stress reduction strategies. The results of a search conducted by the authors of this manuscript included a mix of individual level, individual with organizational level, and external environment level protocols.

Calling Health Care Leaders to Action in Enabling and Enacting a Culture of Well- Being

As described earlier, changing the culture of health care to value and invest in well-being and reverse the culture of silence around mental health and help-seeking is critical in ensuring that health care workers’ well-being is supported on and off the job. Moreover, the explicit support and momentum that leaders can provide to generate systems changes are necessary to eliminate the culture of silence. Health care leaders are critical to ensuring that health care worker well-being and resilience is prioritized and valued. The following sections focus on concrete actions that health care leaders can take to propel needed changes to transform the health care culture to one that expressly values well-being.

Plan and Enact Solutions that Embrace Local Complexity

The annotated systems model in Figure 1 helps to explain and connect the interrelated factors that promote health care worker well-being. However, Figure 1 and recommendations from Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being cannot, on their face, be used as a detailed planning tool or reflect the context of a specific system or organization, including its culture, characteristics of its health care workforce, and details such as clinical settings and communities served. Leaders need to engage with their organizations, utilizing the principles of diversity, equity, inclusion, belonging, accessibility, and human-centered design to create context- specific plans for ameliorating the current crisis and ensuring well-being of the health workforce (Mackey, 1992; Ogilvy; 2005; Snowden and Boone, 2007; Holly et al., 2021; Liberating Structures, n.d.). Organizations can utilize lessons learned from the pandemic to tailor plans that consider the individual mediating factors, work system factors, as well as front line care delivery and health systems- level challenges unique to their environments, to recognize and address local complexity (Dima et al., 2021; Schulze et al., 2021). Designing interventions and taking action will also require factoring in the pace of external environmental changes that are enabling or stalling system changes.

Foster a Learning Culture

Curiosity to solve local problems fuels the com- munities at the heart of learning health systems where integration of experiences and data generate knowledge that is put into practice with the goal of continuous improvement (Guise et al., 2018). Instead of seeing the interventions reviewed in this paper as a menu of implementation options, leaders should envision them as an avenue to foster organizational learning. Leaders can take an active role in creating inclusive learning communities and an organizational learning culture that asks, “What is the problem we are trying to solve?” When these learning communities include many stakeholders within a health system—from the C-suite to the patient’s family—the learning community can determine how others’ actions informs what needs to be done and what is missing.

Pursuing that gap as a community is invigorating because it provides an intrinsic reward: discovering a solution that will help solve the problem. Leaders should engage levers for change within their organizations (e.g., patient-family partners, researchers, informatics, quality improvement, accredited continuing education, talent development, and performance management) to collaborate in this journey. Disseminating the resulting discoveries (i.e., what works for us) can then become the currency of true intra-organizational learning.

Center Joy and Meaning in Work as a Mission Imperative

Authentic leadership is a focal point for healing and building or re-building trust. Leaders’ core competencies—strategic thinking, leadership development, mentorship, tactical management, subject matter expertise, personal learning and growth, teaming and providing psychological safety, relationship building, communication excellence, and results orientation—present opportunities to engage the health care workforce in leadership. Leaders can create opportunities to include and engage all individuals at all levels of organizational decision making, from input, to planning, to creating strategy, to serving in leadership roles, and letting them know what they do matters.

Leaders can embrace innovation and creativity to re-center meaning and joy as the organizing principles for work (De Smet et al., 2021). A positive approach, coupled with tangible assets to support pursuit of improved well-being and reduced burnout in the work environment, is what can characterize effective leadership as health care workers and health care systems heal (Cox, 2020). Leaders need to believe they will find a way forward and need to be encouraged and rewarded for creating this attitude as their organization’s “north star.” This mindset of fostering well-being is needed not only to retain the current health care workforce, but also ensure that students and future recruits aspire to become health care professionals.

Further Advance a Research Agenda for Well-Being

Given the widespread intervention development and testing that occurred in response to pandemic needs, health care leaders, grant makers, and investigators should do more to design and fund rigorous studies to determine which interventions have the greatest impact on health care worker well-being. These studies should include details describing the setting, context, and supports that characterize the success for application by others. One option is to expand or fully optimize the Patient Centered-Outcomes Research Institute Healthcare Worker Exposure Response and Outcomes registry to research health care worker well-being (PCORI, n.d.). Another is to pursue opportunities within the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) research agenda to advance “total worker health,” aimed at improving overall health and well-being of the 21st century workforce (NIOSH, 2018). Additional suggestions include more widespread use of validated measures to assess well-being and burnout; using a shared taxonomy to describe findings; and implementing multi-level, organizational, and policy interventions. A forward-looking research agenda for pursuing innovative approaches to supporting health care worker well-being will be needed to demonstrate evidence for the effectiveness and applicability of the interventions described.

