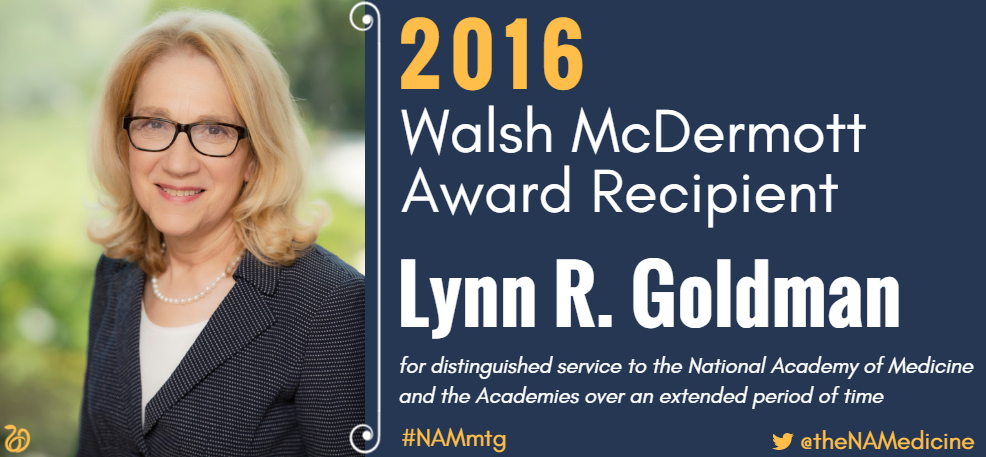

The National Academy of Medicine awards the Walsh McDermott Award annually to a National Academy of Medicine member for distinguished service to the National Academies over an extended period of time. Dr. Lynn Goldman, dean and professor of environmental and occupational health the Milken Institute School of Public Health at The George Washington University, received the 2016 award for her nearly-30-year history of volunteer service. In the following interview, Goldman discusses how she got her start in environmental health, why she chooses to volunteer with the National Academies, and why the perspective of people early in their careers is so crucial to advancing science and health.

How did you get your start in environmental health?

Goldman: I became interested in environmental and social determinants of health at a fairly early stage in my development. I volunteered and later worked for a free clinic while I was still an undergraduate student at the University of California, Berkeley. I was co-administrator for the clinic without even having a bachelor’s degree, so that tells you something! I loved the work but I came to feel that we were taking care of people and then, in a sense, plopping them right back into the conditions that were making them sick in the first place. I became passionate about moving upstream from the clinic and helping to prevent people from getting there to begin with.

When I applied for medical school, I started to realize that some of the things I wanted to do in my career weren’t, at the time, very mainstream. One of the people who interviewed me for medical school told me there was no such career as the career I ended up doing! That’s why I always advise young people to persevere with what they find interesting. I think young people can see the world in a different way–that they can be more attuned to where the world is going, as opposed to where it’s been.

You started volunteering with the National Academies early in your career. Why was that so important for you?

Goldman: My first involvement with the National Academies was when I was invited to give a presentation for a committee. They were looking for someone like me — an epidemiologist who worked in public health at the state level. I was completely unknown to them, and I guess I could have bombed, but I must not have, because they invited me back in 1989 to serve on my first committee. At that point, I had only been working in public health for four years and I was just within earshot of my residency. So I was very young. There weren’t very many people in my field at that time. There is some benefit to being early to get into a field, because then you can be the expert! Seriously, it’s very humbling for me that there are now thousands of people in my field, and I am by no means the leading light.

Getting involved with the National Academies early in my career was very helpful. Now, as a dean, when one of my faculty members gets invited to serve on a committee, it’s impressive in terms of what it adds to their record of service. It’s national service, it’s service with a very high impact level, and it’s impressive to hiring committees.

How do early-career scientists and scholars augment the work of the National Academies?

Goldman: I mentioned that I started out in a field that was very new, so I had a unique perspective. I think that’s true of a lot of young people today. They are working in areas where some of the more seasoned scientists may not be at the cutting edge. Young people are at the cutting edge. Even if they don’t have the same breadth of perspective as someone further along in their career, they can have far more depth, and, as I mentioned before, more appreciation for the state of the science and the state of the world today. They’re looking at it all with a fresh perspective.

Why have you continued to volunteer your time with the National Academies over so many years?

Goldman: I volunteer because of the impact National Academies work has on informing policy makers, informing society, moving the research agenda forward, and helping the government make difficult decisions. I’ve seen it over the course of my service — the work really does make a difference. Even though sometimes our work doesn’t have the immediate impact we might like it to have, over time the impact is enormous. I wish other countries had independent science bodies like the National Academies to advise them.

