G20 High-Level Independent Panel on Financing Pandemic Preparedness and Response

COVID-19 upended societies and economies across the world, starkly demonstrating the need for all nations to invest in pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response (PPR). At the same time major drivers of pandemic risk are rising, and epidemics are occurring at higher frequency, with more severity, and with broader potential for global impact. The pandemic of tomorrow is not a theoretical risk – it can happen at any time. However, despite these rising risks, countries are still grossly under-invested in pandemic preparedness and response.

Now, amid rising social distrust and fragmentation many countries have begun scaling back official development assistance, causing significant disruptions to global health efforts. Against this backdrop, the G20 High Level Panel on Financing Pandemic Preparedness and Response has issued recommendations to accelerate financing for global health security preparedness and response. The panel’s report, Closing the Deal: Financing Our Security Against Pandemic Threats, sets out critical, actionable investments to expand access to medical countermeasures and strengthen the financing and mobilization of domestic resources for pandemic preparedness.

Learn More

Infographics

Five Key Recommendations

Minimum Annual Financing Benchmarks

About the Report

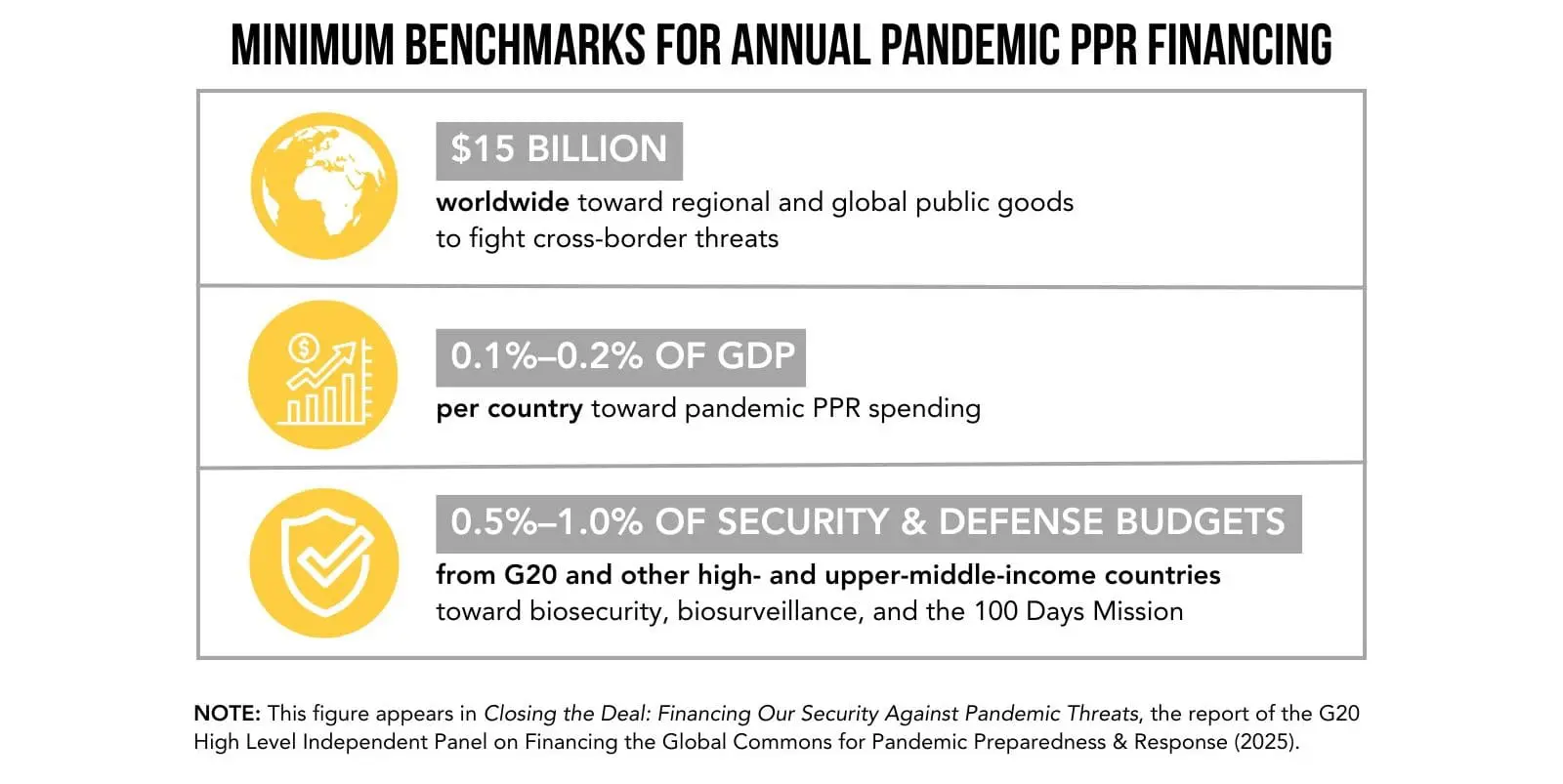

The G20 High Level Independent Panel sets minimum annual benchmarks for pandemic financing and urges governments to take action by or before the September 2026 United Nations High-Level Meeting on Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness, and Response.

Report Resources

Panel Members

- Victor Dzau (Co-Chair) | President, US National Academy of Medicine

- Jane Halton (Co-Chair) | Chair of the Board, CEPI

- Jean Kaseya (Co-Chair) | Director General, Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention

- Benedict Oramah (Co-Chair) | Former President and Chair of the Board, Afreximbank; and Chair of the African Medical Centers of Excellence

- John-Arne Røttingen (Co-Chair) | CEO, Wellcome Trust

- Seth Berkley | former CEO, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance; and Senior Advisor to the Brown Pandemic Center

- Chris Elias | President of Global Development Division, The Gates Foundation

- Amanda Glassman | Executive Advisor to the President, Inter-American Development Bank

- Rachel Glennerster | President, Center for Global Development

- Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw | Founder and Executive Chairperson, Biocon

- Syarifah Liza Munira | Senior Advisor, Joep Lange Institute Center for Health Diplomacy; and Former Director General of Health Policy, Ministry of Health, Indonesia

- David Miliband | President and CEO, International Rescue Committee

- Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala | Director General, World Trade Organization

- Patricia Reilly | Member of the Cabinet of European Union President Ursula von der Leyen

- Keizo Takemi | Former Member of the House of Councillors, Japan

- Elizabeth Cameron (Special Advisor) | Senior Advisor to the Brown Pandemic Center and Professor of the Practice of Health Services, Policy and Practice, Brown University School of Public Health

The G20 Italian Presidency originally convened the High-Level Panel on Financing the Global Commons for Pandemic Preparedness and Response in 2021. The Panel’s first report, A Global Deal for Our Pandemic Age, identified four major gaps in PPR and proposed nine solutions. Related resources include a high-level summary, public briefing, and press release.

Have Questions?

Get in Touch

The U.S. National Academy of Medicine serves as the HLIP Secretariat.

Contact: Melissa Laitner ([email protected]).

Copyright 2025 © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Powered by Social Driver.

Copyright 2025 © National Academy of Sciences.

All rights reserved.

Powered by Social Driver.