Continue to Center and Elevate Health Care Worker Well-Being Beyond COVID-19

The unprecedented character of the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted already fractured and stressed health care systems, organizations, and the workforce in ways that will forever alter health care. Leaders should encourage their colleagues to explore opportunities for fundamental redesigns of organizational and health care systems to center patient and health care worker well-being as the driver for what creates economic value, how success is measured, and how resources are distributed (WHO, 2020). Health care leaders should reframe the work environment as an engine for learning, growth, and fulfillment. In this future, the health care workplace will be a catalyst for the retention and recruitment of staff at all levels.

Limitations

This paper is intended to provide a review detailing the COVID-19 experience and interventions related to health care worker well-being from 2020 to early 2022. There was a considerable constraint on information gathering due to the delay between completing studies and projects and their publication. Nevertheless, it is an important chronicle of events, experiences, reactions, and solutions that create learning, understanding, and opportunities for growth and improvement to address the national crisis of burnout. This paper should be considered an early analysis of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care worker well-being, as the authors cannot predict perspectives that may develop as the effects of the pandemic further evolve and eventually recede. An additional limitation is the absence of methodological rigor in available resources.

Conclusion

Just as the COVID-19 virus continues to mutate, the features of the pandemic it wrought continue to change. This paper attempts to take a snapshot of health care worker burnout and challenges to professional well-being from the onset of the pandemic (early 2020) to when threats from COVID-19 were somewhat more predictable and manageable (late 2021 and early 2022).

The authors discourage active forgetting simply for the sake of moving on. Despite knowing that perspectives are likely to evolve, there are advantages to a near contemporary discussion of the challenges to health care worker well- being during this difficult period by highlighting important factors that may become forgotten or less recognized over time. What is currently lacking in perspective may be gained by immediacy. By ensuring the lessons learned through COVID-19 to date are not lost, the United States. can better address challenges to health care worker well- being—both as the pandemic further evolves, and when future serious public health emergencies arise. The pandemic prompted widespread priority, resources, innovation, and attention given to health care worker well-being and burnout. COVID-19 revealed that health care systems require major changes and ongoing investment to support health care worker well-being and meet society’s needs for effective, efficient, and compassionate health care. The pandemic presented opportunities to decrease administrative burdens, enhance team-based care, and make foundational changes in the culture of health care. To ensure lasting improvements in clinician well-being, these changes need to be sustained longitudinally as additional changes and innovations are tested, implemented, and improved upon.

In an insightful viewpoint published early in COVID-19, Shanafelt and colleagues remarked that “The best way to understand what health care professionals are most concerned about is to ask” (Shanafelt et al., 2020). Shanafelt and colleagues then outlined five requests from the health care workforce to their leadership, institutions, systems, and to the public: “hear me, protect me, prepare me, support me, and care for me,” which echoed many of the themes from the NAM listening session (Shanafelt et al., 2020). This simple but critical imperative—to ask those most impacted what they need, and then do it—can be superimposed on the conceptual model shown in Figure 1 to provide a deeper and more nuanced understanding of health care worker well-being and what can be done to support and improve it.

Health care systems must commit to ongoing investments in the health and well-being of their workers and learners. The well-being of personnel is foundational to a system’s ability to create resilient organizations and meet the quintuple aim of better care, better health, lower costs, better health care worker well-being, and health equity (Nundy et al., 2022).

People are an organization’s greatest asset and without human capital there is no health care. Knowing burnout existed before the pandemic, one must ask, how do health systems heal when their most valuable asset is suffering? Health care workers thrive in environments that ensure safety; do justice to qualities of equity, diversity, and inclusion; provide adequate resources; invest in workforce planning; and ensure a humanistic and ethical culture that values well-being. The physical and emotional sacrifices of so many in the health care workforce before, during, and after COVID-19 should be honored and used to guide sustained and effective solutions to not only deal with the current recovery from pandemic effects but address the sequelae of prolonged stress. The fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic requires active trauma recovery. Approaches to recovering from trauma describe multiple phases that consider the need for safety and stability, remembrance and grieving, and then reconnecting and re-establishing relationships (Herman, 1992). Individuals progress through recovery at different rates and healing relationships are often key in helping them recuperate after a traumatic event. Individual and organizational healing can also be shared experiences when recovering from shared trauma. Structuring well- being support for workers who freely opt to initiate or utilize individual-level interventions could be helpful but should not replace needed systems- level interventions and should not be exploited to divert attention from or mask the consequences of system-level shortcomings. A true commitment to well-being will require organizations to embed well- being as a value. Only through authentic leadership and commitment to values and resources will there be trust that health care systems are learning organizations committed to building a better future.

The high incidence of health care worker burnout and lack of well-being is a long-standing problem that was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. We need to strengthen and scale the innovation, priority, resources, and attention given to clinician well-being and burnout needed during the pandemic as opposed to active forgetting in an attempt to move on from this global tragedy. Change needs to be sustained and proactive. We can’t wait for the threat of another public health emergency to force further action. We can use the contemporary knowledge base presented in this paper and related resources to mobilize the appropriate use of available resources and plan for a more expanded and effective toolkit to address health care worker burnout in the future.