Tell us about one of your favorite National Academies projects. What kind of impact has it had?

Goldman: I chaired the committee that authored Secondhand Smoke Exposure and Cardiovascular Effects: Making Sense of the Evidence in 2009. It was a very difficult assignment because we had to assess whether smoking bans had reduced the incidence of heart attacks, and there weren’t many studies out there. But the committee did a beautiful job — I was very, very lucky. We were able to put all the data from many disciplines together and determine that yes, these bans were reducing acute coronary events, even among nonsmokers. I think the report provided powerful information not only for people in the United States but globally. I had the chance to go to China and present the report at the World Congress of Cardiology, as well as to a summit meeting of Chinese nongovernmental organizations. The Chinese took these findings very seriously and really got to work on trying to reduce smoking in China.

But we have a long way to go. We still have way too much smoking around the world, and, in countries like China and India, even smoking among cardiologists!

Do you think the general public understands the role of social determinants of health? Why isn’t there more of a demand for prevention among policy makers?

Goldman: On some levels they do and some levels they don’t. The general public does have a sense that there are things in the environment that threaten their health. Many of them understand that smoking and obesity and other lifestyle choices affect their health. Unfortunately, I don’t think we have the demand for prevention that we need. That goes for policy makers, too. We have an enormous demand for very expensive, very high-tech medical treatments. Once someone has cancer or another life-threatening disease, they’ll pay almost anything they can, or expect the government to provide payment, to fix it. Oftentimes we don’t see that same demand for prevention, even though it makes good sense economically, and for our health.

The Clean Air Act and the investment we’ve made in cleaning up the air we breathe has had enormous health benefits — and yet, when do you ever hear in political debates that government regulation can save money? We hear again and again the belief that regulation is bad for the economy. When we look at clean air, that’s certainly not the case. It’s had huge benefits for the economy. Somehow many of these issues have been cast in the wrong light. A lot of confusing information is provided to consumers and policy makers.

This takes me back to the National Academies and the importance of having a body that can speak the truth more clearly than the government can. These issues are difficult and extremely complex, and, understandably, people would like to find simple solutions. Yet it’s our job to unfold these issues in their full complexity and with complete honesty, regardless of the politics. We must speak truth to power, even when people don’t want to listen.

Tell us about some of your role models.

Goldman: Early in my career, I was often the only woman in the room. One thing that helped me tremendously is that I was lucky enough to work with men who were willing to serve as mentors and role models to me, a woman. That was so important.

John Harris, who ran the birth defects program in California, taught me how to hire good people and let them do their jobs. That has always helped me in everything I’ve done, whether it was working for an agency or running a research group. Alex Kelter, who was my division head when I first worked in the California State Health Department, had the ability to see straight through to the very nub of an issue and summarize it, and he taught me how to do that.

Dick Jackson, who’s also an NAM member, taught me to write. I did not emerge from my mother’s womb as a writer. I was always an incredibly awkward writer. One time in fourth grade we were assigned to write a story and read it in front of the class. I stood in front of the class with my paper, and I made something up on the spot because I was so unhappy with what I wrote. I often hear from people my own age that young people don’t know how to write anymore. But when did they ever know how to write? I didn’t know how to write! But you can learn it, even as an adult.

What does it mean to you to be a member of the National Academy of Medicine?

Goldman: It’s humbling. When I was inducted, I felt a little embarrassed. Hearing about someone who invented an artificial limb, I felt that nothing I’ve done is that important. But that’s why I volunteer. I can’t think of anything I’ve done for the National Academies where I haven’t found myself in a room full of people who are amazing, which I left with not only more knowledge about the subject area, but also a completely different appreciation for how to look at the question, how to work with a group, or how to interpret a set of findings. It takes you out of your normal peer group and puts you into a setting where there are just extraordinary people, often people from disciplines you might never interact with if you weren’t working on a National Academies project. A few years ago I was asked to chair a process to bring scientists from around the world together on short notice for a workshop to help inform measures to protect people from Ebola virus. I was stunned by the generosity and brilliance of people who were willing and able to provide so much scientific expertise on such short notice. It’s been an amazing experience.

Views expressed are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Medicine.

About the Walsh McDermott Award

The Walsh McDermott Medal is awarded to a member of the National Academy of Medicine in recognition of distinguished service to the NAM and to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine over an extended period of time. Service to the NAM and the Academies might include leadership roles as an officer, councilor, committee chair, committee member, reviewer, board member, fundraiser, or other such contributions that have enhanced and furthered the mission of the NAM. Service on committees of the Academies and jointly sponsored activities such as the Committee on Human Rights; the Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy; or the Government–University–Industry Research Roundtable shall be included as relevant contributions.